The catastrophic war in Syria seems to have gotten nearer to a tragic conclusion, but the end of this war may herald the beginning of other regional conflicts in the Middle East and Central Asia. What began as peaceful protests against the Assad regime’s dictatorial rule, soon evolved into a proxy war between Iran on the one hand, and Turkey, Saudi, and other Gulf countries on the other—and took on increasingly sectarian tones. As Syria’s war reaches an unstable end, a looming question for regional security is what will happen to these proxy forces, and in particular the foreign militias?

The catastrophic war in Syria seems to have gotten nearer to a tragic conclusion, but the end of this war may herald the beginning of other regional conflicts in the Middle East and Central Asia. What began as peaceful protests against the Assad regime’s dictatorial rule, soon evolved into a proxy war between Iran on the one hand, and Turkey, Saudi, and other Gulf countries on the other—and took on increasingly sectarian tones. As Syria’s war reaches an unstable end, a looming question for regional security is what will happen to these proxy forces, and in particular the foreign militias?

Although non-Syrian fighters have been documented on all sides of the conflict, Iran seems to support the largest numbers of foreign fighters, comprised of a diverse group of Shia proxies helping Tehran achieve its military goals in Syria. This is reflected in publicly available coverage of funeral services held in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon for Shia Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Pakistani nationals killed in combat in Syria.

The sources of this research include, but are not limited to, Ahl al-Beit News Agency’s (ABNA) coverage of funeral services held in Iran for Shia Afghan, Iranian and Pakistani nationals killed in combat in Syria, Arabi Press’ release of information about Lebanese Hezbollah fighters killed in combat in Syria, and Moassessa al-Shohada, Harakat al-Nujaba, and Kataeb Seyyed al-Shohada’s reporting on Shia Iraqi combat fatalities in Syria.

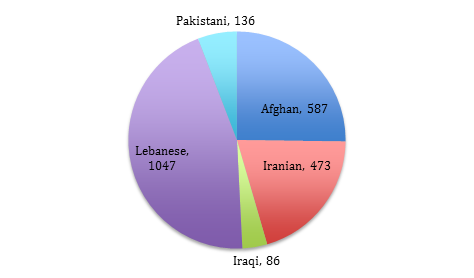

Between January 2012 to March 25, 2017, about 473 Iranian nationals were killed in combat in Syria. In the same time period, 587 Shia Afghan nationals, at the very least 86 Shia Iraqi nationals, 1047 Lebanese Hezbollah fighters, and 136 Shia Pakistani nationals were killed in combat in Syria. These actual death tools are likely slightly higher. Iran and its proxy forces do not report every casualty, and in fact try to cover up the actual number of deaths to prevent bad publicity about the military campaign and prevent opponents from estimating their actual forces.

Figure 1: A total 2329 Shia Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Lebanese and Pakistani nationals killed in combat in Syria January 2012 – March 25, 2017

The presence of “theological students” from the Persian Gulf countries in funeral processions in Iran, suggests that Shia nationals from Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and possibly Yemen are participating in combat in Syria alongside Iranian forces. However, this author has not identified those individuals, which may be due to their small numbers and the Islamic Republic’s attempts at keeping those fatalities secret.

Although it is hard to use a death toll to estimate the number of fighters a group has without knowing the actual death rate, these numbers show a high level of commitment and investment in the Syrian conflict. For example, in September 2013, when Hezbollah’s death toll was still estimated only in the low hundreds, analysts estimated that Hezbollah had between 2,000 and 4,000 fighters, experts, and reservists in Syria at a time. Since then, Hezbollah’s presence in Syria has only grown and become more essential as the Syrian regime’s forces have become more depleted.

Clearly, absent the Islamic Republic’s Shia proxies, Iran’s death toll in Syria would have been significantly higher. But apart from burden sharing and an attempt at limiting Iranian mortality in the Syrian conflict, what other motives were behind Iran’s deployment of non-Iranian Shia militias in Syria?

Iranian officials insist the government did not play a role in recruiting, organizing, training, arming or deploying non-Iranian Shia fighters in Syria. Instead, they claim that Afghan Fatemiyoun Division and the Pakistani Zeinabiyoun Brigade were established respectively in Afghanistan and Pakistan, after which a stream of “volunteers” flocked to Syria through Iran, to defend Shia shrines, and became “martyred defenders of the shrine” [shohada-ye modafe-e haram] upon death in combat.

Such claims, however, are contradicted by the fact that funeral services of Shia Afghan and Pakistani combat fatalities—which are well attended by their extended family—take place in Iran. This clearly suggest the “volunteers” immigrated to Iran prior to their enrollment in the militias. Hidden camera footage of an IRGC recruitment office in Mashhad in northeastern Iran, released by BBC Persian, provides further evidence of the Afghans and Pakistanis being recruited by the IRGC in Iran. Finally, defectors from the Fatemiyoun Division who fled to Turkey and Greece alongside Syrian refugees, in interviews with BBC Persian, disclose they received military training from the IRGC in Iran prior to their deployment in Syria by the civilian Iran registered Mahan Air.

The great degree of military coordination between the IRGC, Russian Air Force bombings in Syria, and the Lebanese and Iraqi fighters in Syria—a fact openly admitted by Rear Admiral Ali Shamkhani, Supreme National Security Council secretary—further points to the Islamic Republic’s active involvement in deploying these militias to Syria.

Iran supporting and deploying these Shia proxy militias helps it achieve its immediate goal of propping up the Syrian regime. In addition, even after the conflict, these multinational forces will continue to be an asset of the IRGC that it can use in future regional conflicts.

Such a force not only provides Tehran with a multinational Shia armed force capable of rapid deployment in the entire Middle East and Central Asia, but may also impact the IRGC’s willingness to engage in military adventurism. With the groundwork done—training the forces, organizing them, and building connections with indigenous networks—the IRGC will be able to ramp up faster and at a lower cost than any international efforts to contain it, putting the United States at an automatic disadvantage in future conflicts if it tries to stop Iran’s spreading influence.

Still worse, we may witness a replay of the 1980’s dynamics: as documented in Laurence Louër’s Transnational Shia Politics, following the revolution of 1979 and establishment of the Islamic Republic, many non-Iranian Shia moved to Tehran, climbed the political hierarchy of the revolutionary regime and played an instrumental role in shaping the Iranian government’s policy of “exporting the revolution” to the entire Middle East region. Similarly, the leadership of non-Iranian Shia militias of today—whose fighters are rewarded with permanent residency permit in Iran in return for their front duty in Syria—may evolve into effective lobby groups in Tehran advocating for Iranian support to Shia revolutionary movements in the Middle East and Central Asia. In this scenario, the militias will no longer merely be instruments of the Iranian state, but take advantage of the Islamic Republic to advance their own agendas in their home countries.

All this in turn bodes ill for future security dynamics in the home countries of those militias: once the war in Syria is over. The end of one war may plant the seeds of the next armed conflict and thereby perpetuate the vicious cycle of war in the Middle East and Central Asia.

Ali Alfoneh is senior nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Photo: Mourners carry the coffin of Amin Karimi, a member of Iranian Revolutionary Guards who was killed in Syria, during his funeral in Tehran October 28, 2015.REUTERS/Raheb Homavandi/TIMA