The expert conversation: Separating signal from noise in Trump’s Ukraine peace plan

Ukraine is facing a “very difficult choice,” President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said today. “Either loss of dignity, or the risk of losing a key partner.” His speech, marking Ukraine’s Day of Dignity and Freedom, came amid reports of increasing pressure from the United States to accept a twenty-eight-point plan to end the war that Russia launched against Ukraine in February 2022.

To dive into the details of the proposal and understand its bigger-picture significance, we turned to John Herbst, the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and a former US ambassador to Ukraine, who always has his finger on the pulse of US President Donald Trump’s efforts to end the war. This expert conversation has been edited and condensed below.

Trump has now given Ukrainian leaders a deadline of Thursday—Thanksgiving in the United States—to respond to a US plan to end the war in Ukraine. That’s presented Ukraine with “one of the most difficult moments” in its history, in the words of Zelenskyy. Is this the pivotal moment that it seems like? And how do you expect Ukraine to respond?

John Herbst

The meaning of this deadline is unclear. In addition to this statement, Trump said that the deadline could slip if there is “positive movement.” It is also true that despite the Kremlin’s rejection of Trump’s cease-fire proposal in August, Trump ignored his own deadline for Russian compliance. There is no reason to assume that the president would severely sanction Ukraine for not quickly accepting a document that appears to have many Kremlin-friendly points.

What do you make of the draft twenty-eight-point peace plan that has been circulating in reports?

John Herbst: I think that some version [of the reported draft]—or similar to that—is being discussed in Kyiv, if not that actual draft.

Security is the principal problem. You have massive aggression by a nuclear superpower against its neighbor. One of the points in the reported draft appeared to suggest giving the Kremlin strategic territory that it has been unable to conquer in over three and a half years of the massive invasion. This would seem to be a fatuous idea, rewarding the aggressor. Then there are the limitations on the Ukrainian military, the victim. Now, it’s true that the points suggest a sizable Ukrainian military of 600,000 people, but that’s still less than the Ukrainian armed forces today and maybe less than they need. The plan also talks about limitations on arms that Ukraine could have. Here too, why are there limitations on the arms and forces of the victim nation and none on the aggressor? So these points are on the negative side. I’m not sure they comport with Trump’s stated objective—which I believe he’s serious about—of achieving a durable peace which leaves Ukraine an independent and secure nation.

On the other side of the ledger, a possible positive is this discussion of US security guarantees. Now, if this phrase turns out to be security guarantees as solid as Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, then that’s a very serious and positive development. The Russians, of course, don’t want that. But if you had a bilateral security guarantee from the United States, like Article 5, that would certainly deter future Russian aggression, because the Russians are afraid of our military, as they should be. After all, they can’t even beat the Ukrainian military, as we’ve seen.

It is worth noting that there is some clarity in the reported draft on the items that work to Moscow’s advantage, but no similar clarity on the security guarantees that are supposed to deter and to protect Ukraine from future Russian aggression.

Obviously, there would have to be true clarity on what that NATO-like commitment means for Ukraine if a deal were to be reached with that as the key security point.

Do you see anything in the draft plans that would prevent Russia from invading Ukraine again?

John Herbst: In theory, Moscow would make a commitment, just like it did in its peace treaty with Ukraine in the 1990s and in the Budapest Memorandum, to respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity. But Moscow’s war on Ukraine and “annexation” of Crimea and other oblasts show Moscow cannot be counted on to meet its commitments.

Zooming out, this war has been going on for nearly four years—nearly twelve years since Russia’s initial 2014 invasion. Why do you think all this activity is happening now?

John Herbst: This is just part of who Trump is and his policy world. He’s constantly in motion, bringing up ideas. He fancies himself a peacemaker. And I say that with respect, because he’s done some remarkable things—from Africa to the Middle East to East Asia. So he’s wondering why he can’t get this thing done [in Ukraine], and his team goes from one idea to another. That, I believe, explains this.

Does the corruption scandal that Zelenskyy is dealing with in Ukraine have any tie-in here?

John Herbst: It’s certainly related. There were clearly Kremlin narratives in the press that Ukraine is losing on the battlefield, [and] Zelenskyy is besieged because of corruption in Ukraine, now’s the time to push him to make concessions. I think those types of narratives demonstrate a misunderstanding of Ukraine. For example, the anti-corruption groups in Ukraine, the civil society folks whom I know well, they’re also the strongest opponents of Kremlin aggression. And if Zelenskyy is weak vis-à-vis them, the worst thing he could do is to make ill-considered, dangerous concessions to Moscow, right? I think there was some wishful Kremlin-type thinking being channeled to American media by people who, in fact, due to their limited knowledge, are all too accommodating of Kremlin aggression.

It wasn’t so long ago that we were talking about a major drone deal between the United States and Ukraine. Trump has helped broker deals for European countries to provide more weapons to Ukraine, plus provided intelligence support. And then we have these latest reports about threats to withdraw US support for Ukraine if it doesn’t sign this peace deal. How do you assess the state of US support for Ukraine in this moment?

John Herbst: One thing we have not heard amid all this sound and fury in the past several days is that the sale of arms and the drone deal are off the table—these are two separate deals, both of great importance. In my understanding, serious negotiations are going on regarding those arms deals. So I don’t see what we’ve seen this week as a rejection of that part of administration policy, but you can be sure that whoever was briefing Axios doesn’t like those deals.

Trump is a mercurial figure. He moves in this direction, in that direction, as he tries to come up with a solution. There have obviously been times when that’s worked for him. I don’t think that works in the current war because Putin’s aim has not changed. He is not going to give up his desire of achieving effective political control of Ukraine. So if a deal along the lines that have been outlined were to go into effect, Putin may lie low for six months, twelve months, twenty-four months before he makes his next move to take additional Ukrainian territory—until either he has a government he wants in Kyiv or he has so much territory that he’s reduced Ukraine to a landlocked, small state somewhere in the western part of its territory.

The only way Trump can be a Nobel Prize winner for ending this brutal aggression is by making sure Putin can’t do that. And that’s ultimately why I think that efforts, including by credulous people who have access to President Trump, to make a deal that enables Putin to achieve his goal are not going to succeed. The only way Trump gets the peace he wants is by making it clear to Putin that he’s going to pay a very high price to continue his aggression.

European partners will now reportedly meet on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Johannesburg to develop their own peace proposal. Do you think that has legs?

John Herbst: Yes. Active European engagement with President Trump has made it much harder for Putin to persuade Trump of something that is against not just Ukraine’s interest or Europe’s interests, but also American interests. Steps like increasing defense spending and a willingness to put European troops on the ground in Ukraine have been important in making it harder for Putin to sell snake oil to the White House. Several European leaders have terrific relations with Trump.

It sounds like you’re saying what we’re witnessing isn’t necessarily the endgame of the war or even the beginning of the end.

John Herbst: We’re really, really, really far from any true endgame negotiation. This is just one more turn of the wheel, and we’re going to have a lot more turns in the future.

There’s clearly a play led by [Russian envoy Kirill] Dmitriev, because of his special relationship with [US envoy Steve] Witkoff, to get a deal that hands over to Russia hard-to-conquer territory in western Donbas and improves relations between Trump and Putin. From Dmitriev’s perspective, the goal is to create conditions that allow Putin to gobble up more of Ukraine—eighteen months, twenty-four months down the road, or maybe right after Trump leaves office. That’s the game. And because the White House does want a deal, which I think is laudable, there are some people playing on that desire to accommodate Russia in ways that undermine American interests in Europe, create an existential threat to the Ukrainian people, and increase the possibility of Russia taking even more provocative actions against NATO allies.

Moscow is conducting ever more serious provocations in Europe—having a MiG [fighter jet] in Baltic airspace for thirteen minutes, having all these drone flights, the sabotage of the railroad in eastern Poland—and NATO has done very little. It’s important for NATO to take serious countersteps to make Russia pay a price for this. President Trump, who considers himself to be a very strong leader, should be taking the lead on that. That’s another way to let Putin know that he cannot simply waltz into the rest of Ukraine.

Say Trump calls you into the Oval: What guidance would you give him? How would you brief him regarding what to do next?

John Herbst: I start by saying, Mr. President, you proved yourself a remarkable peacemaker, but you’re having a hard time on this one, and here’s why: You’ve established a goal which meets American interests. You say you want to create a durable peace by having roughly a cease-fire along the present [battle] lines. In fact, that is a real gift to Putin, because the US is not saying Putin has to withdraw from conquered territory or pay a price for the great evils he’s inflicted on millions of Ukrainians. Still, in an imperfect world, that’s not a bad outcome—if, in fact, you put in place conditions that ensure that Russian aggression is not renewed. The problem you face is Putin does not want that. He wants effective political control of Ukraine. That means he wants to control all of the cities on the Dnipro River, from the north to the south, including especially Kyiv and Odesa. He wants to make sure that Ukraine, as it exists following any peace deal, has no access to the Black Sea. And obviously, if he were to agree to President Trump’s basic concept for peace, he cannot achieve those objectives.

You have to choose what’s more important: a friendly relationship with an aggressor—whose policies are, in fact, adversarial to the United States—or a durable peace. The only way you get [a durable peace] is to make it unpleasant for Putin to continue his war of aggression.

That means you need to send more advanced weapons to Ukraine. That means you have to help Ukraine find a way to finance the war. If you’re not going to send American assistance, okay, but you have these $300-billion worth of frozen Russian assets sitting in the Western financial system. American advocacy of handing those over to Ukraine to deal with its economic needs and to purchase weapons would go a long way. And of course, the sanctions the administration finally put down on Lukoil and Rosneft were excellent, but more needs to come. The administration mentioned after those sanctions that they want to calibrate this. That, frankly, is Biden talk—gradual escalation, which is not the way to persuade Putin to make peace.

Putin thinks, correctly, that he’s outwaited every Western leader in conducting this now nearly twelve-year war of aggression and nearly four-year war of big invasion. And he’s been right. He’s been able to outlast them. He thinks he can outlast President Trump. I think Trump is too smart to allow Putin to do that. Trump has actually made that point in public.

So the administration needs to bring the hammer down on President Putin at the same time it expresses its willingness to have the best relations in the world with him and with Russia once they stop this aggression. Trump was very successful in the Middle East because he was willing to put the hammer on Iran. And until it puts the hammer down on the aggressor in Europe, it’s not going to achieve a durable peace there.

Further reading

Fri, Nov 21, 2025

The good, the bad, and the ugly in the US peace plan for Ukraine

Fast Thinking By

Our experts assess the Trump administration’s proposal for ending the war in Ukraine and what to expect next.

Thu, Nov 20, 2025

Any serious Ukraine peace plan must address Putin’s imperial ambitions

UkraineAlert By

The new US plan to end the war in Ukraine fails to recognize that Putin is not driven by limited political goals. He believes he is engaged in an existential struggle to revive Russia’s great power status and will never accept a compromise peace, writes Mykola Bielieskov.

Mon, Oct 27, 2025

Trump’s place in history depends on his approach to the CRINK

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

After a string of foreign policy wins, Trump's more significant challenge lies ahead: countering the bloc of China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

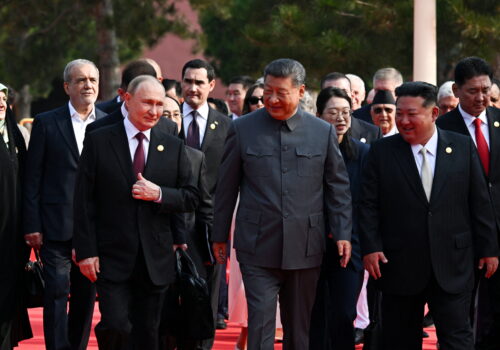

Image: Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskiy and his wife Olena attend a commemoration ceremony at a monument to the so-called "Heavenly Hundred", the people killed during the Ukrainian pro-European Union (EU) mass demonstrations in 2014, to mark the 12th anniversary of the start of the uprising, amid Russia's attack on Ukraine, in Kyiv, Ukraine November 21, 2025. Ukrainian Presidential Press Service/Handout via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY.