A region in flux, the Mediterranean of today–and tomorrow–faces an array of complex challenges. Demographic shifts, evolving political and security contexts, economic uncertainty, and climate change have created massive migration flows and regional instability, straining resources in southern Europe. These and other drivers of change have highlighted the increased importance of developing a transatlantic security strategy for the region.

In Mediterranean futures 2030, Scowcroft Center senior fellows Peter Engelke and Lisa Aronsson, and Scowcroft Center deputy director Magnus Nordenman, outline key drivers of change in the Mediterranean region, analyze plausible future scenarios, and provide strategy recommendations for the United States, Europe, and their Mediterranean partners to realize shared goals for the region moving forward. The report, an analysis out to the year 2030, balances the optimism of the 2011 Arab uprisings with a sober perspective brought about by the region’s more recent past, without losing sight of the potential for a better future. In identifying solid solutions to the region’s structural problems, this report is a vital handbook for policymakers seeking to make a long-term, positive difference to the region’s fortunes.

Table of contents

Drivers of change in the Mediterranean

Scenarios for the Mediterranean in 2030

Toward a strategy for the Mediterranean

Foreword

The security interests of the transatlantic community and the Mediterranean region have been closely intertwined for centuries, but never more so than today. The current turbulence along the southern rim of the Mediterranean has caused, among other things, state failure, a new wave of deadly terrorism with regional and global aspirations, and refugee flows into and through Europe on a scale not seen since the end of World War II. This all occurs within the context of the massive human suffering currently being experienced in the region itself.

The instability in the region has also had an impact far beyond its epicenter, with the British vote to leave the European Union clearly influenced by concerns that Europe has been unable to properly respond to the migrant crisis in its south. The Syrian civil war has also allowed Russia to re-insert itself into the Middle East, further complicating efforts to end conflicts and promote the spread of liberal values. Turkey is also under pressure from many directions as a result of the ever-changing security environment in the broader region, and is drifting away from its transatlantic partners whom it sees as unwilling to protect Ankara’s interests.

At the same time, European nations have experienced a string of high-profile terror attacks, inspired or directed by the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), a sprawling group that still holds significant territory in the region as of this writing. The rise and violence of ISIS have also affected American politics, where counter-terrorism is once again at the forefront of foreign policy discussions in Washington and a top priority of the incoming US administration.

Little of this was foreseen by decision makers on both sides of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean region just a few years ago. The strategic surprise has hampered the international response to the multifaceted crisis in the broader Middle East, has made coordination and cooperation among the many actors difficult, and has meant that the measures applied appear short-sighted and incremental. It has raised new questions about the capacity of established institutions like NATO and the European Union to adapt to meeting twenty-first-century challenges.

That is why this report is important. “Mediterranean Futures 2030: Toward a Transatlantic Security Strategy,” written by a team of the Atlantic Council’s experts, seeks to go beyond the crisis headlines of the day, discern the key drivers of strategic events and trends in the Mediterranean region, and devise a strategic framework for discussions about the future of the region.

This report brings much-needed intellectual grist for building a sustainable and long-term transatlantic strategy, in partnership with the nations of the region, for the Mediterranean basin in order to set it on a more peaceful, prosperous, and socially sustainable path. While the region is in turmoil today, and seems likely to remain turbulent for some time to come, it is not without its sources of strength, including energy resources, a population eager for change, a vibrant labor pool, and a strategic location as a crossroads of international trade and exchange. Mediterranean Futures 2030 will help the transatlantic policy community imagine that better future, while avoiding the many pitfalls that lie ahead.

Executive summary

The famous French historian Fernand Braudel emphasized the “longue” over the “courte durée” in his magisterial study of the Mediterranean in the age of Philip II. This report also takes the long view, examining the structural factors that help drive day-to-day events.

Touching three major regions—Europe, Africa, and the Middle East—the Mediterranean is in a vortex of change coming from all different directions. The Mediterranean region’s political, economic, physical, and cultural stability is increasingly in doubt. Without an understanding of the key drivers of change and their interaction, there is little possibility of developing a viable strategy for reversing the trends and achieving stability. This publication examines the needed roles of the United States, EU, and NATO to counter the slide towards instability and potential conflict.

A stable Mediterranean remains critical for Western security. Not tackling the underlying problems means that we will be fighting crisis after crisis without a chance of getting ahead of them. Foresight studies, such as this, are only valuable if they lead to strategic action.

Demography and destiny

For centuries, the Mediterranean has been a conduit for the exchange of peoples and their beliefs and talents as well as goods. The problem now is that there is a demographic imbalance with higher birth rates in the Middle East and Africa and little or no employment outlet for the youths in their societies. Moreover, in the Sahel and sub-Saharan Africa, climate change and water scarcity are undermining agricultural livelihoods and spurring migration.

Wealthier countries have always been magnets for those in search of better employment opportunities and superior education. The worsening civil war in Syria has unleashed a flood of refugees, many of whom have transited southern Europe in search of better job opportunities in Germany and Scandinavia. Further conflict in the Middle East cannot be ruled out even if a ceasefire in Syria is finally agreed.

The bottom line is that migratory pressures are here to stay. Migrants are potential assets for aging European countries if they can be economically integrated. Critical for stability on both sides of the Mediterranean will be ways to regulate flows, not to stifle them. It is to Europe’s long-term advantage if talented Africans and Middle Easterners better their education in its schools and universities. Europe, like other advanced economies, will need highly educated workers as skills gaps widen.

Africans, Middle Easterners, and their countries could benefit from studying and working in Europe. China, South Korea, and other rapidly developing countries have succeeded because they invested heavily in their workers, sending the brightest to the US and Europe for their education. Having economically successful countries around Europe’s borders is one of the best ways to ensure stability.

Climate change

Water scarcity and agricultural losses were root causes of the Syrian civil war. The current flow of migrants, especially from the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa, has intensified also due to systemic droughts and worsening agricultural conditions. Africa and parts of the Middle East need large-scale development assistance if they are to mitigate the worst impacts and avoid societal strife. There can be no true stability in the Mediterranean region without an antidote to the social and economic ravages of climate change.

Continuous political upheaval

Less than a decade ago, before the 2008 Great Recession, southern Europeans appeared to be on track to narrow the economic divide with richer northern Europeans. Now, however, southern Europeans have been thrust into an extended economic crisis in which youth unemployment has spiraled and growth has ground to a halt. Nine years later, an economic black cloud still hovers: debt levels remain high despite the belt-tightening, and much-needed structural reforms are unfinished. Trust in national governments and the EU is waning. As elsewhere in the West, populism and anti-establishment parties have been gaining, with publics tired of austerity.

In North Africa and the Middle East, this decade began optimistically with the Arab uprisings. The Middle East and North Africa seemed to be on the verge of following the rest of the world in replacing authoritarian rule with democracy. With Tunisia as the exception, the Middle East and North Africa have plunged into civil strife in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya; in Egypt and Turkey, there has been a reversion to authoritarianism.

The Mediterranean region looks far more unstable than just five–ten years ago. On the northern side, governments are on the defensive, unsure of whether or how to implement economic and social reform despite the need for it. Citizens are increasingly divided. On southern shores, middle classes have temporarily opted for security over civil rights, but governments do not have a recipe for long-term economic security for their citizens.

Oil price uncertainties

Many Middle Eastern and North African countries are oil producers and heavily reliant on the revenues from high oil prices to balance their books. For various reasons, the era of high oil prices seems to be coming to an end. Alternative non-fossil fuels are increasingly important in the energy mix. Oil producers need to be planning ahead. It is important, too, that the Gulf states, which are trying to reform their economies, succeed. Not only would they be in a position to continue to provide development assistance for the poorer countries in the region, but their failure would raise the risk of increased political and social instability throughout the whole region.

The importance of outsiders

Outside actors—such as the US, EU, NATO, Gulf states, China, and Russia—will play a pivotal role by their actions or inaction in preventing or helping to spread the risk of further instability. The report examines four scenarios—in all of them outside actors play key roles.

