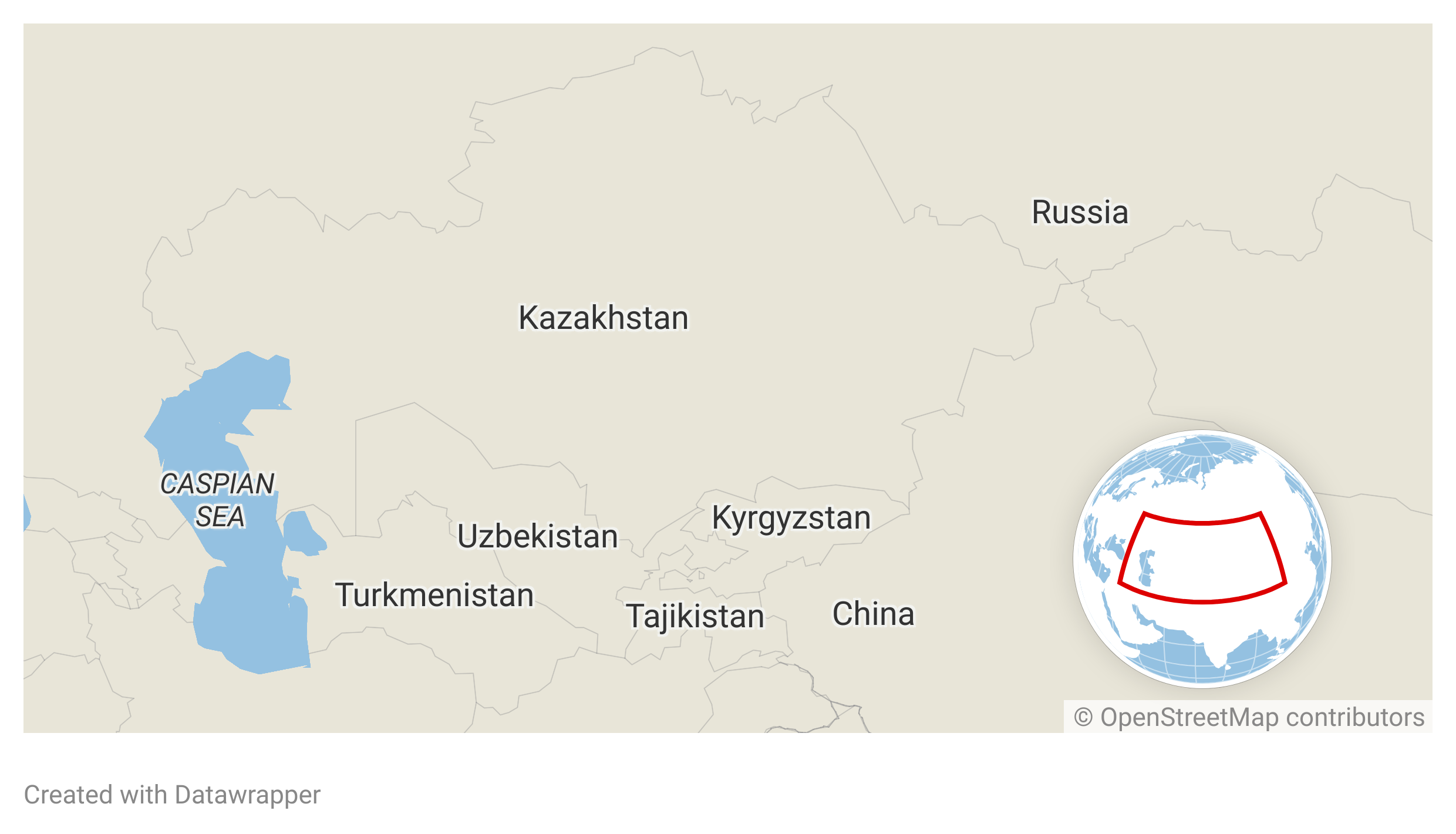

No one knows yet how Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine will end. Already in its fourth year, the fighting and destruction has carried on without either side achieving a decisive victory or stalemate. What is already clear, however, is that Russia’s war has profoundly reshaped global geopolitics far from the frontlines, with significant implications for the five Central Asian states: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

And it could reshape Central Asia’s geopolitics even further. If the war concludes with Russia annexing significant portions of Ukraine, for example, this outcome will certainly influence the competitive dynamics between Russia and China in the region going forward.

How Russia’s war impacts Central Asia

Central Asia’s geopolitical importance stems from its position as a trade crossroads, its vast energy reserves, and its role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For decades, Russia maintained dominance in the region through historical ties, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and the Eurasian Economic Union. However, the war in Ukraine has strained Russia’s regional engagement, creating opportunities for China to deepen its influence in Central Asia—and for local states to leverage their agency to balance these powers.

That does not mean Russia is in a weak position. Despite early setbacks in the war, Russia has adapted, expanding its defense industry to produce up to three million artillery shells annually by early 2025, surpassing NATO’s output. Russian troops have also gained significant combat experience—in contrast to China, whose forces have done little but occasionally repress their own people. Russia’s economy, initially suffering tremendous setbacks due to combined and effective Western sanctions, has shown resilience. The International Monetary Fund estimates the economy grew 3.2 percent in 2024, surpassing the growth rate of many Western economies. This economic resilience is driven by redirected trade to Asia, import substitution, and the growth of Russia’s domestic industries. Russia’s economic and military recovery has bolstered its image as a formidable power in some Central Asian circles, particularly among authoritarian leaders wary of Western pressures to democratize. Russia’s narrative of single-handedly resisting NATO and the European Union (EU) may resonate with some Central Asian elites and the region’s Russian minority populations, enhancing Moscow’s soft power.

However, Russia’s focus on subjugating Ukraine has strained its Central Asian ties. Even if a cease-fire is achieved, Russia’s likely prioritization of consolidating gains in Ukraine and rebuilding its western defenses may limit resources for Central Asia, weakening its ability to counter China’s economic advances in the region. Moreover, some Central Asian leaders, particularly in Kazakhstan, view Russia’s territorial ambitions with concern, fearing similar revisionist moves in regions with ethnic Russian populations, such as Kazakhstan’s north. For instance, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2014 remark that Kazakhstan is an “artificial country” heightened anxieties about Russian intentions, pushing some states to diversify their alignments, most notably toward China. This approach has paid dividends for Kazakhstan: Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged Beijing’s support for Kazakhstan’s “independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity” on a 2022 trip to Astana.

China’s aims in the region

China has capitalized on Russia’s focus on the war to strengthen its foothold in Central Asia. Through the BRI, China has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure, such as pipelines, energy projects, and the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, which bypasses Russia. By 2020, China surpassed Russia as the top trade partner for most Central Asian states.

Russia’s prioritization of its war on Ukraine has also created an opportunity for Chinese arms sales to the region, with reports suggesting that Uzbekistan is set to acquire Chinese fighter jets to replace aging Russian equipment. China’s more than five-billion-dollar investment in Tajikistan’s infrastructure since 2007 dwarfs Russia’s contribution. China’s officially neutral stance on the war in Ukraine and its peace-brokering rhetoric enhance its diplomatic appeal, positioning it as a less confrontational partner than Russia. And Beijing’s financial leverage, through loans and control over infrastructure, further solidifies its influence. For example, China’s role as Uzbekistan’s main gas importer and its investments in renewable energy signal a long-term strategy to dominate the region’s energy sector.

Yet, despite these advances, China faces significant challenges in the region. Central Asian publics’ skepticism toward China, fueled by fears of “debt trap” diplomacy and resentment toward Chinese workers, limits Beijing’s soft power. A seemingly small but telling example of this phenomenon is the fierce backlash in Kyrgyzstan to China flooding the country with cheap, shoddy plastic yurts. The genuine felt yurt, made painstakingly by hand and decorated with women’s hand-embroidered yurt belts, is a source of intense cultural pride among the Kyrgyz. The fact that many are now reduced to buying the Chinese variant due to economic circumstances forces Kyrgyz artisans out of work, fueling anti-Chinese sentiment. On a much larger scale, China’s treatment of the Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang raises concerns in Muslim-majority Central Asian states, potentially undermining trust. These tensions allow Russia to maintain influence, particularly when it comes to security, where its historical ties and CSTO presence remain significant.

How Central Asian leaders approach Russia and China

Central Asian states are not passive in this geopolitical contest. They are active players, leveraging the Russian war to pursue “multi-vector” foreign policies, balancing Russian security ties with Chinese economic opportunities. The war has reinforced this pragmatic approach, as Central Asian leaders navigate Russia’s assertive posture and China’s economic dominance. Central Asian resilience hinges on maintaining internal stability and diversifying its political and economic ties without provoking either Moscow or Beijing. Kazakhstan, for instance, has maintained neutrality on the war while deepening economic ties with China. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have both diversified their energy exports to China, reflecting efforts to hedge against overreliance on any single partner. The United States’ C5+1 summit in 2023 and growing EU engagement with the region offer alternative partnerships for Central Asian states, but Western influence remains limited compared to that of Russia and China.

What will an end to Russia’s war on Ukraine mean for Central Asia?

The situation might well change further if Russia’s war in Ukraine ends or a sustained cease-fire is reached. For instance, if Russia does get away with annexing—or retaining de facto control of—a significant amount of Ukrainian territory, this could enhance its regional power. Selling the Russian war on Ukraine as a victory could encourage greater deference to Russian military initiatives, especially among smaller CSTO member states like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as well as Kazakhstan, which is wary of its vast northern border with Russia.

Moreover, Russia’s strengthened military and economic growth may embolden it to resist China’s encroachment in Central Asia, where Moscow views itself as the historical hegemon. China, prioritizing economic dominance, may tolerate Russia’s security role but push for greater control over trade and resources, potentially straining their alignment and reviving opportunities for Central Asian leverage.

A victorious Russia, perceived as having stood up against the combined might of NATO and the EU, could inspire some Central Asian states to resist Western overtures, indirectly benefiting China’s nonaligned stance. In addition, if sanctions relief comes as part of an agreement to end the war, Russia’s economic dependence on China could decrease. However, if Russia overextends itself after the war, prioritizing the integration of conquered Ukrainian territories over engagement with Central Asia, China could take the opportunity to fill the vacuum, particularly on energy and trade.

Regardless of what a deal to end the war in Ukraine ultimately looks like, the interplay of Russia’s geopolitical ambitions, China’s strategic patience, and Central Asian leaders’ pragmatism will come to define the contested and dynamic postwar regional order.

Tatiana Gfoeller is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and member of the board of directors at American Women for International Understanding. From 2008 to 2011, she served as US ambassador to the Kyrgyz Republic.

Further reading

Mon, Jun 9, 2025

Turkmenistan’s deepening water crisis could have far-reaching regional consequences

New Atlanticist By

Turkmenistan’s water crisis could have significant economic and political ramifications well beyond its borders.

Tue, Jun 3, 2025

How Kazakhstan can anchor a resilient rare‑earth supply chain for the West

New Atlanticist By

By partnering with Kazakhstan on rare-earth element mining, the United States can reduce its dependence on China and build a more secure critical minerals supply chain.

Tue, Apr 15, 2025

Central Asia’s geography inhibits a US critical minerals partnership

EnergySource By

Central Asia holds vast critical mineral resources, but limited export capacity and complex environmental, geopolitical, and legal risks make large-scale US investment unfeasible. The US should instead focus its efforts on allied nations with established mineral export industries.

Image: Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev attends a ceremony welcoming Chinese President Xi Jinping, who arrives to take part in China - Central Asia Summit in Astana, Kazakhstan, June 16, 2025. Kazakh Presidential Press Service/Handout via Reuters.