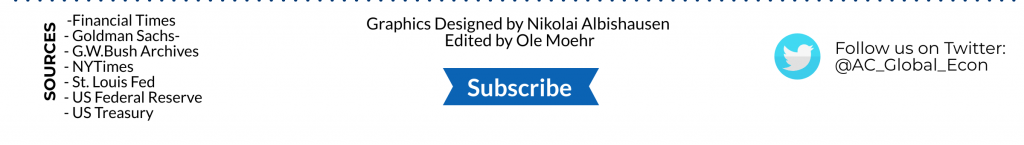

The economic shock delivered by the coronavirus is set to plunge the world economy into the second recession in a generation. Judging by US economic indicators, such as the record 3.3 million jobless claims for the week of March 15-21, the current crisis might eclipse the economic damage caused by the global financial crisis which lowered US gross domestic product (GDP) by 5 percent, eliminated almost 9 million jobs, and destroyed $19.2 trillion in household wealth. Inspired by an Atlantic Council panel discussion featuring former CEA Chair Jason Furman and other high-level experts, this edition of the EconoGraphic compares the US policy response to the financial crisis and the coronavirus shock. The graphic assesses the economic harm done so far and contrasts the measures taken by the Federal Reserve (Fed), Congress, and the G20 in response to both crises.

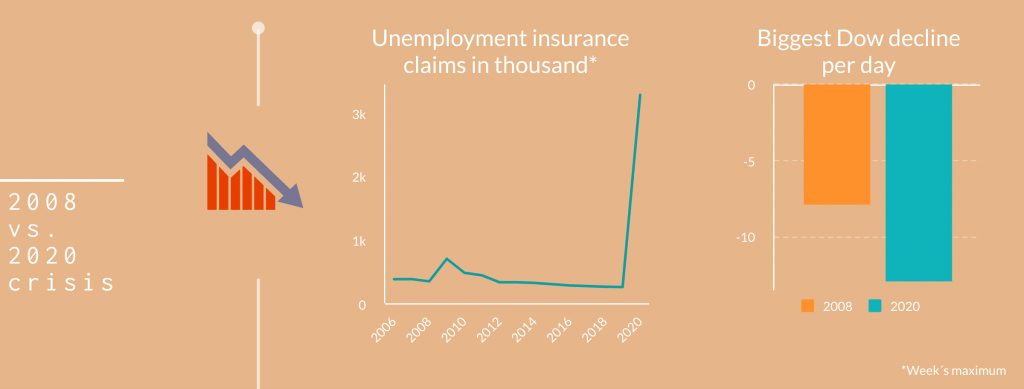

To calm markets and provide liquidity to key market participants, the Fed initially followed its own blueprint from the financial crisis by lowering the key interest rate to zero and announcing a $700 billion quantitative easing program. Signaling the importance of quick, decisive action against this severe exogenous economic shock, the Fed moved beyond its 2008-9 playbook last week by committing to expand purchases of US treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities “as needed with no pre-determined limit.” The Fed’s decision to provide “unlimited” quantitative easing is a marked difference to the financial crisis. Additional novel measures by the Fed include setting-up a special purpose vehicle that will use $30 billion in equity funding from the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund to provide direct bridge financing to healthy US businesses. Finally, the Fed announced a plan to support small and medium sized enterprises via a new “Main Street Business Lending Program” to underscore its commitment to provide support to the American economy as a whole.

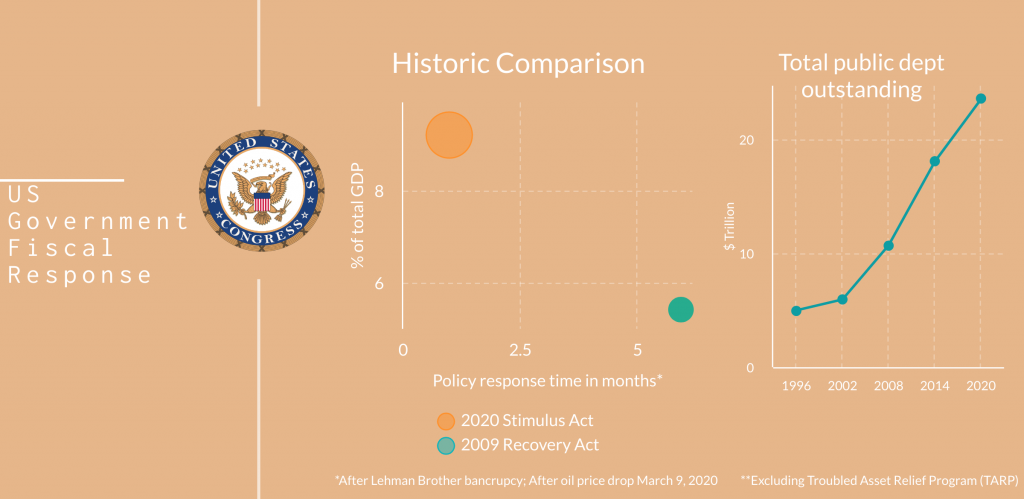

Our graphic detailing Congress’ fiscal stimulus bill highlights the greater speed and magnitude with which US lawmakers responded to the coronavirus shock compared to the financial crisis. After the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which Congress enacted in 2008, failed to stop the downward spiral of the US economy, Congress acted again in early 2009 by passing the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to stimulate the economy. This time Congress moved more swiftly to pass the $2.2 trillion CARES Act in a few weeks after the outbreak of the crisis. The legislation focuses on helping the consumption driven American economy to survive until the spread the of the coronavirus is contained and the economy can recover. As a first and in contrast to the ARRA, US households will receive direct cash payments. US adults earning less than $75,000 will receive a one-time payment of $1,200 and families will receive $500 per child. In addition, Congress is bolstering unemployment insurance, providing $377 billion to support small businesses, and earmarked $500 billion for large companies from troubled sectors such as airlines. $425 of these $500 billion will be used to guarantee loans from the Fed to companies that would otherwise not be able to access credit markets. Congress had to act – and might have to act again, if the coronavirus remains out of control – to extend a lifeline to the American economy. Nonetheless, we believe US policymakers must address the fast-rising public debt, once the economy is recovering, to ensure that the US government continues to have appropriate fiscal firepower at its disposal to react to future economic shocks.

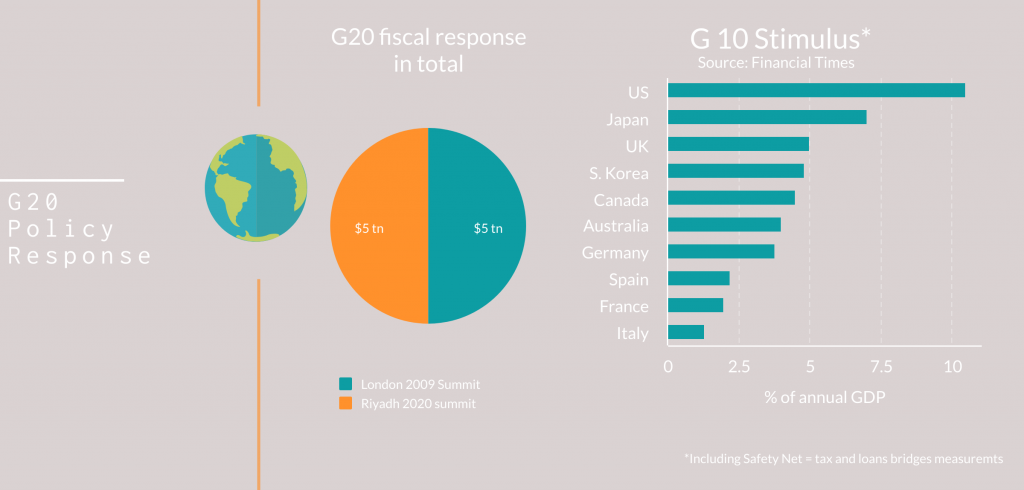

In a sign of the times, the coordinated fiscal response at the G20 level has fallen short of expectations by only matching the $5 trillion total dollar commitment during the financial crisis. In 2009, $5 trillion equaled 2% of G20 countries’ GDP. Our assessment, outlined in a recent Atlantic Council piece by our senior fellow Hung Tran, is that the coordinated G20 “fiscal measures need to be much larger—probably doubling the previous effort [during the financial crisis] if not more.” Most developed countries’ much higher public debt burdens as a result of the financial crisis might constrain policymakers in their attempts to marshal greater resources for stimulus spending to fight the economic crisis triggered by the coronavirus.