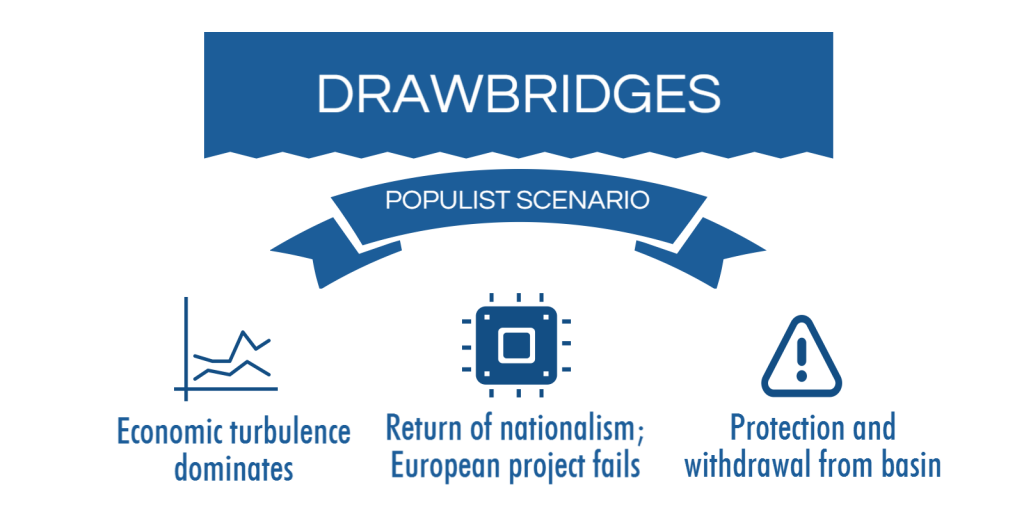

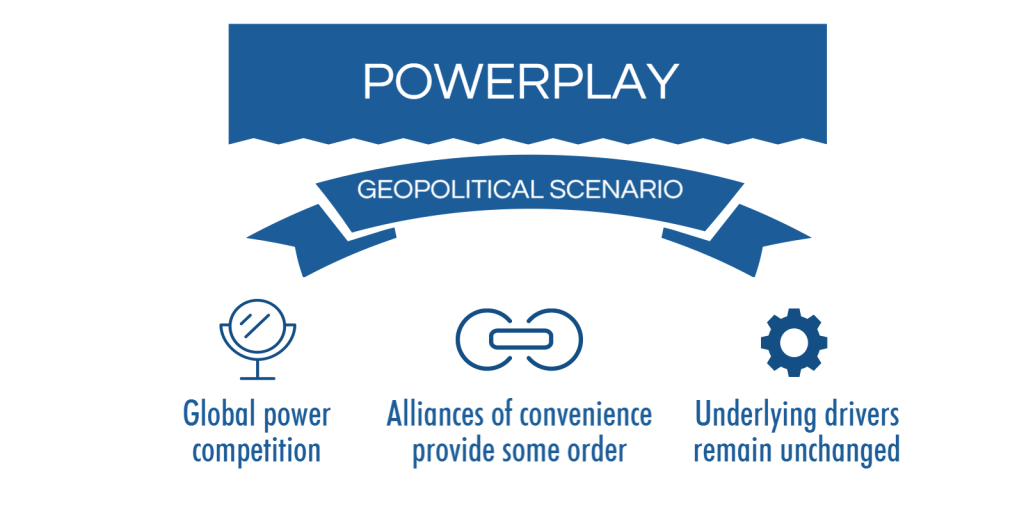

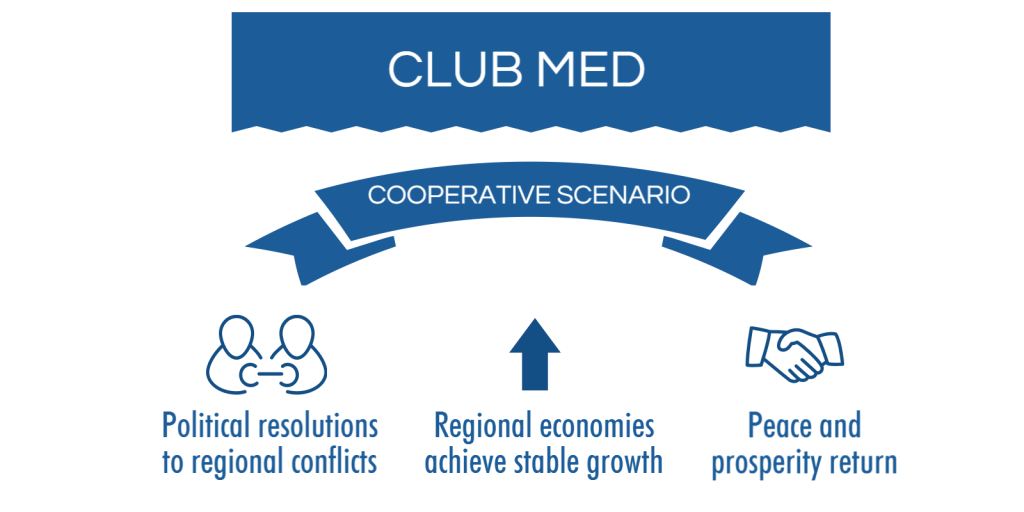

In Erosion, a weak EU and US make it hard to stabilize the region. In Drawbridges, a fortress-like Europe quarantines itself against any interaction with the south, weakening its own security in the long run. In Power Play, the great power rivalries do not have the interests of the region in mind, just their own advantage. But in the optimistic Club Med, there is an effort by outside powers to deal with security with the whole region.

In bringing about the fourth scenario, the report underlines that the Mediterranean is a key theater for NATO engagement, and operations there are of vital importance for the Alliance. NATO must be able to deter interstate conflict and defend Europe from traditional threats. It must protect its capacity to plan and carryout multilateral military interventions in the Mediterranean, and it must protect European and transatlantic sea power. To date, NATO’s political influence in the region has been limited by regional politics and by a lack of political will inside the Alliance for playing a big regional role.

The EU has to build a vision for itself as a political community that resonates for its people and connects with peoples on the other side of the Mediterranean. The EU is making progress on trade in goods, but more must be done on agriculture, services, and investment with key Mediterranean partner markets such as Algeria and Turkey. More needs to be done to bolster intra-Mediterranean trade. The EU should work toward enabling freer movement of legitimate forms of labor.

The United States needs to prioritize the Mediterranean as a coherent geographic entity and ensure there is a balance of power in the Mediterranean. As the Mediterranean has a huge north-south prosperity gap, the United States should pay more attention to development, supporting European development initiatives.

For other powers, such as China, the Mediterranean presents an economic opportunity. Centuries ago, there was trade between the Roman Empire and ancient China. China wants to recreate the land route, boosting direct trade and exchanges along it. Massive investment in ports, roads, and bridges would be two-way, increasing Chinese influence while boosting the Mediterranean economies. China is willing to make the investment, as demonstrated by its redevelopment of the Greek port of Piraeus, at a time when Greece’s economic fortunes are at a low ebb.

Peace and security are also unlikely without Russian support. With its links to Tehran as well as the Syrian regime, Moscow could play the spoiler role unless it is somehow included in any global effort to bring peace to the broader Mediterranean region.

Mediterranean Futures 2030: Toward A Transatlantic Security Strategy maps the underlying landscape of challenges and opportunities that have to be considered if any NATO or EU strategy is to be successful. So many of the trends point to continuing instability. Leaders both inside and beyond the Mediterranean region will have to step up to the plate if the negative trend lines are to be subverted and the abundance of human energy and ingenuity among its citizenry directed toward positive outlet, strengthening ties across the region. Outsiders also need to understand that peace elsewhere in Europe and Eurasia cannot be assured without there being a more secure Mediterranean. In identifying solid solutions to the region’s structural problems, this report is a vital handbook for policy makers wanting to make a long-term, positive difference to the region’s fortunes.

Introduction

The Mediterranean basin is in flux. After the Arab uprisings brought an initial wave of optimism that the basin’s fortunes were shifting for the better, the Mediterranean has since entered a period characterized more by conflict and uncertainty. Today, the Mediterranean is associated with instability and divisiveness rather than consistent progress toward shared goals.

This report, an analysis out to the year 2030, is the latest in a series of Mediterranean futures studies conducted since the Arab uprisings in 2011.1See, e.g., Eduard Soler I Lecha and Thanos Dokos, Mediterranean 2020: the Future of Mediterranean Security and Politics, Mediterranean Paper series, German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2011, http://www.gmfus.org/publications/mediterranean-2020-future-mediterranean-security-and-politics, World Economic Forum, Scenarios for the Mediterranean Region, Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2011, http://www.weforum.org/reports/scenarios-mediterranean-region; Mathew J. Burrows, Middle East 2020: Shaped by or Shaper of Global Trends?, Atlantic Council, 2014, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/middle-east-2020-shaped-by-or-shaper-of-global-trends. It attempts to balance the optimism of 2011 with a sober perspective brought about by the region’s more recent past, without losing sight of the potential for a better long-term future.2The report’s insights stem from a stakeholder-driven project over 2015-2016, which included roundtables in Washington, DC and individual interviews with experts and policymakers in Europe and Washington. It is intended to support efforts by the United States, Europe, and their Mediterranean partners to define a strategic framework for realizing shared goals to 2030. It identifies underlying drivers of change in the region, analyzes plausible scenarios, and provides strategy recommendations.

The future of the Mediterranean basin is relevant because of the basin’s continued centrality for transatlantic and global affairs. The Mediterranean remains central to the global economy, with its littoral states in Southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East possessing rich natural resources, extensive human capital, and presiding over several of the globe’s most important maritime passageways (the Suez Canal, the Bosphorus, and the Strait of Gibraltar). And, of course, these states have regional security interests that overlap and intersect with the interests of global powers such as the United States, Russia, China, and others.

State interests are only part of this story. Non-state actors move goods and people through and across the basin. Currently, refugees and migrants are fleeing violent conflict or economic insecurity, part of a large illicit economy that permeates the Mediterranean. Extremist groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) have emerged in the chaotic aftermath of war and in the political vacuum of state failure in Syria and Iraq. ISIS’s stubborn territorial grip has disrupted a fragile order in the broader Middle East, sending shock waves across the globe.

The Mediterranean is at once a coherent and bounded geographic space—a body of water—and it is also a broader and fluid community.

The European Union (EU) and its southern Mediterranean member states are trying to weather these same storms while coming to grips with their own challenges. The EU has a fine new Global Strategy, but to deliver on its aspirations for relevance and resilience, it must find solutions to its key challenges: monetary union, asylum and migration, stability on its frontiers, and a new framework for cooperation with the United Kingdom (UK) after Brexit. The EU’s Mediterranean states have their own challenges, ranging from sluggish economies to dealing with the influx of refugees, and the longstanding Cyprus dispute. The EU must also find creative ways to continue working constructively with regional partners around the basin. The political trajectories of Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, and Libya are uncertain, but their relationships with Europe will shape the region to 2030 and beyond.

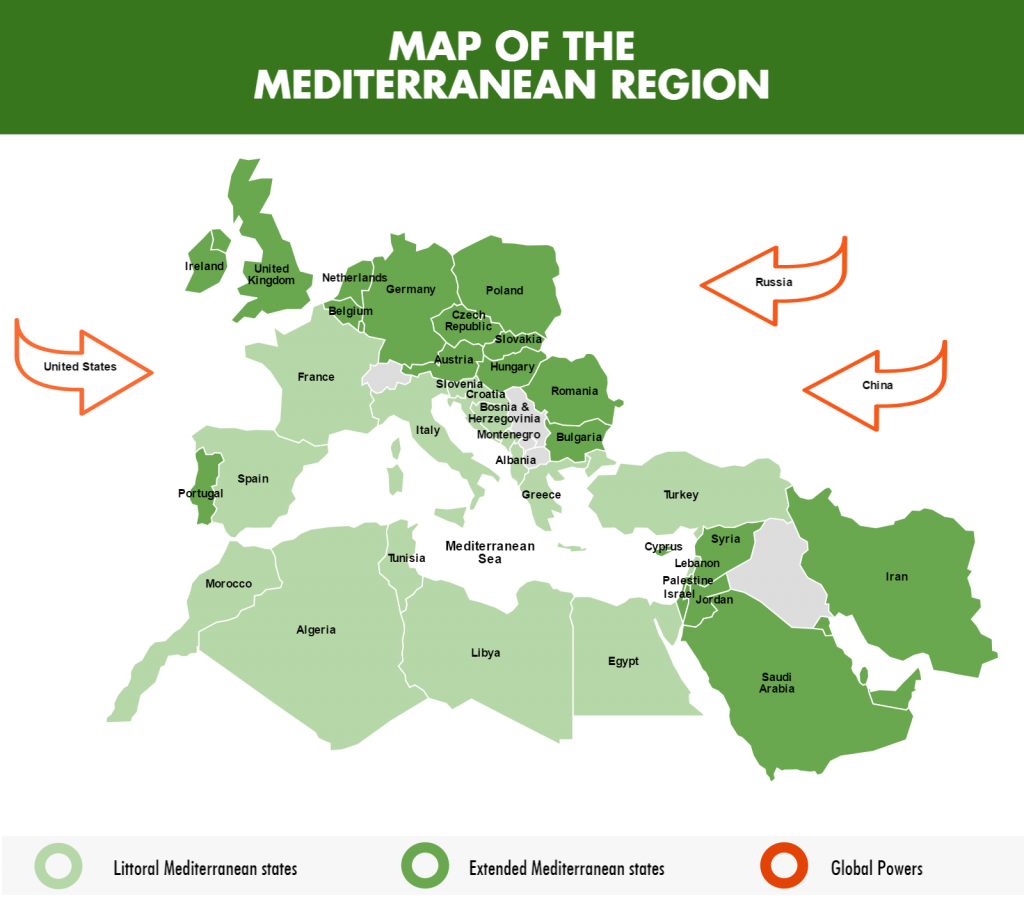

The Mediterranean is at once a coherent and bounded geographic space—a body of water—and it is also a broader and fluid community.3For a treatment of the Mediterranean as a concept, see Michelle Pace, The Politics of Regional Identity: Meddling with the Mediterranean (London and New York: Routledge, 2005). It consists of twenty-two coastal states as defined by the United Nations.4The United Nations lists Albania, Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus/Northern Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Palestinian Territories/Gaza, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey as coastal states. See United Nations Office of Legal Affairs, Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs, “Coastal States of the Mediterranean Sea,”2012, http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/mediterranean_sea.htm. It is sometimes defined as the forty-three Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) countries, including twenty-eight EU members and fifteen littoral states.5The Union for the Mediterranean is an inter-governmental organization created in July 2008 in an effort to strengthen the Barcelona Process, which is the EU’s structure for strengthening relations between the EU and the countries of North Africa and the Mediterranean. Full list at the Union for the Mediterranean website, http://ufmsecretariat.org/ufm-countries/. This study treats the Mediterranean as extending beyond a core set of littoral states, to include an expanded set of neighboring states and global powers with strong interests and influence in the region (e.g., Russia and the United States).

This report outlines the underlying drivers of change that are likely to shape the future and sketches four plausible scenarios for the year 2030. The scenarios are not meant to represent best and worst cases; each scenario incorporates both positive and negative developments in different ways and to different degrees. The final section offers strategic insights into how the transatlantic community and its regional partners might work together to shape the region’s future.

Drivers of change in the Mediterranean

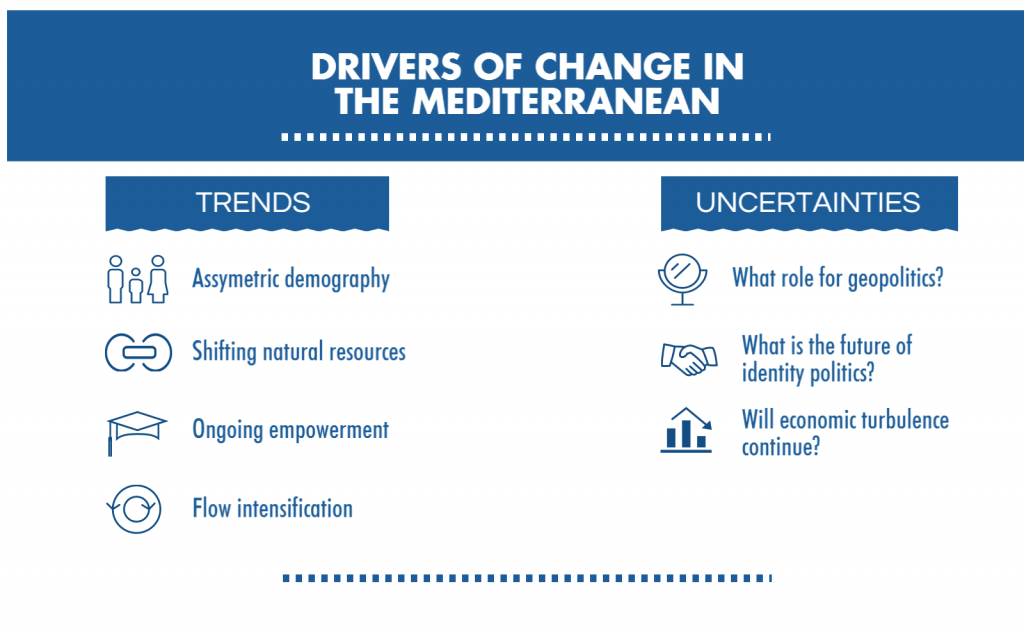

This study identifies core drivers of change that will shape the Mediterranean out to 2030, defined as trends on the one hand and uncertainties on the other. Trends are phenomena where the direction is probable, hence can be forecast with some confidence into the future; uncertainties are phenomena where the direction might be unknown (they can go left or right, up or down) but the impact will be significant regardless of the direction.6This distinction is roughly the same as that presented in Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, 2012, 3. Trends and uncertainties can be good or bad, stabilizing or destabilizing, depending on how they unfold.

Trends

Asymmetric demography

Demographic trends are the most predictable drivers of change, and the Mediterranean of 2030 will reflect population changes on three continents—Africa, Asia, and Europe. These changes follow global patterns. Trend lines everywhere indicate slower population growth, lower fertility, aging societies, and greater longevity.7United Nations, World Population Prospects: Key Findings & Advance Tables, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (New York, NY: 2015), www.esa.un.org. Populations are still growing fast in some parts of the world—including in Africa—but the trend lines suggest that overall population should plateau everywhere and begin to decline by the year 2100.8Daniel Gros and Cinzia Alcidi (Eds), The Global Economy in 2030: Trends and Strategies for Europe Centre for European Policy Studies, November 2013, http://europa.eu/espas/pdf/espas-report-economy.pdf, iii.

Mediterranean societies are moving in all of these directions, but they lie at different points along a continuum. Asymmetric Demography refers to an aging population in Europe, a still-young but now-aging population in the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region, and the world’s fastest growing and very youthful populations south of the African Sahel.

On an elderly-to-youthful continuum, European countries are the oldest on average compared with MENA countries and countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Europe is well past its demographic peak, containing some of the oldest populations on Earth.9Maria Carella and Alain Parant, “Demographic trends and challenges in the Mediterranean,” South East European Journal of Political Science (SEEJPS) II, 3 (2014), 10-21. Fertility rates all across Europe are below replacement (defined as roughly 2.1 children per woman), and while rates could inch upward (from 1.6 now), such increases will not prevent a shrinking population over time.10United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, World Population Prospects: Key Findings & Advance Tables (New York: United Nations, 2015), www.esa.un.org, 4. European economies thus face demographic challenges arising from a high-dependency ratio (the ratio of non-workers to workers).

MENA countries are following the European trend toward aging, but they are not yet nearly as old. Since 1960, the MENA region also has experienced a sharp fall in fertility (from 7.0 children per woman in 1960 to 2.9 in 2009).11United Nations Development Program, World Population Prospects: 2006 Revision, Population Database online, September 2007, www.esa.un.org/unpp/. Despite this steep decline, the region’s population will continue to grow due to fertility rates that are still above replacement. Moreover, the region will remain young to 2030 and beyond. Workers in MENA are globally connected and will be inclined to seek economic opportunity elsewhere in the world if their own economies fail to deliver on employment.12Philippe Fargues, Emerging Demographic Patterns across the Mediterranean and their Implications for Migration through 2030 Migration Policy Center Report, November 2008, 13-14.

Finally, Africa has the world’s fastest growing population, and sub-Saharan Africa has the highest fertility rates on Earth: average rates are expected to fall from about 4.7 children per woman now to 3.1 in 2050, and will reach replacement levels only around 2100.13United Nations, World Population Prospects: Key Findings & Advance Tables, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (New York, NY: 2015), 3, www.esa.un.org. As is true in MENA, sub-Saharan Africa is home to globally connected youth, a great many of whom can be expected to migrate in search of opportunities—assuming their own countries do not deliver on jobs and wages in the years to come.

Asymmetric Demography refers to these stark differences across the basin, between more youthful societies to the basin’s south and east and more aging societies to its north. The expectation is that asymmetry will drive migration, with youthful people from poorer countries seeking employment in older and wealthier ones. Pressure for migration will remain strong even if refugee flows ebb (i.e., if the Syrian conflict is resolved, and refugee flows fall). Countries around the Mediterranean can expect strong migratory flows for the next fifteen years.

Shifting natural resources

The US National Intelligence Council’s (NIC) groundbreaking futures study, Global Trends 2030, estimated that global demand for the core natural resources of food, water, and energy will grow by roughly 35, 40, and 50 percent, respectively, over the coming two decades.14ODNI, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, iv. At the same time, climate change will add to this challenge, squeezing natural resource availability through greater heat and more frequent drought, floods, and other natural disasters.

The Mediterranean is especially vulnerable to resource stresses. As a largely arid or semi-arid region, fresh water scarcity represents the Mediterranean basin’s primary resource vulnerability. Of the littoral states, the most vulnerable are on the Mediterranean’s southern and eastern rim. On the water supply side, the MENA region is the most arid in the world. By 2030, climate change is likely to stress water resources in these countries even further, owing to higher temperatures (which increase evapotranspiration) and reduced precipitation. Unfortunately, constrained and shrinking water supplies will be under increasing pressure from rising water demand, owing to high population and economic growth. Various studies have confirmed that the basin’s southern and eastern littoral countries are facing a difficult water future. A widely cited 2012 study, for example, concluded that water supply in MENA countries would shrink 12 percent by 2050, while demand would increase by 50 percent.15P. Droogers et al., “Water resources trends in Middle East and North Africa toward 2050,” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 16, (2012), 1-14. A recent World Bank study came to the discouraging conclusion that even if MENA countries incentivized water efficiency and invested in water-efficient technologies, in 2050 they still would suffer GDP contraction (more than 6 percent annually) due to a lack of water. “These regions,” the Bank understated, “will need to take more robust measures to address water scarcity.”16World Bank, High and Dry: Climate Change, Water, and the Economy World Bank, 2016, 1-4, 45 (quotation, 45).

In a basin so water stressed, food production becomes critical. MENA states are already vulnerable to food shortages and price shocks arising in other parts of the world, in large part because these states do not produce enough food to support their populations. The onset and timing of the Arab uprisings demonstrate this vulnerability. Food prices were not the main cause of the Arab uprisings in 2011, but high global food prices had put these societies under significant pressure.17Caitlin E. Werrell and Francesco Femia (eds), The Arab Spring and Climate Change: A Climate and Security Correlations Series, Center for American Progress, (February 2013). Assuming MENA states are unable to overcome the food-water constraint and begin producing much larger amounts of food for themselves, they will become more vulnerable to the impacts of bad harvests, price shocks, and steadily rising food demand in other parts of the world.

There are bright spots, however, in the Mediterranean’s natural resource story. Water, ironically, is one of them. Despite aridity, Israel is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost water innovators, whether in water management, water efficiency (as just one example, Israeli scientists invented drip irrigation in the 1960s), or desalination. If Israel’s lessons could be transferred wholesale to the rest of the region (admittedly a difficult proposition), the Mediterranean’s chronic water scarcity might be overcome.18See generally Seth Siegel, Let There Be Water: Israel’s Solution for a Water-Starved World (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015).

Energy, too, is a bright spot: put bluntly, the Mediterranean is awash in energy. Algeria is a major supplier of hydrocarbons to Europe, as was Libya before its civil war. Several states—Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus—are, or could become, energy rich if gas resources in the Eastern Mediterranean can be developed and brought to market. Finally, the potential in renewables is almost without limit, especially on the southern shore of the Mediterranean. Renewable trends in the basin are following those found everywhere in the world—technological change plus scaled production are driving prices downward. Solar potential in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula is among the best in the world; countries in these regions now produce solar electricity at some of the world’s lowest prices.

Although the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have been major drivers of renewables investment in the MENA region, over the last few years several Mediterranean states (especially Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, and Jordan) have been dramatically increasing their solar power investments.19For a quick country overview, see Middle East Solar Industry Association, Middle East Solar Outlook for 2016, 2016, http://www.mesia.com/wp-content/uploads/MESIA-Outlook-2016-web.pdf, 5-8. This development carries great potential for energy independence, economic growth, and jobs creation on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean in particular.

Ongoing empowerment across the Mediterranean will not be uniform . . . and will not result in a unified vision for societal change.

Ongoing empowerment

empowerment” to signify how the power of increased wealth and education, greater life-span, and personalized technologies for billions of people add up to a tectonic shift in world affairs. Global Trends 2030 asserted that individual empowerment would shape the world to 2030, for better and for worse. The NIC maintained that empowerment might lead to positive outcomes (including poverty reduction and the closing of gender gaps), but it also argued that empowerment has a darker side, wherein bad actors (terrorists, criminals, and cyber hackers) would have the means to inflict even greater damage on the world.20See Megatrend 1: Individual empowerment, ODNI, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, 9-15.

The Mediterranean basin is no exception to this empowerment trend. By global standards, residents of southern EU states enjoy high standards of living, with middle class comforts of every kind. European citizenries are highly connected to the outside world, with few constraints on their abilities to find information from around the world and communicate freely with just about anyone in Europe or elsewhere. Europe’s democratic societies long have given European citizens full political rights to participate in governance, including through the vote and on the street.

Many of these same phenomena exist on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean. Speaking generally, MENA states have youthful and dynamic populations that are well connected to the rest of the world. Most people in the region already have access to advanced information and communications technologies (ICT) including smart phones and other mobile devices. MENA observers routinely point to how the region’s youth, armed with these technologies as well as rising economic, social, and political expectations, are unlikely to sit idle for long. Put in other words, the “new demographic” in the MENA region has “less fear of centralized authority and of anyone telling them to ‘wait a generation’ to take on challenges.”21Sherif Kamel and Christopher M. Schroeder, Economic Recovery and Revitalization, Atlantic Council, February 2016, 3.

This hypothesis is not far off the mark. Individuals—not just youths—were at the center of the Arab uprisings; Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor, is commonly understood to have triggered the onset of the Arab Spring with his self-immolation. The resulting protests were focused, at least in part, on attaining basic individual rights.22Toby Dodge, “After the Arab Spring: power shift in the Middle East?” Conclusion: The Middle East after the Arab Spring, in Nicholas Kitchen (ed.), IDEAS reports, SR011. LSE IDEAS, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2012.

In popular imagination, the revolutionaries were middle class, educated youth with Facebook profiles. Social media likely boosted activity where government repression impinged upon civil society.23Taylor Dewey, Juliane Kaden, Miriam Marks, Shun Matsushima, and Beijing Zhu, “The Impact of Social Media on Social Unrest in the Arab Spring” Stanford University, March, 2012, vii. http://stage-ips.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/shared/2012%20Practicum%20Policy%20Brief%20SocialMedia.pdf Social media also increased global attention, facilitated international reporting, and provided a new process for “bottom-up” news stories. (It also provided a useful tool for suppressing protests.)24Dewey, Kaden, Marks, Matsushima, and Zhu, “The Impact of Social Media,” vii. But satellite television and Al Jazeera—also mass phenomena in the region—were important, perhaps even more important, in spreading information about protests across the MENA region.25Dewey, Kaden, Marks, Matsushima, and Zhu, “The Impact of Social Media,” 10 and 16. Although the Arab uprisings have stalled and, in some places, appear to be heading in reverse, the individual empowerment that at least partially drove the uprisings is an ongoing phenomenon.

