Amid regional turmoil in the Middle East, Iraq’s Federal Supreme Court has faced a crisis of its own.

Last month, six of the nine permanent justices and three of the four alternates submitted their resignations, effectively rendering the court inoperative. The reasons for the resignation requests remain unclear, although some media outlets have suggested that they were in protest against the leadership of Chief Justice Jasim al-Ameiri, a career judge who was elevated to the position of Chief Justice in 2021 and has a reputation for issuing controversial decisions. Others have speculated that political pressure from the executive branch on a prospective ruling concerning the Khor Al-Abdullah treaty with Kuwait may have played a role.

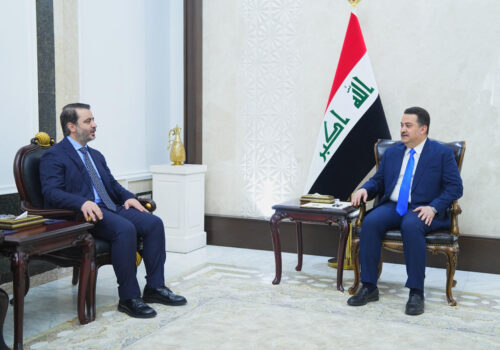

Reports that al-Ameiri was at the center of the mass resignations appeared to have been validated. In recent days, the resigned justices returned to the court after al-Ameiri confirmed his early retirement due to medical reasons. Alternate Justice Munthir Ibrahim Hussein, a career judge formerly of the Court of Cassation, was nominated and confirmed as the Supreme Court’s new Chief Justice.

Regardless of the reasons behind the initial mass resignations, the ongoing uncertainty surrounding the Supreme Court is a serious concern.

The perception, possibly as a result of its eagerness to rule on highly political controversies, that the country’s constitutional court is just another institution that can be politically swayed undermines the very reason for its establishment—to be an impartial arbiter and the lynchpin of the constitutional and political order, not one of its players.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

Since its reconstitution in 2021, the court has played an active and controversial role in shaping Iraq’s political landscape, often drawing criticism from across the political spectrum. Key rulings have included the certification of the disputed 2021 election results, the disqualification of presidential candidates in 2022, the imposition of a two-thirds quorum in parliament for electing the president, and a decision declaring the Kurdistan Region’s oil and gas law unconstitutional.

The court has also weighed in on issues such as budget allocations to the Kurdistan Region and forced the removal of Speaker of Parliament Muhammad al-Halbousi. The court’s September 2023 decision to invalidate the parliament’s ratification of the Iraq-Kuwait treaty concerning Khor Abdullah (the creek between Iraq and Kuwait) ignited a diplomatic crisis, at a time when the Iraqi government was seeking better relations with its Gulf neighbors. (The court was due to rule on a request by the prime minister and the president to reconsider its ruling on the issue.)

This flurry of activity marks a sharp contrast with the court’s prior iteration, whose most publicly significant ruling had been its 2010 decision on which political bloc had the right to nominate the Prime Minister following elections.

Why does this matter?

In the post-Iraq War order, the Supreme Court has arguably served as the only constitutional check on Iraq’s executive power. Successive governments have been formed through broad parliamentary coalitions, and they have been generally aligned with the legislature, leaving few institutional constraints on the executive. That check is especially important in a political system where respect for constitutional and democratic norms has often been lacking. In practical terms, the Supreme Court plays a pivotal role in parliamentary elections (Article 93(7) of the Iraqi Constitution). Election results must be certified by the court, and without such ratification, a newly elected parliament cannot convene, leaving the political system in a constitutional black hole.

While the Supreme Court’s assertiveness over the past few years has brought greater attention to its role, it has also provoked backlash. The court’s expansive approach to jurisdiction has at times placed it at odds with ordinary courts, which fall under the Supreme Judicial Council and are administratively distinct. Because Supreme Court decisions are final and not subject to appeal, the court determines its own jurisdiction without an external check, raising concerns about potential overreach. Critics have accused the Supreme Court of encroaching on political questions and, in some cases, lacking constitutional legitimacy due to its perceived partisan positions.

Problems with the Court

The circumstances that established the Court have also been a cause for its critics to question its legitimacy.

The first Supreme Court was established in 2005 under a law issued by the then-transitional government, prior to the enactment of the Iraqi Constitution. That constitution, which came into force later that year, outlined the framework for establishing a constitutional court in Articles 92–94, including the requirement that a two-thirds majority in parliament pass its enabling law. The rationale behind this supermajority was to ensure the court would have broad political legitimacy and be insulated from future interference by a simple parliamentary majority.

However, two decades on, those constitutional provisions have not been implemented. Instead, in 2021, months before the same year’s parliamentary elections, the 2005 law was amended with broad political consensus, including among factions now critical of the court. The amendment circumvented the constitutional requirements for establishing the Supreme Court while conferring upon it the full powers, word for word, envisioned by the same constitution. This legislative shortcut arguably undermines the court’s legitimacy because it ignores an express constitutional requirement.

At the time, the Supreme Judicial Council and other judicial authorities, as empowered by the amendment to the law, promptly nominated a new slate of justices, and the reconstituted Supreme Court resumed operations. This was seen as a positive step that enabled parliamentary elections to proceed, but the legal and constitutional foundations of the court remain contested.

The way forward

The current crisis underscores the urgent need for a truly independent and competent constitutional court in Iraq—one that can withstand political pressure and command broad public trust. At a minimum, that requires the establishment of a court that meets the constitutional requirements for its formation, thereby insulating the nomination of justices from the ordinary political horse-trading and clearly defining the court’s jurisdiction and interpretive philosophy. That effort should mimic a constitutional conference process and must engage actors outside the political sphere, including lawyers and judges, the academy, and the public at large, to reach a consensus about the role of the Supreme Court and its powers.

The task of establishing an independent supreme court remains extremely hard as the initial steps require consensus by political actors and trust in an institution that will have the power to define the constitutional framework of the state—those same actors have failed to reach broad consensus on less pressing matters.

In the meantime, while the court remains as is, political actors should give the court breathing room to decide on matters independently and without interference, and the court itself should show restraint when delving into political questions.

Constitutional interpretation is a specialized and interdisciplinary task that goes beyond conventional legal training. Justices must be capable of articulating their interpretive methods and applying them consistently. That is especially crucial at a time when Iraq is at a crossroads, facing fundamental questions about revenue sharing, natural resources, decentralization, federalism, civil rights, and international agreements. The country deserves a court that is both equipped and empowered to adjudicate those questions within a framework of constitutional fidelity and institutional legitimacy.

Safwan al-Amin is an international attorney and public policy advisor who counsels corporations and regional governments on legislative and regulatory matters.

Further reading

Mon, Jun 30, 2025

Balancing acts and breaking points: Iraq’s US-Iran dilemma

MENASource By C. Anthony Pfaff

The future of US–Iraq relations is neither as dim as it may first appear, nor as promising as one might hope.

Wed, Jun 4, 2025

Why Iraq should build bridges with its ‘new’ neighbor, Syria

MENASource By

Iraq's position on the Syria transition is split between two camps: the official government, and that of the powerful non-state actors.

Wed, Mar 19, 2025

Why the United States must bridge the Iraq-Syria divide

MENASource By Sarkawt Shamsulddin

With leverage over both capitals, the United States emerges as the linchpin in delicate diplomatic moment between Baghdad and Damascus.

Image: Iraqi President, Abdul Latif Jamal Rashid, attends the swearing-in of the Chief Justice of the Federal Supreme Court, Judge Munther Ibrahim Hussein Iraqi President, Abdul Latif Jamal Rashid, attends the swearing-in of the Chief Justice of the Federal Supreme Court, Judge Munther Ibrahim Hussein, in Baghdad, Iraq, on July 3, 2025. Photo by Iraqi Presidency Office apaimages Iraq Iraq Iraq 030725_IRAQ_IPO_001 Copyright: xapaimagesxIraqixPresidencyxOfficexxapaimagesxNo Use Switzerland. No Use Germany. No Use Japan. No Use Austria