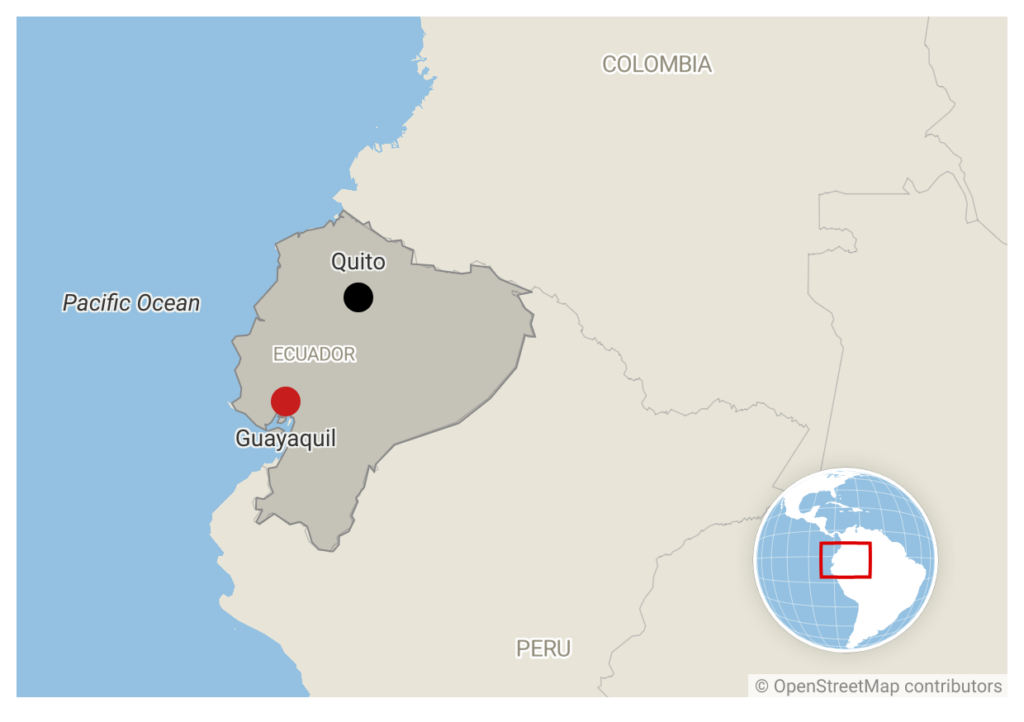

Latin America’s democratic institutions face an existential threat as organized criminal groups evolve from mere trafficking operations into sophisticated providers of parallel governance. In a region long characterized by the world’s highest levels of inequality and violence, nowhere is this transformation more striking than in Guayaquil, Ecuador, where criminal networks have engineered one of the fastest security collapses in recent Latin American history. The city’s swift descent from relative stability in 2021 to the eighth most violent city globally by the end of 2024 reveals how quickly organized crime can exploit institutional weaknesses to establish alternative power structures—a pattern with profound implications for democratic governance across the region.

The first round of Ecuador’s presidential election in February revealed two competing visions for managing this unprecedented crisis. The second round on April 13 promises to crystallize these approaches.

Incumbent President Daniel Noboa champions a technocratic approach pairing economic liberalization with tough security policies—a vision that resonates with urban middle-class voters, who see his business acumen as crucial for modernizing the state’s response to organized crime. His challenger, former Assemblywoman Luisa González, advocates for a return to state-led development, combining expanded social programs with institutional reform over militarization. Her platform has found particular traction among rural and lower-income Ecuadorians, who fondly recall the era of former President Rafael Correa, who advocated for social spending and poverty-reduction initiatives. Yet beneath the electoral rhetoric, a more fundamental question looms: Can either candidate’s vision effectively counter the growing control of criminal networks over Ecuador’s youth?

A laboratory for criminal innovation

Situated between Colombia and Peru—the world’s largest cocaine producers—Ecuador has become a battleground where foreign mafias collaborate with local gangs to control strategic trafficking routes. The interplay of porous borders, entrenched corruption, economic fragility tied to converting its currency to the US dollar, and ineffective security policies has created fertile ground for these transnational criminal enterprises to expand their influence. Yet, Guayaquil’s crisis transcends its role as a trafficking hub. The city has become a laboratory for criminal innovation where organized crime groups have transformed from simple drug trafficking operations into sophisticated political actors. They provide security, economic opportunity, and social belonging to marginalized communities—services the state has failed to deliver.

The mechanisms of this transformation merit close attention from policymakers across the Americas. Criminal organizations in Guayaquil have mastered a strategy increasingly visible throughout Latin America: exploiting the corrosive combination of weak rule of law, endemic corruption, and profound socioeconomic inequality to establish parallel governance structures and weave themselves into the social fabric of everyday life. Through Guayaquil’s port infrastructure, these groups now control an estimated 80 percent of Ecuador’s illegal drug exports, concealing cocaine in expedited shipments of perishable goods such as tea and bananas.

More significantly, they have developed sophisticated recruitment networks that target children as young as eight years old. Durán, just across the river from Guayaquil, is known grimly as the “school of assassins,” where children are groomed through a ruthless drug dealer-to-assassin pipeline. The human cost of this transformation is visible in daily life. The country’s energy crisis has plunged already precarious neighborhoods into prolonged darkness over the course of the past year, with rolling blackouts stretching up to fourteen hours per day. For residents of these fragile communities, the outages have rendered their daily lives into a de facto siege, trapping them indoors as fears of assault, kidnapping, extortion, or falling victim to stray bullets loom large.

Guayaquil’s experience offers crucial lessons about the speed with which criminal organizations can fill governance vacuums. The city’s crisis also exemplifies a broader regional challenge: How can Latin American democracies rebuild state legitimacy while confronting immediate security threats? The answer may determine not just Ecuador’s future but also the trajectory of democratic governance across the region.

A generation under siege

The systematic recruitment of youth into organized crime in Ecuador is part of a disturbing trend across Latin America. Between 2019 and 2023, killings of children and adolescents in Ecuador rose by 640 percent, culminating in at least 770 deaths of minors in 2023. This trajectory mirrors broader patterns in the region, where homicide is the leading cause of death for youth aged ten to nineteen. In Rio de Janeiro, the number of children aged ten to twelve who entered drug trafficking doubled between 2006 and 2017, and an estimated six out of ten members of criminal groups in Ecuador are under the age of nineteen, highlighting an accelerating shift toward younger recruitment across criminal organizations.

The weaponization of educational spaces, a strategy perfected by criminal groups from Medellín to Ciudad Juárez, has found fertile ground in Guayaquil’s most insecure neighborhoods. Students find themselves at the epicenter of this violence, coerced into participation under threat of harm to themselves or their families—sometimes by classmates already ensnared in criminal enterprises. Teachers face constant intimidation and, in extreme cases, have been killed for challenging these incursions—a pattern documented across Latin America’s urban peripheries. In one northern community of Guayaquil, law enforcement estimates that as many as 16 percent of students are linked to gangs.

Criminal organizations across the region have refined their recruitment strategies to exploit socioeconomic vulnerabilities. In Guayaquil, as in Colombia’s Comuna 13 and Mexico’s working-class barrios, criminal groups entice youth from financially unstable families through promises of income, protection, and social status—an understandably appealing alternative to fear, isolation, and economic despair. The tactics are remarkably consistent: houses acquired through forcible eviction are handed over to adolescent members as rewards, peer networks and family members already engaged in criminal activities normalize gang affiliation, and younger children are lured with material incentives such as video games and toys. Girls face particular risks, including sexual exploitation and forced relationships with gang leaders—a gendered dimension of recruitment widely documented in Latin American countries.

Ecuador’s prison crisis—marked by persistent overcrowding and eruptions of violence—further exemplifies a broader regional pattern, in which overcrowded penitentiaries serve as command centers for criminal enterprises. Young offenders enter a prison ecosystem where gang affiliation becomes a matter of survival rather than choice and then return to their communities with strengthened criminal networks.

The crisis in education infrastructure compounds these challenges. Public schools face chronic challenges, from crumbling infrastructure to pervasive sexual violence, further eroding their role as ostensible safe spaces and sanctuaries of learning. When Noboa declared an “internal armed conflict” in early 2024 and the Ministry of Education suspended in-person attendance for Ecuador’s 4.3 million students, the country joined its regional neighbors in seeing education systems buckle under security pressures. The statistics are stark across Latin America: in Honduras, 90 percent of teachers report gang targeting of their schools; in Guatemala, 60 percent of students report fearing school attendance; and criminal groups treated the COVID-19 pandemic as a recruitment windfall, directly targeting students who were forced out of the classroom.

Breaking this cycle requires solutions that address both immediate security needs and underlying structural inequities—including strengthening school infrastructure, implementing socio-emotional learning programs, and supporting youth looking for a way out of gang membership by providing viable pathways to resilience and opportunity—a challenge that has largely eluded policymakers across the region.

A crisis of trust and legitimacy

In Ecuador and many other Latin American countries, the military and police forces play an important role in taking on criminal gangs. At the same time, an overreliance on force can cause its own problems.

For example, the December 2024 murder of four Afro-Ecuadorian boys by military forces in Guayaquil crystallized for many in Ecuador how state violence and impunity can shatter community trust. When the children—aged eleven to fifteen—disappeared, authorities initially blamed gang violence. But CCTV footage later revealed military personnel forcing the boys into a patrol vehicle. One managed to call his father and reported that they had been beaten and their clothes removed; the father appealed to the police to no avail. Seventeen days later, the children’s charred remains were found in a rural swamp. Amid the outrage and grief of the citizen response, the government arrested sixteen soldiers for the forced disappearance of the boys and promised a complete and transparent investigation.

Like similar cases in Latin America, this event highlights how militarized responses to instability can exacerbate the very governance problems they aim to address. Human Rights Watch and Ecuador’s Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights describe the murders as part of “systematic disappearances” that have escalated since security forces were deployed to combat gang violence. In Guayaquil’s periphery, residents report police planting drugs on youth to meet arrest quotas, while documented cases show officers passing informants’ identities to criminal groups—leading to deadly reprisals.

In a cruel paradox, the snake begins to eat its tail: the breakdown in trust erects barriers to—and compromises the effectiveness of—the very institutions and programs attempting to rebuild public confidence, further entrenching community isolation. Residents retreat from public spaces and curtail social activities, fearing surveillance by both criminal groups and corrupt security forces. Community gatherings evaporate, parents keep children indoors, and local markets empty—accelerating the breakdown of social cohesion that once helped neighborhoods resist criminal influence.

The withdrawal of adults from community spaces then results in a mentorship vacuum. Even successful intervention programs struggle to overcome this trust deficit. International nongovernmental organizations, development agencies, and civil society organizations find their work complicated by community suspicions, while those who manage to navigate gang checkpoints often see their efforts disrupted by violence or lack of institutional support. In an environment where state institutions have lost their moral authority, it is unsurprising that many of the young people weighing their options come to view gang membership as rational self-preservation.

Yet, amid this deterioration, community-based initiatives anchored by respected local leaders have demonstrated the power of persistent engagement in leading social repair. The Guayas Community Network of Defenders, comprising eighty trained community leaders, has developed successful initiatives ranging from food-security management to human-rights education. In Guayaquil’s most vulnerable sectors, the Social Youth Movement—a coalition of more than three hundred young people from marginalized communities—has mobilized through “artivism” and political advocacy to combat structural violence while creating leadership opportunities for youth typically targeted by gangs. Their success in areas such as comprehensive sexual education reform demonstrates how organized youth movements can channel their energy toward constructive social change. Meanwhile, community groups such as the Socio Vivienda collective have successfully organized to defend housing rights and resist displacement, even in neighborhoods heavily affected by criminal violence.

While these grassroots movements remain modest in scale, their successes contrast with the ineffectiveness of short-term interventions. The main challenge is expanding these local initiatives while operating in an environment where fear and mistrust run deep. As long as Guayaquil’s authorities fail to hold themselves accountable for institutional abuses, each betrayal of public trust hands another victory to criminal groups seeking to capture youth loyalty.

A generation in the balance

The battle for Ecuador’s democratic future will ultimately be won or lost in marginalized communities where criminal networks have become de facto providers of what the state has failed to deliver—however perverse their methods. Ecuador’s precipitous descent from being hailed as an “earthly paradise” to earning the nickname “Guaya Kill”—a grim rebranding of its once-thriving port city—offers sobering lessons about the fragility of democratic institutions in an era of sophisticated transnational crime. The transformation of Guayaquil’s youth recruitment crisis—from a peripheral security concern to an existential threat to state legitimacy in just five years—reveals how quickly criminal organizations can exploit institutional weaknesses to establish parallel governance structures. As El Salvador’s iron-fist security policies gain admirers across Latin America, Salvadorian President Nayib Bukele’s strong public support threatens to normalize the false choice between democratic values and citizen safety.

Countering this trend demands a coordinated international response that transcends traditional security assistance.

First, multilateral development banks should prioritize funding for proven community initiatives, particularly those offering comprehensive youth services that combine education, job training, and psychosocial support.

Second, regional cooperation needs to strengthen civil society networks that can maintain consistent community engagement even during periods of political transition.

Third, international donors should establish dedicated funding streams for local organizations with demonstrated track records of youth intervention while also supporting knowledge-sharing networks across Latin America’s most affected cities.

Fourth, international support must help bridge the gap between immediate security needs and long-term institutional rebuilding. This means funding parallel tracks: robust investment in prevention and reintegration programming and careful support for security sector reform that prioritizes community trust-building over militarization. Successful regional models exist: the aftermath of Colombia’s “false positives” scandal offers valuable lessons in institutional reform. Like its Andean neighbor, Ecuador’s state-civil society rift must be healed, notwithstanding its politically fragmented terrain.

With all eyes fixed on presidential politics, the daily lived experiences of residents on the margins of Guayaquil reveal a stark truth: a hasty embrace of militarization has diverted resources from the vital social infrastructure and economic opportunities that could offer young people genuine alternatives to criminal networks. Time is running out for a holistic approach to security that balances suppression with structural transformation. As organized crime groups demonstrate an unprecedented ability to adapt and evolve their recruitment strategies, the window for corrective action narrows—and nothing short of an entire generation hangs in the balance.

Erin McFee is the founder and president of the Corioli Institute.

Further reading

Thu, Mar 27, 2025

Peru’s crime wave: A populist opening or a chance for reform?

New Atlanticist By Martin Cassinelli

Solving Peru’s security crisis will require institutional reforms that combat political corruption and address the root causes of crime.

Wed, Mar 26, 2025

An ‘America first’ approach to Venezuela is taking shape

New Atlanticist By Geoff Ramsey

US tariff threats against countries importing Venezuelan oil seem geared toward extracting concessions from strongman leader Nicolás Maduro.

Tue, Mar 25, 2025

The US needs to build a new Caribbean policy. Rubio’s trip to the region can be the first step.

New Atlanticist By Wazim Mowla

US engagement with the Caribbean should prioritize energy investments and efforts to reduce violent crime in the region.

Image: A man is placed in handcuffs after being found in possession of drugs during a joint police and military security operation in a low-income neighborhood on the outskirts of Guayaquil, in Duran, Ecuador October 16, 2024. REUTERS/Santiago Arcos