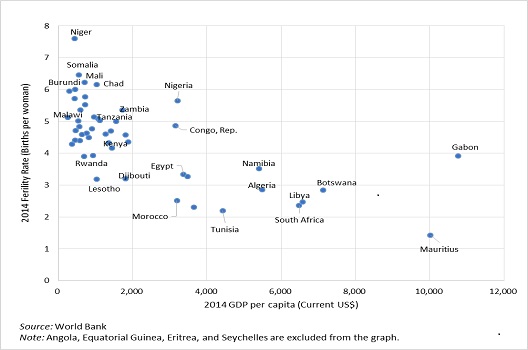

As the global downturn in commodity prices and the decreasing demand and investment from China begin to stymie Africa’s historical drivers of economic growth, one of the continent’s largest potential assets—its workforce—is taking off. Africa’s high fertility rates are leading to a demographic shift that will have profound consequences for the region’s long-term economic outlook.

As the global downturn in commodity prices and the decreasing demand and investment from China begin to stymie Africa’s historical drivers of economic growth, one of the continent’s largest potential assets—its workforce—is taking off. Africa’s high fertility rates are leading to a demographic shift that will have profound consequences for the region’s long-term economic outlook.

While many other regions of the world are aging, Africa’s population is becoming increasingly youthful. Africans under the age of 25 currently make up 60 percent of the continent’s population and, as fertility rates fall elsewhere, larger proportions of the global workforce will be African. By 2035, the number of Africans reaching working age will exceed the rest of the world combined. Looking longer term, the consequences are even more dramatic: by the end of this century, the United Nations predicts that the world will be home to more Nigerians than Europeans.

This demographic shift comes with big challenges. The African countries whose populations are growing most quickly also tend to be the poorest. Governments already struggling to provide access to health care, education, and infrastructure face an uphill battle against high fertility rates and the increasingly larger cohorts of citizens demanding services. Failure to provide opportunities for this growing segment of the population could easily become a burden for sluggish economies or a source of political instability. What’s more, young Africans who lack access to employment at home will look for it elsewhere, robbing their country of origin of its engine for economic growth. “Brain drain,” in particular, continues to sap the continent of many of its most highly skilled workers. In 2013, an estimated one in nine Africans with a tertiary education were living and working in developed nations elsewhere.

However, the demographic prognosis isn’t all bad. If Africa is able to manage its population growth by controlling fertility rates as much as possible, and adequately invest in the human capital of these new generations, the continent’s increasingly large workforce will be one of its largest assets. Harnessing Africa’s demographic dividend means translating population growth into economic growth, a process that will require creating sustainable jobs that can absorb the growing echelons of young workers. If Africa is able to create productive employment for its youth, the potential is immense. For example, between 1990 and 2010, 75 percent of the continent’s gross domestic product per capita growth was a result of the expanding workforce. Further investment in labor-intensive, value-added industries, such as manufacturing, will capitalize on this powerful driver of economic growth.

Once employment opportunities are created, protecting these jobs from fluctuations in the global markets and, in particular, from external shocks, will be paramount. This protection requires transitioning economies away from a dependency on commodity exports and towards a diversified array of trading partners and products. Certain countries, such as Morocco, have already made substantial progress in terms of economic diversification—no product exported from Morocco makes up more than 10 percent of the country’s total exports.

The emergence of a larger consumer market will also present commercial opportunities to the growing number of African firms. Total consumer spending in Africa already surpasses that of Russia, matches that of India, and is projected to double over the next 5 years. Over the long term, the opportunities will be massive—the number of African middle class consumers is expected to increase to 1.1 billion by 2060, most of whom will be living in cities. The continent stands to significantly benefit as more African companies rise to meet this growing demand.

Finally, though “brain drain” remains a significant challenge, some African countries have begun to recognize the potential of returning diaspora members, who can bring the skills and capital acquired abroad back to their country of origin. Ghana, in particular, has actively encouraged return migration since 2001 with the A Right To Abode Act, which gives members of “African descent in the diaspora” the right to live and work in the country. And African diaspora members are becoming more receptive to the idea; according to a 2010 International Organization for Migration report, around 70 percent of East African migrants living in the United Kingdom are willing to permanently return to their country of origin.

If properly managed, Africa’s young and growing workforce can help the continent overcome the challenges presented by low global commodity prices and China’s economic slowdown, and serve as a strong driver for economic growth in the coming decades. For more on how African economies can maintain steady growth in this constrained economic environment, see a new Atlantic Council study by J. Peter Pham and Aubrey Hruby, Embracing Impact: How Africa Can Overcome the Emerging Market Downturn.

Julian Wyss is a Program Assistant with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and Erina Iwami is an Africa Center intern.

Image: Ex-combatants receiving technical training in Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire, (UN Photo/Abdul Fatai)