African countries prepare for a coronavirus pandemic

Since its detection in Wuhan at the end of last year, the novel coronavirus called COVID-19 has claimed more than 2,500 lives and has infected over 80,000 people across forty-seven countries (at the time of publication). Of those countries with confirmed cases, only two are in Africa: Egypt confirmed the continent’s first case on February 14, 2020, while Algeria confirmed its own on February 25. By now, at least 25 other African countries have alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) of suspected cases, but all are either pending or have resulted in negative tests – a remarkable fact, considering the strong integration between the African and Chinese markets. Given the alarming rate at which COVID-19 is spreading, it was always only a matter of time until the pandemic reached Africa. Now that it has, how prepared are African governments to contain it?

They aren’t. Due to the nature of the virus – the disease’s long incubation period, asymptomatic transmission, and the number of false negatives associated with the testing – health officials across the developed world have declared that a global pandemic is inevitable. Bill Gates recently made headlines by predicting that the outbreak could cause 10 million excess deaths worldwide. That prediction is certainly premature – far too little is known about the virus’ deadliness and how it may evolve over the next couple of months to estimate how many people it may or may not kill. What is abundantly clear, however, from the influenza-like contagiousness of this illness, is that delaying the spread of the illness and buying time for preparation is the best that nations can hope to accomplish.

Fortunately, many governments of African countries have already proactively implemented preventive measures. As soon as the virus emerged, the WHO rapidly identified thirteen priority countries in Africa (Algeria, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia) that it considers at greatest risk of acquiring the virus, due to their established direct links or frequent travel to and from China. The WHO has already intensified inter-governmental coordination and communication with each of these countries’ ministries of health.

And at the country-level, authorities have amplified screening procedures at airports. These methods range in effectiveness: in Côte d’Ivoire, the government has installed thermal imaging cameras at the airports, while in South Africa the Minister of Health has opted for non-invasive but less-effective thermometers. In Nigeria, the government has also issued a travel advisory, warning citizens to postpone any travel arrangements to China, unless “extremely essential,” until the virus is better contained. In Mozambique, visas are being blocked for visitors from China.

Most usefully, a majority of African airlines—including Kenya Airways, South African Airlines, Rwandair, and Royal Air Maroc—have all suspended direct flights to China, thereby limiting the risk that an infected passenger will disembark and spread the virus. (Most Western nations – including the United States – have also adopted travel restrictions on visitors from China.)

Unfortunately, the effectiveness of African efforts to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus is likely to be undermined by Ethiopia, whose national carrier, Ethiopian Airlines, is controversially continuing to provide direct service to and from mainland China. The continuing arrival of visitors from China dramatically increases the likelihood that travelers through Ethiopia’s Bole International Airport will be exposed to the virus – and Bole’s status as an international hub could transmit that risk to the entire continent, and beyond. (An estimated 20,000 persons transit through Bole daily.) Ethiopian Airlines’ chief executive officer, Tewolde Gebremariam, has assured the press that Bole is taking maximum precautions, but this has done little to satisfy doubts.

One false negative from an individual infected with coronavirus but showing no symptoms and the spread could become uncontrollable. Each infected individual has the capability to infect between 1.5 and 3.5 people. Worryingly, until very recently most African health laboratories lacked the proper equipment to test these samples. At the beginning of February only Senegal and South Africa were capable of providing the necessary results, but as a result of WHO recommendations the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention have successfully increased this number to 27.

Some African countries – including Nigeria, Senegal and Mali – have demonstrated strength and resilience in past efforts to combat the Ebola virus. But other nations which did struggle – among them Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and the Democratic Republic of Congo – are evidence of the particularly fragile health care systems around the continent. Pre-established isolation facilities that were created to combat the Ebola crisis may prove to be crucial assets in containing the spread of coronavirus, but only if cases are detected and traced early enough to prevent widespread transmission. Unfortunately, the presence of porous borders, the continuous flow of often unregulated travelers, conflict, and congested cities and slums, make early detection much harder to achieve.

The virus has so far been slow to find its way to Africa. As of publication, there have only been two confirmed cases on the continent (in Egypt and Algeria). But reports of potential cases are proliferating: in Zambia, for example, employees at a Chinese-run hospital reportedly witnessed returnees from China check into the facility with symptoms of fevers and coughs who were neither isolated nor tested for coronavirus. The Zambian health ministry has refuted those claims and has promised to publicly declare any confirmed cases of coronavirus. Generally, however, it is difficult to distinguish legitimate reports of misconduct from deliberate misinformation and fear-mongering, both of which are starting to proliferate on Twitter.

It’s too early to predict how COVID-19 will affect Africa. While the case fatality rate has not been officially determined, it is thought to be around 2 percent. A recent study published in a medical journal revealed that the average age of a coronavirus patient is 55 years old, and that 80 percent of those who have died from the disease were aged sixty or above, the majority with preexisting health conditions. Youths appear to be far less susceptible to the disease and less likely to require hospitalization when they do contract it. If youths are truly less vulnerable to COVID-19, African nations, with a median age of only nineteen, may well not experience anything like the devastation that has occurred in the disease’s epicenter of Wuhan. Indeed, this global crisis could prove be a powerful example of Africa’s demographic dividend in action.

Regardless of the virus’ physical toll, the economic shock of the crisis is likely to be severe. The World Bank estimated an overall loss of $2.8 billion to the GDPs of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, as a result of the 2014 to 2016 Ebola epidemic. A major source of revenue for many African countries comes from tourism, which is likely to be hit hard by the flight cancellations and the climate of fear surrounding the outbreak. (In 2014, even countries that were geographically distant from the Ebola outbreak experienced a precipitous decline in tourism.) Economists are already predicting a $62 billion loss in growth to the Chinese economy, which will no doubt have significant implications for the African countries with whom China is a major economic partner. With so much at a stake, the hope is that COVID-19 will never spread throughout the continent. But the necessity for preparedness cannot be overemphasized.

Joanne Chukwueke is an intern at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

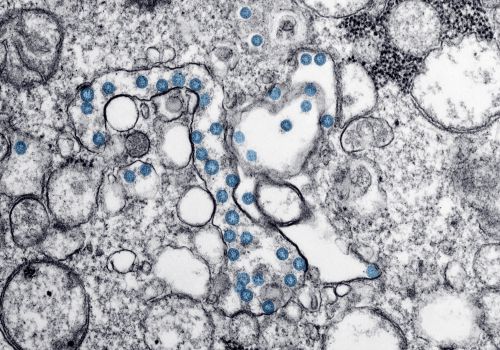

Image: Spread of COVID-19 demands health workers use protective gear. (Pixbay)