Funding the European defense surge

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine reminded Europe of the ever-present threats to its security and propelled defense to the forefront of European Union (EU) priorities. Governments reacted swiftly: in 2021, only four EU member states met the 2 percent gross domestic product (GDP) defense spending benchmark of NATO. As of July 2024, that number has surged to sixteen. Countries are clearly eager to reshape their budgets to boost defense spending.

While the EU has taken important steps toward solidifying its strategic compass, as well as strengthening its defense industrial base and common defense funding, it remains a nascent defense actor. It’s difficult for Europe to build out a common strategy and properly fund common defense projects when member states not only have individual national defense priorities, but disagree on the usefulness of common funding at all. Consequently, European unity on defense hinges not only on political will, shared strategy, and the readiness to act collectively, but also on decisions about funding.

In order to bring the European Defense Union to life, EU institutions and heads of state must recognize that economic and industrial policies can lead to effective defense cooperation. The European Commission appears to be in favor of such a strategy. Spearheading this effort is the European Defense Industrial Strategy (EDIS). EDIS aims to enhance defense industrial readiness across EU member states by promoting coordinated investment, joint research and development, synchronized production, collective procurement, and shared ownership of defense assets within Europe. This strategy seeks to bolster strategic autonomy and reduce reliance on non-EU suppliers, ensuring that Europe can independently meet its defense needs. Additionally, there are significant comparative advantages and benefits from a Europe-wide division of labor in the defense sector.

Joint procurement is a key priority for EDIS because it promotes collaborative investment and fiscal savings, which would lead to purchasing economies of scale and more effective allocations of defense budgets. Recently, member states indicated a willingness to cooperate with the Commission to combat the surge in wildfires with the joint order for purchasing Canadair DHC-515 water tankers. The funding structure consists of a hybrid approach, with orders to purchase the tankers placed by both the EU and individual member states. The size of the order achieved purchasing economies of scale, leading to a much more competitive purchase price.

The EU has already begun utilizing joint procurement to solve its fractured landscape of military equipment and defense systems. The European Peace Facility (EPF), off-budget funding mechanism, was used to oversee the approval of funding of military equipment for the Ukrainian Defense Forces. This success should be built upon to reach a more efficient system of procurement across the board. EDIS guidelines suggest that member states procure at least 40 percent of defense equipment collaboratively by 2030. Indications show that joint procurement could increase savings by up to 30 percent.

Another area for improvement relates to targeted multinational investment in the EU defense industry. Leveraging resources from the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) €550 billion pool of funds can significantly upgrade the EU’s defense capacity and innovation. Traditionally, the EIB was restricted by its statutes to funding any defense initiative apart from certain dual-use equipment. However, this past May, the EIB Board of Directors endorsed the Eurogroup’s Action Plan for Security and Defense, adapting its lending policy to expand the definition of dual-use equipment, such as drones, and “to open its dedicated SME credit lines to companies active in security and defense”, therefore allowing the direct funding of such dual-use tools.

Despite their significance, however, joint procurement and increased EIB financing cannot cover the preexisting investment gap in Europe’s defense capabilities. Between 2009 and 2018, member state cuts amount to an aggregated underinvestment of around €160 billion, compared to the 2008 spending level. Given the changing attitude of governments and EU financial institutions, formulating an equitable funding model remains a pivotal challenge. While straightforward and aligned with each country’s ability to pay, a simple GDP-based approach may generate resistance from wealthier nations that could feel burdened by disproportionately high contributions relative to their needs and may bear public backlash. This challenge is also preventing further talks surrounding a recovery fund specifically for defense. Joint borrowing, proposed by Spain, France, and Belgium, aims to build on the €800 billion joint debt to tackle the challenges of COVID-19. This proposal has already ignited negative reactions from more fiscally conservative member states.

A more sophisticated model that adjustsfinancial contributions to a joint investment fund or other funding structure based on strategic priorities could address these concerns by increasing buy-in from countries with heightened security risks, such as Greece and Poland, two countries with a high percentage of defense spending. However, this model’s complexity and potential disputes over threat assessments make its implementation challenging. Hybrid models of mandatory and voluntary contributions are another possibility, offering flexibility and ensuring a baseline of collective action tailored to specific security challenges.

In any case, robust governance mechanisms will be required to ensure efficient resource use and avoid duplication with NATO efforts. The success of any funding model depends on clear strategic objectives, robust oversight, and the political will to transcend national differences for collective security.

Overall, to properly improve the European defense industry it is key to incentivize European defense firms to raise their level of investment in new capacity to achieve economies of scale and lower unit costs. The creation of a bigger European defense market, coupled with increased official financing through national funds, incentivizes higher research and development activity and a stronger drive for increased production efficiency to gain market shares in a growing market. These provide incentives for increased start-up and merger and acquisition activity. This, coupled with a strategy to integrate more European firms into the supply chain of the European defense industry and higher political coordination in identifying and pursuing common defense needs, could establish a European market where member states enjoy lower prices per unit and priority service. Moving forward, the harmonious cooperation of the public and the private sector, under more coordinated political oversight, could transform Europe’s defense capabilities.

Konstantinos Mitsotakis is a former Young Global Professional at the Atlantic Council’s Geoeconomics Center.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Thu, Sep 12, 2024

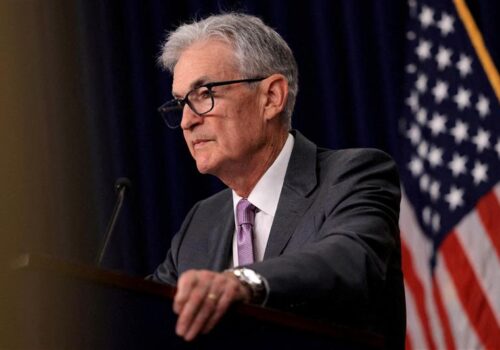

It’s not too early to start grading Jerome Powell’s historic tenure

Econographics By

Jerome Powell's legacy hinges on his bold monetary actions during crises and how effectively these interventions will be unwound in the future.

Fri, Sep 6, 2024

The problems with the IMF surcharge system

Econographics By Hung Tran

The IMF's surcharge system is doing more harm than good for borrowing countries and its justifications are facing new questions.

Thu, Aug 22, 2024

Why the next trade war with China may look very different from the last one

Econographics By Mrugank Bhusari

Far more countries share concerns over the impact of an expansion of Chinese exports. This time, they will likely target finished consumer goods over intermediary inputs.

Image: Vilnius, Lithuania - February 16 2022: Flag of NATO, European Union and Ukraine waving together in the sky