Ongoing empowerment across the Mediterranean will not be uniform, consequently, it will not result in a unified vision for societal change. This dynamic might help tear societies apart rather than pull them together, hence contributing to fragmentation. And, of course, empowerment will continue to strengthen bad actors, not just good ones. As terrorists routinely demonstrate, equipping bad actors with more tools only makes them more capable of inflicting pain upon others.

Flow intensification

Trans-Mediterranean trade should continue expanding out to 2030. With a growing Mediterranean population of roughly 500 million people, demand for goods and services within the basin is likely to grow significantly. The Mediterranean is a global superhighway, host to high-volume flows of goods, people, and ideas from all over the world. It contains ancient and well-trodden trading networks, and is home to three of the most important choke points in global trade (the Suez Canal, the Bosporus, and the Strait of Gibraltar). Egypt, attempting to take advantage of increasing trade flows, is expanding the Suez Canal to allow for more and faster transit between Asia and Europe. China has been investing heavily in the basin. Chinese companies have been purchasing (or trying to purchase) ports and other infrastructure, for example the Piraeus Port in Greece, as part of a massive investment program designed to ensure China’s access to markets in and beyond the Mediterranean.26Frans-Paul van der Putten, Chinese Investment in the Port of Piraeus, Greece: The Relevance for the EU and the Netherlands Clingendael, February 14, 2014; Sarah Carr, “Dispatch: President Sisi’s Canal Extravaganza,” Foreign Policy, August 7, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/08/07/sisi-dredges-the-depth-egypt-suez-canal-boondoggle/.

However, the Mediterranean’s future also will be shaped by massive illicit flows. Organized criminal networks are reaping benefits from instability and porous borders to expand operations. Small arms, drugs, and people are trafficked through well-established routes from South Asia to the Balkans, and from Latin America or West Africa into Libya and Italy. These syndicates are large, sophisticated, well equipped, and ruthless in their treatment of human beings.27UN Office of Drugs and Crime, 2014 Annual Report, https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2014/World_Drug_Report_2014_web.pdf; Global Initiative Against Transnational and Organized Crime, “Illicit Trafficking from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean”, 2014, http://www.globalinitiative.net/programs/governance/atom-illicit-trafficking-from-the-atlantic-to-the-mediterranean/; European Parliamentary Research Service, “Illicit Small Arms and Light Weapons: International And EU Action”, 2015, http://epthinktank.eu/2015/07/16/illicit-small-arms-and-light-weapons-international-and-eu-action/arms_tab1/; James Politi, “People traffickers seen as ‘tour operators’ in captive market,” Financial Times, April 24, 2015; Louise Shelley, “Human Smuggling and Trafficking Into Europe: A Comparative Perspective,” Migration Policy Institute, 2014, 4. They are joined by jihadist groups in Syria and elsewhere, which use illicit trafficking to earn revenues.28Prem Mahadevan, “Resurgent Radicalism,” in Oliver Thränert and Martin Zapfe, Strategic Trends 2015: Key Developments in Global Affairs (Zurich: Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich, 2015), 57-58. Foreign fighters and terrorists also move around the basin, with close to 20,000 foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria in 2015.29International Center for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence, “Foreign fighter total in Syria/Iraq,” 2015, http://icsr.info/2015/01/foreign-fighter-total-syriairaq-now-exceeds-20000-surpasses-afghanistan-conflict-1980s/.

The illicit movement of humans is the most distressing flow. The plight of refugees from war zones has become the defining feature of Flow Intensification in today’s Mediterranean. The numbers are staggering. In the EU in 2015, more than 1.2 million people applied for asylum, most of whom were from Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan.30Eurostat Press Release, 44/2016, March 4, 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6. The great majority of these (more than one million) undertook a dangerous sea crossing, with at least another 3,770 dying in the attempt.31“Migrant crisis: Migration to Europe explained in seven charts,” BBC News, March 4, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34131911. The EU granted protection to roughly 333,000 asylum seekers in 2015, representing an increase of nearly three-quarters compared with the previous year.32Eurostat Press Release, 75/2016, April 20, 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7233417/3-20042016-AP-EN.pdf/34c4f5af-eb93-4ecd-984c-577a5271c8c5.

But Europe’s crisis is only the smaller part of a much larger refugee problem in the Mediterranean. Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt are host to more than 4.5 million Syrian refugees.33Amnesty International, “Syria’s refugee crisis in numbers,” February 3, 2016, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/02/syrias-refugee-crisis-in-numbers/. These societies are both much closer to the source of the exodus and are not as wealthy as their European counterparts, hence less capable of dealing with the short- and long-term consequences of millions of desperate foreigners in their midst.

Uncertainties

Like trends, uncertainties are drivers of a region’s future. Unlike trends, uncertainties are less likely, as the term implies. It is best to think of uncertainties in terms of core questions about how a region, in this case the Mediterranean, might unfold fifteen years into the future.

What role for geopolitics

Geopolitical contours, and their impact, are a major source of uncertainty for the Mediterranean basin out to 2030. The Mediterranean will be defined by three sets of geopolitical variables, including: the political trajectories of key regional powers such as Turkey, Egypt, and Algeria; relationships in the Eastern Mediterranean between Turkey, Cyprus, Greece, and Israel; and the roles of external state powers such as the United States, China, and Russia.

Turkey, Egypt, and Algeria, three of the most important littoral states, face uncertain political futures. The United States has traditionally invested in Egypt and Turkey as bastions of regional stability. It is treaty-bound to defend Turkey and has put tens of billions of dollars into the Egyptian military. However, Turkey’s President Erdogan has suppressed opposition in the aftermath of the attempted coup of July 2016, pointing to a tenuous state of affairs. More broadly, Turkey’s internal tensions (including the lack of a political settlement with an armed Kurdistan Workers’ Party) plus potential for spillover from the Syrian conflict point to a future characterized more by risk than stability. Egypt, too, remains in a tenuous position, years after the Arab uprising first disrupted the country’s politics. Egypt looks now as it did in 2010, with “struggles between the military and businessmen for economic and political power, human rights abuses, economic woes, and jihadi groups in the Sinai.”34Michelle Dunne and Nik Nevin, “Egypt Now Looks a Lot Like It Did in 2010, Just Before 2011 Unrest,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, 2015, http://carnegieendowment.org/2015/12/16/egypt-now-looks-lot-like-it-did-in-2010-just-before-2011-unrest-pub-62297. Algeria, too, is a fragile state that faces a difficult political environment and an uncertain future.

Geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean region among Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel will play their part in shaping the region.35See for example Jean-Loup Samaan, “East Mediterranean Triangle at a Crossroads,” Letort Paper, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, March 2016. Shifting dynamics have unleashed new patterns of cooperation and competition. Cooperation between Israel, Greece, and Cyprus is on the rise, in part, because of the gas discoveries and interest in getting those resources to market. Cyprus remains divided, but there is a window to make progress on the entrenched conflict, and an opportunity to resolve decades of institutional deadlock between NATO and the European Union. The future of Cyprus and its political relations with Greece and Turkey, and the future relationship between Turkey and Israel are all unknown. The evolution of these relationships, however, and the patterns of competition and cooperation that they generate will be a key feature of the Mediterranean 2030 landscape.

Finally, as the Mediterranean globalizes, the priorities of its biggest institutional actor, the European Union, and the largest extra-regional actors will be critical. The EU will be deeply engaged in the Mediterranean, but the nature of that engagement will be restructured. In 2016, the EU produced a European Global Strategy that provides some direction, but few specific details.36Jan Techau, “The EU’s New Global Strategy: Useful or Pointless?” Carnegie Europe, July 1, 2016, http://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/?fa=63994.

The United States, meanwhile, is likely to remain the most important external actor, even in the wake of the Obama administration’s attempted rebalance toward Asia.37Martin Indyk, “The end of the US-dominated order in the Middle East,” Brookings, March 15, 2016. One result of the rebalancing rhetoric has been the creation of a new political space for other powers, especially Russia, China, and the Gulf states to expand their influence.38Ian Lesser, “The United States and the Future of Mediterranean Security: Reflections from GMF’s Mediterranean Strategy Group,” GMF Policy Brief, April 2015. Each has their own interests in the region and their own reasons to be present, of course, beyond perceived US disengagement.

Conflicts in Syria and Iraq now draw global powers into the Mediterranean.39Petros Vamvakas, “Global Stability and the Geopolitical Vortex of the Eastern Mediterranean,” Mediterranean Quarterly 25, 4, Fall 2014, 124-140. Russia’s intervention in Syria raises questions about its longer-term interests in the region. Its priority is to be seen as a great power in the Middle East, and its 2015 naval exercises with China in the Mediterranean were designed, in part, to show that presence and reach.40Elizabeth Wishnick, “Russia and China Go Sailing: Superpower on Display in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Foreign Affairs, May 26, 2015, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2015-05-26/russia-and-china-go-sailing. Russia’s diplomatic interests also include bolstering the Assad regime, Russia’s long-time ally, and ensuring that Assad remains part of any peace deal. Russia has an interest in continued access to its Mediterranean port at Tartus and in securing economic interests such as its grain exports to Egypt and elsewhere. It also has energy and tourism interests.41Vladimir Bakhtin, “Russia: Returning to a Stable Presence,” in Daniela Huber et al., The Mediterranean Region in a Multipolar World: Evolving Relations with Russia, China, India, and Brazil German Marshall Fund, 2013, 1-10. Russia’s long-term engagement in the region remains uncertain, because there is no Russian strategy for the Mediterranean per se, and there are real doubts as to whether Russia will be able to finance extensive engagement out to 2030.

[P]eople are asking basic questions about who they are and what qualifies them as members of their community.

China’s role in Mediterranean geopolitics is limited, but its presence is growing. China has established ties through infrastructural investment and trade as part of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) vision.42One Belt, One Road is a Chinese government “blueprint” calling for “increased diplomatic coordination, standardized and linked trade facilities, free trade zones and other trade facilitation policies, financial integration promoting the renminbi, and people-to-people cultural education programs throughout nations in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa”. See Jacob Stokes, “China’s Road Rules: Beijing Looks West Toward Eurasian Integration,” Foreign Affairs, April 19, 2015, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/2015-04-19/chinas-road-rules. Its investment in the Greek port of Piraeus is likely to deliver financial returns, improved China-to-Europe maritime trade connections, and greater political leverage. Energy is also a major concern (China’s oil imports grew from $664 million in 1980 to $236 billion thirty years later).43Ted C. Liu, “China’s Economic engagement in the Middle East and North Africa,” Fride Policy Brief No 173, January 2014. China now imports more oil from Arabian Gulf countries than from any other source.44Kerry Brown, “China: the limits of neutrality,” in Kristina Kausch (Ed.), Geopolitics and Democracy in the Middle East (Madrid: FRIDE, 2015), Figure 1, 105. China and Egypt, meanwhile, upgraded their relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” as China works to strengthen the Egyptian economy and improve links across Egypt’s north, which gives the OBOR network an opening into Africa.45Alexander Neill, “Xi Makes Economic Inroads in Middle East,” IISS Voices, January 22, 2016, http://www.iiss.org/en/iiss%20voices/blogsections/iiss-voices-2016-9143/january-671d/xi-visit-to-middle-east-0a48. China has successfully evacuated workers from Libya, contributed to counter-piracy operations, and is opening a naval logistics base in Djibouti. Its activities lay the foundation for more engagement but risk drawing China into geopolitical conflict, undermining its commitment to neutrality abroad.

What is the future of identity politics?

Societies around the Mediterranean are grappling with the politics of identity. Driven in part by a perceived loss of control over their destinies, people are asking basic questions about who they are and what qualifies them as members of their community. The Mediterranean map of state borders now seems old-fashioned in light of rapidly shifting identities. The resolution of these questions will shape the region out to 2030.

Identity politics have been front and center in the headlines since the onset of the Arab uprisings in 2011. During a long period of consolidation after the 1960s, resource-rich states in the Arab world relied on service provision to establish their legitimacy and employed traditional means of authoritarian control.46Michael C. Hudson (ed.), The Crisis of the Arab State, A Study Group Report, Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, August 2015, 2; Lisa Wedeen “Abandoning Legitimacy: Reflections on Syria and Yemen,” in Michael C. Hudson (ed.), The Crisis of the Arab State, A Study Group Report, Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, August 2015, 27. Since the onset of the Arab uprisings, this pattern of state consolidation has broken down completely. Four states in the Middle East are now destroyed or engaged in civil wars—Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Libya. Others have since witnessed mass protests and are still in early stages of a very long process of transition.47Andrew Engel, Libya as a Failed State, Causes, Consequences, Options, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Research Note 24, November 2014, 1.

The political vacuums that have emerged since the uprisings have enabled this fluidity in identity politics. ISIS has stepped into vacuums in Syria, Iraq, and Libya to impose its own variant of identity upon populations already questioning it. ISIS thrives on sectarian grievances and an anti-modern narrative, amplified by social media. Inspired by a radical form of identity politics, new recruits sign up in search of purpose and belonging.48Richard Barrett, The Islamic State The Soufan Group, October 28, 2014, 4-6.

The European Union and its member states are subject to their own identity challenges. For years, the EU has faced fundamental, even existential, questions arising from the Eurozone crisis, anemic economic growth, and an erosion of trust in institutions. Recently, and perhaps most worrisome, has been a rebirth of xenophobia-fueled nationalism. Europeans are asking their own questions about European and national identities. The United Kingdom has voted to quit the European Union, while populist sentiment and fringe, anti-establishment parties are common across the continent. The Brexit vote highlighted this identity challenge within Europe.

Will economic turbulence continue?

Mediterranean economies have suffered through a long period of economic turbulence. Fiscal and monetary crises, dramatic swings in the global commodity cycle (food and oil prices), political upheaval, and violent conflict all have scarred basin economies. The question going forward is how severe that turbulence will be, and whether turbulence will continue to drive Mediterranean economies downward.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, Europe has faced exceedingly difficult economic headwinds. Debt crises have afflicted Eurozone economies, with Greece’s struggles the most visible example. But Europe faces other significant challenges. Unless solved through immigration, Europe’s chronic aging will be a major structural obstacle to high growth (see Asymmetric Demography). Aging intersects with Europe’s difficult competitive position in the global economy, wherein Europeans’ high wages and benefits (e.g., strong pensions) conflict with a high dependency ratio (number of non-workers to workers) and low labor productivity growth.49International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: Uneven Growth, Short- and Long-Term Factors, April 2015; Gros and Alcidi, The Global Economy in 2030; European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (ESPAS), Global Trends to 2030: Can the EU meet the challenges ahead? (Brussels: ESPAS, 2015), http://espas.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-can-eu-meet-challenges-ahead. Europe, however, also possesses strengths, including well-educated, well-connected workforces; a huge consumer economy; and highly functional governance.

The MENA countries also face an uncertain economic future. MENA economies have been hampered by relatively low levels of formal sector employment, low levels of entrepreneurship and access to private sector finance, and the spillover consequences of the region’s many conflicts (the Syrian conflict alone has had negative economic impacts on all its neighbors).50International Monetary Fund, Regional Economic Outlook Update: Middle East & Central Asia, May 2014. To date, MENA’s youth bulge has not translated into high formal-sector employment, especially for youth and women. And educational systems in the region tend to be stratified by background more than in other world regions, leaving a great many people behind. Moreover, secondary and tertiary educational systems in the region have struggled to employ their graduates.51On innovation, see Christopher M. Schroeder, Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). On the consumer market, see Vijay Mahajan with Dan Zehr, The Arab World Unbound: Tapping into the Power of 350 Million Consumers (New York: Jossey-Bass, 2012). On labor and education, see Mathew J. Burrows, Middle East 2020: Shaped by or Shaper of Global Trends? Atlantic Council, 2014.

Commodities complicate the Mediterranean’s economic forecast. Commodity price swings, including global food prices, are particularly important given high food import dependency in many MENA economies. Global energy patterns are equally important.52Information in this paragraph from Silvia Colombo and Nicolò Sartori, Rethinking EU Energy Policies Towards the Southern Mediterranean Region IAI Working Papers 14, Istituto Affari Internazionali, November 2014. On the supply side, North African producers (Algeria and Libya, primarily) have been major exporters of oil and gas to consumers around the basin for decades. Egypt, too, is a major producer of hydrocarbons, but historically much of that production has been to meet domestic demand. And some basin countries are busy expanding their renewables portfolios, as discussed above (e.g., Morocco and Egypt). The significant undersea gas fields that have been discovered recently in the Eastern Mediterranean could reshape the basin’s energy economy, but the repercussions of this discovery are unknown. The 2015 discovery of the “supergiant” Zohr field in Egyptian waters could be one of the world’s largest. If brought online, its estimated 30 trillion cubic feet of natural gas has the potential to meet Egypt’s domestic demand into the 2020s.53Christopher Adams, Heba Saleh, and John Reed, “Gas find promises sea change in the Med,” Financial Times, September 6, 2015. On Eastern Mediterranean gas discoveries and their implications in general, see Sarah Vogler and Eric V. Thompson, Gas Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Implications for Regional Maritime Security, German Marshall Fund of the United States, March 2015.

On the demand side, both southern European and North African consumers (especially in Tunisia and Morocco) long have relied on Algerian and Libyan oil and gas exports. For the region’s major oil exporters, a key challenge will be to diversify their economies, especially in the face of low oil prices.54IMF, Regional Economic Outlook Update: Middle East & Central Asia, 3-6.

Nearly all prescriptions for Mediterranean economies advise shifting to knowledge economy platforms. Innovation has become a panacea for righting economic problems around the world, but creating innovative economies is much easier said than done, particularly in societies that are risk-averse—which tends to be the case in states around the Mediterranean. With some notable exceptions, e.g., Israel, in general, Mediterranean countries have struggled to create innovative economies.55On this issue, see Peter Engelke, Brainstorming the Gulf: Innovation and the Knowledge Economy in the GCC, Atlantic Council, 2015, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/brainstorming-the-gulf-innovation-innovation-and-the-knowledge-economy-in-the-gcc, and Peter Engelke and Robert A. Manning, Labor, Technology, and Innovation in Europe: Facing Global Risk through Increased Resiliency, Atlantic Council, 2013.

Yet, there are many who remain buoyant about the prospects of Mediterranean economies with respect to the knowledge economy. Take the MENA states, which are usually considered among the least innovative in the world—a view that is only partially justified. There is a burgeoning entrepreneurialism in many parts of the region, plus a large and growing consumer market. MENA states’ youthfulness could be an enormous asset if it can be made productive (from 2005 to 2030, the MENA region’s working age population is expected to increase by 156 million, while that of EU member states is expected to decrease by 24 million).56Fargues, Emerging Demographic Patterns across the Mediterranean, 9. MENA citizens are well connected to the rest of the world and are better educated than in the past, at least in terms of number of years of education.57World Bank, “Education in the Middle East and North Africa,” 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena/brief/education-in-mena; World Bank, “Infrastructure Deployment and Developing Competition: Broadband Networks in the Middle East and North Africa,” 2012, 59, http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/MNA/Broadband_report/Broadband_MENA_Chapter3.pdf; Deloitte and GSM Association, “Arab States Mobile Observatory,” 2013, 10, http://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/GSMA_MobileObservatory_ArabStates2013.pdf.

There is thus a strong case that MENA societies are ripe for economic revolution, possessing the youth, vitality, and drive required to transform themselves into dynamic innovation economies. But these conditions will not result in innovative economies by themselves; smart policies, ranging from education and skills training to intellectual property protection to the right investments, will be required.

Scenarios for the Mediterranean in 2030

Based on the analysis in the first part of this report, this section presents four plausible scenarios (based on the drivers and uncertainties discussed) for the Mediterranean basin to the year 2030. These scenarios are written in the past tense, as if a narrator is reflecting on what has transpired in the Mediterranean basin between the years 2016 and 2030. These scenarios are titled Erosion, Drawbridges, Power Play, and Club Med.

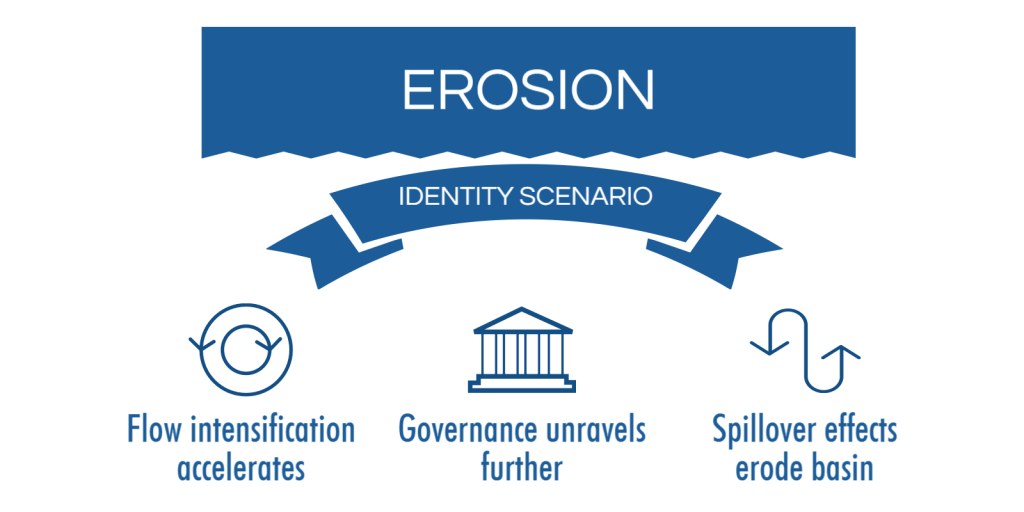

Erosion

Erosion is the closest to a “default” scenario out to 2030—wherein events unfold along their most likely trajectories.

In the Erosion scenario, identity politics will force wrenching debates about citizenship and call into question governmental legitimacy. With heterogeneous, rapidly shifting, and often incompatible forms of identity existing side by side in many countries, governments will be forced to manage centrifugal politics that often threaten to spin out of control:

Looking back from 2030, over the past decade-and-a-half, stability in the region’s hot spots—Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen—proved impossible to sustain. Although there were attempts to broker settlements, solutions tended to be short-lived, fragile, or both. The region’s national boundaries were not redrawn to reflect shifting realities on the ground; Syria and Libya remained sovereign states, but their sovereignty was more in name than reality as separatist groups, including ISIS-like quasi-states, claimed territorial control.

As a result, spillover effects continued to spin outward, generating even greater foreign policy headaches for regional and global powers. Radical terror groups proliferated. Although these groups remained fragmented, they spread across the region, including to some GCC states. States that neighbored the core conflict zones, such as Turkey, Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, bore the brunt of this burden. Splintering loyalties and growing radicalism characterized their politics. Turkey, for example, found no lasting solution to its Kurdish dispute, in part because the ongoing conflict in Syria and Iraq permanently transformed the Kurdish question into a transnational one.

Flow Intensification accelerated, especially the illicit trafficking of humans, drugs, weapons, and counterfeit goods as weak states around the region became sources of contraband and transit zones for criminal enterprises. Although refugees continued to flee conflict zones, these flows spiked and fell dramatically as events on the ground ebbed and flowed. More consequential, in terms of sheer numbers, were the many economic migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia who, driven by the logic of Asymmetric Demography, continued to find their way through the Mediterranean’s weak and fragile states and into Europe. Although there were exceptions, the large migrant and refugee communities in countries around the basin were marginalized. Their large numbers, their grievances and frustrations, and the resentments of local people in the receiving countries—many of whom threw up legal, social, and economic barriers to the newcomers—all worsened identity politics.

Mediocre economic performance continued around the basin through the 2010s and 2020s. Although natural gas exports from the Eastern Mediterranean provided a fillip, gas proved to be neither an economic nor geopolitical game-changer (the gas fields and economic windfall were not as large as forecasted). Global energy trends did not help, as oil and gas markets never emerged from burgeoning global supply coupled with flat global demand. Energy exports continued to offer prosperity to some Mediterranean economies, but hydrocarbons no longer proved as great a source of wealth as in the past. Those states that made strategic investments in renewable energy, like Spain and Morocco, saw those investments pay off. While renewables did not replace hydrocarbons for electricity production, their pricing became competitive with fossil fuels by the 2020s.

While the European Union continued to exist as a coherent supranational body, the EU struggled with increasing disunity on almost all fronts58.The authors thank Fran Burwell for her thoughtful insights about European futures. Europe’s challenges were both economic and political. Economic turbulence buffeted the continent, with growth rates over the 2015-2030 period while neither strong and sustained, nor evenly distributed. The north-south economic divide remained, with southern European states remaining weak relative to their northern peers. Although the EU muddled through, managing to stay intact and keep Greece in the Union, the UK spun out with a hard Brexit, harming both the British and European economies.

Meanwhile, the identity driver reworked European politics. Sustained, large-scale migration continued to erode European trust in institutions, spurring nationalism, xenophobia, and antiestablishment sentiment across the continent. EU member states continued to throw up obstacles to immigration. The EU, facing an existential threat, managed over time to articulate coherent immigration policies by strengthening the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), bolstering its maritime operations, crafting a migrant distribution system, and preserving the Schengen system.

Yet, these policies addressed symptoms rather than causes. Neither the EU nor individual European states found the political will to tackle the Mediterranean’s core problems. Internal divisions, political disagreement, scarce resources, and the seeming intractability of the basin’s problems all prevented the EU from formulating a feasible grand strategy toward the region.

Other powers in the Mediterranean also struggled, and geopolitical competition intensified among them. The key powers entered into ad hoc and fragile coalitions to deal with symptoms when their interests overlapped. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Israel, and other regional powers all struggled to contain the fires that threatened their neighborhoods, but none found a coherent path forward.

Russia retained its newfound activism in the Mediterranean, but had neither the resources nor the influence to do much beyond shoring up its support for Syria’s Assad regime, which had managed to retain its foothold on power (Bashar al-Assad is only in his mid-sixties in 2030). Russia focused on a narrow agenda, including maintaining access to a Mediterranean base, and occasionally finding common ground with Iran and its non-state allies.

Although China had significant economic investments in countries around the Mediterranean in 2030, it continued its strategy of political disengagement. Wary of entangling itself in conflicts, China acted only to ensure ongoing access to its supply chain and export markets (through anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and elsewhere). China, while worried by the spread of radicalism toward Europe and Asia, with an eye on its own western provinces, nonetheless was insufficiently induced to become a major regional player.

Finally, the United States remained engaged, but limited in both aspiration and means. Much like the Vietnam War, the Iraq War left a decades-long shadow over the US body politic and its foreign and security policy communities. Over the entire period to 2030, the United States remained disinclined to commit massive resources to the region, especially human resources. America’s dwindling reliance on Middle East oil only contributed to this predisposition.

At the same time, the United States refused to disengage entirely. Economic interests, including energy interests, remained, but geopolitical competition and the ongoing fear of terrorism provided greater motivation. The activism of other powers (e.g., Russia and Iran) induced American policy makers to engage when and where they felt necessary. Ongoing crises around the Mediterranean forced Washington into a never-ending quest for stability, which proved elusive.

Drawbridges

Drawbridges represents the populist scenario, wherein countries will seek to reduce their exposure to risks in and around the basin and elsewhere. Europe is at the center of this scenario:

Over the 2015 to 2030 period, European countries never recovered fully from the Economic Turbulence that started with the 2008 financial crisis. While there were some bright spots, in general European economies suffered from consistently low growth. Despite the best of efforts, in the late 2010s Greece wound up leaving the Eurozone, leading to other southern European withdrawals and paring the zone down to a handful of core countries led by Germany. Greece’s exit followed that of Great Britain, which left the EU, in part, because its electorate began to associate membership in the EU as an economic drain rather than an asset. By the late 2010s, the EU was facing a deep legitimacy crisis.

European countries’ poor economic performance resulted from chronic aging, per Asymmetric Demography, and from global challenges. Like the US middle class, the European middle class continued to be squeezed by relentless pressure on wages, due, in part, to intense competition from well-skilled workers abroad. But the bigger challenge, felt everywhere, was from labor-replacing technologies. During the 2020s, artificial intelligence began to expand its grip on labor markets, eliminating or dramatically reducing employment in scores of labor categories, including professions such as accounting and law.

The economic anxieties that began after 2008 in Europe therefore intensified through the period, in some places dramatically. This situation worsened as Europeans began to associate poor economic performance with Flow Intensification from Europe’s south, especially flows of people—economic migrants, political refugees, and in some cases foreign fighters and terrorists. Although economists and some politicians argued that Europe would benefit from an influx of youthful workers, fear increasingly dominated European politics. Migrants and refugees become scapegoats for Europe’s economic problems, illicit drug and weapons trafficking, terrorism, and violent crime.

For these reasons, migrants and refugees, in 2030, are flashpoints for a broad Hearts and Minds debate in Europe. Nationalist, anti-immigrant, and Eurosceptic parties have become more common and powerful as citizenries, concerned about both their economic fortunes and their cultural identity, defined themselves in opposition to the outsiders who are in their midst.

Surging populism resulted in clashes within the EU. Member states, unilaterally at first, crafted strong policies against the Mediterranean’s illicit migrant flows. Some European states, particularly in eastern and central Europe, simply refused entry to refugees and migrants. Populations in nearly all member states, including those in northern and western Europe, struggled to accept an EU-wide arrangement to share the responsibility of accommodating refugees. As a result, borders began to be closed and Schengen broke down. The EU, facing an internal revolt, assembled an aggressive interdiction policy including forced repatriation, leading to even larger humanitarian challenges around the Mediterranean region. Those migrants that remained in Europe, including some second- and third-generation migrants, continued to live marginalized existences.

Europe’s core interest became the protection of Europe, and the continent turned its back on the hardest questions. Individual member states remained active in parts of the basin (for instance, France in North Africa and the Sahel), but policy and action were narrowly focused, driven overwhelmingly by hard security considerations. Trade in legitimate goods continued around the Mediterranean, but the inward turn of so many states negatively affected these flows. Europe’s increasing transition to renewable energy sources decreased fossil fuel imports from MENA states.

Other states around the Mediterranean reached similar conclusions. Many were caught in a real bind, housing refugees from nearby crises and economic migrants from distant regions (South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa especially). Europe’s actions worsened this situation, with migrants having fewer pathways into Europe. So, the states that had the capacity to act, including Turkey, Israel, Egypt, and the GCC states, also began to seal themselves off from these flows.

While developments according to the Drawbridges scenario soothed a few headaches (it reduced illicit flows), it made others much worse. The Mediterranean’s southern and eastern states suffered from even poorer economic performance, and their governments resented Europe’s turn away from them. A lack of resolution to regional conflicts as well as the presence of millions of displaced persons, most of whom struggled to integrate themselves into their host societies, reduced stability while increasing radicalism. Jordan and Lebanon in particular faced exceptionally difficult conditions, with millions of permanent refugees both unwelcome and yet unable to return home.

Effective Mediterranean governance became an impossible task. Europe continued to advance a pro-Mediterranean diplomatic agenda, but it existed far more in name than in deed. Europe’s relations with other countries in the Mediterranean became more difficult in general, as many perceived Europe as indifferent to their plight or even hostile to their interests. Turkey’s relationship with Europe turned even colder than it had been in 2016, with European Union entry definitively off the table and cooperation within NATO almost non-existent. The absence of a strong European presence in the region worsened the US position, and on many difficult fronts, the United States found that it had few willing partners. The United States occasionally brought European states such as France into military coalitions, but these were short-lived and geographically constrained. As in the Erosion scenario, Russia retained a presence in the Mediterranean, but also focused on a narrow agenda. China did not engage politically or militarily and curtailed its investment as the region’s economic promise faded.

Power play

Power Play is the geopolitical scenario, wherein ongoing conflict and political disintegration of the Mediterranean region will escalate the engagement of key global and regional powers:

During the late 2010s, regional and global powers began to reassess how the region’s conflicts threatened their own stability and security. Flow Intensification was the key conduit: Russia, China, Europe, the United States, and regional powers all feared that radicalism would be exported through and beyond the Mediterranean. Rather than withdrawing (which most powers concluded was impossible), all increased their engagement.

The basin became part of a larger geopolitical reordering. Global power politics factored in, with China and Russia increasingly willing to challenge the global status quo as managed by the United States. Mediterranean geopolitics thus began to resemble global geopolitics. Nonetheless, a return to a rigid system of antagonists—as in the Cold War—did not occur, for powers also found opportunities to work together when it served common interests.

The United States remained active in the broader Mediterranean region, yet was unable to fully focus due to strong demand for attention elsewhere in the world. The United States retained an ability to muster action in the basin, but it could not act as hegemon. Its European friends and allies, meanwhile, retained a strong interest in Mediterranean security and stability and the will to cooperate militarily with the United States on occasion. But they, too, lacked the resources, capabilities, and political unity to mount a full-throated and long-term response to the basin’s many challenges.

Russia continued to build on the foothold it had established in Syria through its intervention in late 2015 and was able to expand its military presence, thus adding the Mediterranean to the “zones of friction” between Russia and the transatlantic community. Russia also sought to find allies in a region it saw as undone by the West’s own mishandling in the early 2000s. Some states in the region welcomed Russia’s presence, as it came with the promise of action on pressing issues and with fewer strings attached.

China decided to deepen its presence, transforming itself from an economic player into a diplomatic and military one. Unwilling to risk their significant investments, the Chinese leadership found that it needed to have a more pronounced military presence. Most worrisome to Beijing was how the Mediterranean’s conflicts began to export dangerous ideas and people, which drove China to abandon its passive diplomatic footing. China began a search to establish naval access in and around the Mediterranean. Although these actions were undertaken to safeguard investments and the safety of Chinese citizens working in the region, they had the real effect of showing that the Mediterranean was a region where China could display its power.

The Power Play scenario did not result in either uniform conflict or cooperation. While there were alliances and rivalries, the period resembled more the late nineteenth century than the Cold War. The United States and its partners often found themselves jockeying for position against a more confident Russia and China. But the situation was multipolar rather than bipolar—China and Russia did not present a durable and persistent axis. Hence, there was considerable space for the major powers to slide along a conflict/cooperation scale as events on the ground dictated. Overlapping interests gave rise to shifting coalitions to address state fragility, radicalism, and terrorism.

Despite the possibility that global and regional powers might be able to enforce some stability, the other drivers remained at work. Power Play did not address the diverse challenges and opportunities arising from Asymmetric Demography, Ongoing Empowerment, economic turbulence, and shifting identity.

Most significantly, the identity challenge could not be settled through political solutions imposed from above. As outside powers placed greatest priority on the region’s security, they followed a well-established path to choose short-term stability over long-term political, social, and economic development.

This choice proved to be a dead end, for it cemented long-standing local resentments against outside powers, which were perceived as forcing solutions onto unwilling publics. The long history of global power intervention might have generated stability in MENA for some periods, but it had failed to create legitimacy for the local states and regimes that emerged from that intervention. The application of external military power has not proven effective in state- and nation-building.59Arguments from Shibley Telhami, The World Through Arab Eyes: Arab Public Opinion and the Reshaping of the Middle East (New York: Basic Books, 2013), chapter 1, and Stephen Walt, in Michael C. Hudson (Ed.), The Crisis of the Arab State: Study Group Report, Harvard Kennedy School, August 2015, 30.

Club Med

Club Med is the best plausible scenario for the basin. Fearing the consequences of a Mediterranean that might spin out of control with worldwide ripple effects, global and regional powers will begin to realize that their interests overlapped more than they clashed: