This year’s town hall on climate change gave leading Democratic candidates a chance to discuss their climate policy proposals in detail, on a national stage. One of the most notable policies put forward is the idea of putting a price on carbon. The New York Times noted that “in perhaps the most significant development of the night, more than half of the 10 candidates at the forum openly embraced the controversial idea of putting a tax or fee on carbon dioxide pollution.” The Times added that a carbon tax “has been considered politically toxic in Washington for nearly a decade.” Or, in the infamous words of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign chairman, “we have done extensive polling on carbon tax. It all sucks.” This is the first in a series of three blog posts that addresses carbon pricing; first, by addressing the political feasibility of carbon pricing proposals; next, by looking at how corporations have chosen to incorporate the cost of carbon into their investments; and finally, by imagining the impact of a carbon pricing scheme on manufactured products and consumers.

The Democratic discourse on climate—as on other issues, most notably health care policy—seems to have shifted dramatically since 2016, to the point where carbon pricing is accepted within the mainstream, especially to candidates who see it as a way to fund the development of renewable energy and to “impose a tax on corporations.” A few current and former Democratic candidates are “agnostic on whether [a carbon price] should be a tax or cap-and-trade.” A carbon tax would be technology-neutral and would ensure that any energy source that produced carbon would be more expensive. However, several Democratic candidates have indicated their preferred technologies; for example, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) have both spoken extensively about their commitments to renewables. Sanders was a co-sponsor of the 2017 “100 by ‘50” Act, which calls for 100 percent renewable energy in the United States by 2050, and in August stated, “I think we’ve come farther than [a carbon tax] . . . It’s not an essential part of what I believe has to happen.” To complicate matters more, a few candidates seem to conflate the terms “clean” and “renewable.” Warren, for example, has called for “‘all-clean, renewable, and zero-emission energy’ by 2035.”

However, the slow shift among DC policy makers in support of a carbon tax may be recent, but it began well before CNN’s town hall event. The 45Q tax credit, which is considered by some observers to be a method of carbon pricing since it incentivizes carbon capture, was expanded in 2018. Jason Ye, from the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), wrote a factsheet in August 2019 that compares eight carbon pricing proposals put forward by Democrats and Republicans in the 116th Congress. Ye provides an extremely useful analysis of the differences between the proposals, which include variations on the point of coverage (e.g., upstream or midstream), the starting level of the tax, and the rate at which it increases. The proposals also differ slightly in the types of substances that they cover (e.g., carbon dioxide emissions from gasses, fuels, industrial products, or processes). Most of the carbon pricing proposals are for a carbon tax, although the Healthy Climate and Family Security Act proposed by Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) and Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA) is a cap-and-trade proposal.

However, the difference in carbon price proposals that is likely to cause the most contention is the question of what to do with the revenue created by the tax. We have seen this play out in Washington State (interestingly, under the watch of Governor Jay Inslee) in the last two election cycles. On the one side are Republican proponents of a carbon tax, under the condition that it be” revenue-neutral (accomplished in the 2016 Washington State Ballot Initiative 732 by returning the revenue as “cuts in other taxes” or, in proposals like Baker-Shultz and the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, through returning “all of the tax revenue to American households in the form of monthly rebate checks”). Democrats generally favor a revenue-positive carbon tax, in which revenue goes towards investments; in the case of Washington’s 2018 Ballot Initiative 1631, carbon tax revenue would have gone towards “$1 billion per year in clean air, water, energy, and communities.” Despite their differences—meaning that at least one of them should have garnered enough support—neither I-732 nor I-1631 was able to pass.

There is a growing political acceptance of carbon pricing, both on the Hill and among presidential hopefuls. However, carbon pricing is by no means inevitable, as Washington State’s failed ballot initiatives demonstrate. As Democratic candidates continue to articulate their climate and energy policies, it will be important to track whether they are favoring carbon pricing or renewables mandates, and whether they incorporate all low-carbon technologies in their discussions of “clean” energy.

Dr. Jennifer T. Gordon is deputy director of the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. You can follow her on Twitter @JenniferThea11

Related content

Subscribe to the Global Energy Center newsletter

Sign up to receive our weekly DirectCurrent newsletter to stay up to date on the program’s work.

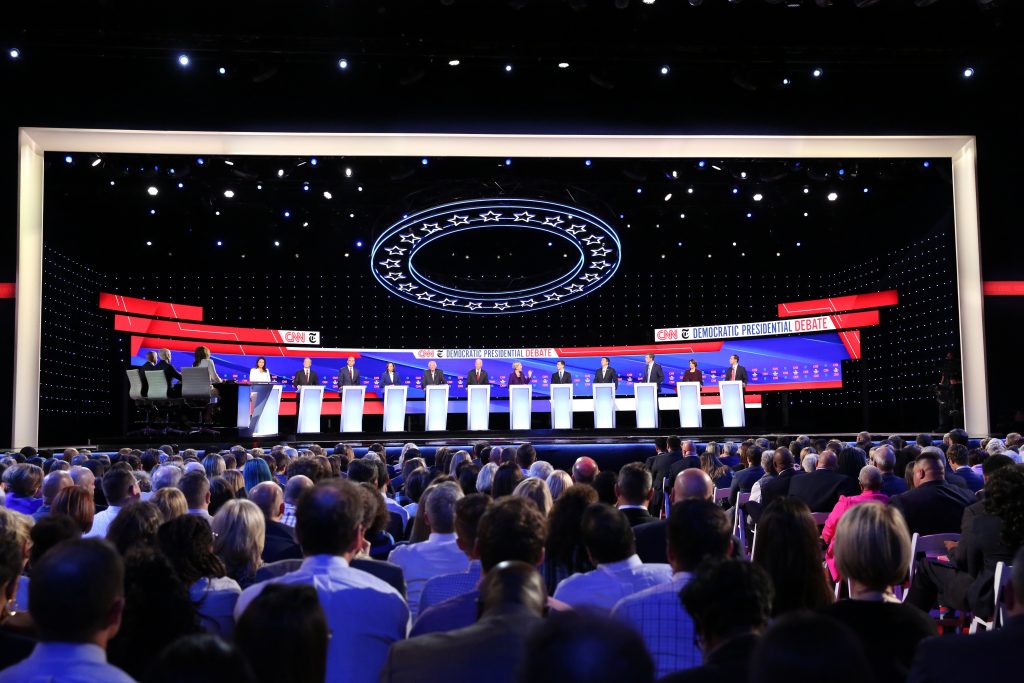

Image: Twelve Democratic US presidential candidates debate during the fourth US Democratic presidential candidates 2020 election debate at Otterbein University in Westerville, Ohio, October 15, 2019. REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton