Iran is having nationwide protests. Is it a ‘revolution’?

The brutal killing of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a young Iranian woman, at the hands of the “morality police” of the Islamic Republic, has sparked widespread protests, with Iranians chanting anti-regime slogans for more than two weeks. Unlike previous protests, the ongoing demonstrations are seemingly much more widespread, with all thirty-one provinces experiencing protests, including the bastions of Shia clergy, Mashhad, and Qom. The Islamic Republic, as usual, has responded by severely limiting access to Internet, arresting hundreds of students and political activists, and killing more than fifty people, according to some reports.

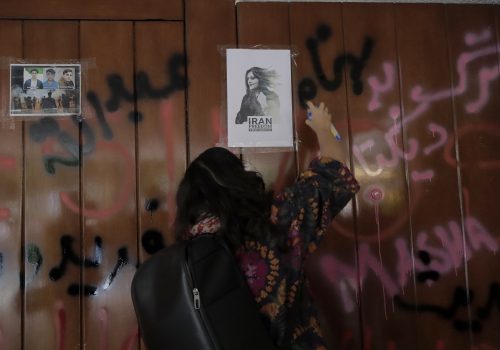

A number of factors distinguish these protests. First, is the leading role of women. While Iranian women—dating back to the Tobacco Movement of 1886, the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, and the Islamic Revolution of 1979—have historically played a significant role in Iran’s protest movements, this time around, they have taken center stage in the demonstrations. Further, is the significant presence of the younger generation, which does not identify with the ideals of the Islamic Revolution. This generation did not participate in either the revolution of 1979 or the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), and seeks fundamental changes in political and social spheres.

Additionally, many celebrities, athletes, and political figures have openly expressed their solidarity with the demonstrators. For example, Ali Daei and Ali Karimi—two legendary soccer players of the 1990s and early 2000s—Asghar Farhadi, the prominent Iranian film director, and a number of other artists have condemned the killing of Amini and the subsequent crackdown on protestors, further expressing their support for the rightful demands of the people.

Meanwhile, international celebrities, activists, and even the hacktivist group Anonymous, which has claimed to have attacked Iranian government websites and state TV, have come out in support of Iranian protestors. The United States, meanwhile, issued a General License that eased some sanctions on the export of information and communication technologies to Iran, prompting billionaire tech entrepreneur Elon Musk to express his own support by offering to “activate” the Starlink satellite internet connection to help Iranians evade government censorship. President Biden has further promised to “look for ways to facilitate technology services” to Iranians.

Despite the widespread protests and international support, one has to be cautious in predicting the outcome. While some commentators have gone so far as to call the demonstrations a “women’s revolution,” this seems to go too far—at least for the time being. In his analysis of the French Revolution, Alexis De Tocqueville identified a political revolution as a “sudden and violent revolution that seeks not only to establish a new political system, but to transform an entire society, and slow but sweeping transformations of the entire society that take several generations to bring about.”

Meanwhile, political scientist Patrick O’Neal identifies a revolution as a form of “political violence” and the “public seizure of the state in order to overturn the existing government and the regime.” The current demonstrations in Iran do not match these definitions, although people are chanting against Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his dictatorship. Rather, they seem to be more of a strong outcry for justice. Additionally, the demonstrators have not pursued the seizure of the state.

Another key ingredient for revolution is missing. So far, the security forces of the Islamic Republic remain intact, and the state has continued to rely on the Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) and plainclothes agents to crack down on protestors. Meanwhile, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), which is tasked with protecting the revolution from internal and external threats, has not been deployed, perhaps because the state feels secure enough without it.

During the 1979 revolution, the conventional army, or Artesh, and Imperial Guard, which were tasked with protecting the monarchy and the state, collapsed even before the Shah departed Iran and were unable to protect the former regime. One should also keep in mind that, at the time of writing, major cities—including Tehran, Mashhad, Tabriz, and Shiraz—remain completely in the control of authorities, despite witnessing large demonstrations and clashes with security forces. There have also been some reports of a strike, but they are not widespread nor has there been the closure of the Tehran bazaar, which characterized the Islamic revolution.

Last, but certainly not least, there is a lack of viable political alternatives. Opposition to the Islamic Republic is either weak or fractured—irrelevant or rejected by most of the people of Iran. Two major groups bear mentioning here. Supporters of the monarchy contend that Reza Pahlavi, the son of the ousted Shah, is the legitimate leader for the future of Iran and point to the pro-monarchy chants of people inside Iran as evidence. However, the Crown Prince himself announced in 2021 that he “personally” prefers a republican system, which casts serious doubt over his willingness to take back the Peacock Throne. The situation is even worse for the Mujaheddin-e Khalq (MEK), which is widely despised by Iranians of all political stripes because of their siding with Saddam Hussein when Iraq invaded Iran during the 1980s.

In the absence of a strong leader accepted by the majority of opposition groups, it is unlikely that the current demonstrations will lead to fundamental change. If the demonstrations continue and expand, the regime will likely employ even more security forces wielding even more brutal tactics. Additionally, as long as security forces, especially the IRGC, remain intact and loyal, the regime will likely survive. At this stage, there is no evidence that the IRGC is abandoning the regime and the Artesh has remained neutral. Hence, the most likely scenario is that the regime, in order to calm the situation, implements some minor reforms, and the protests will peter out over time. In this context, Raisi, while addressing the widespread protests in the country, told Iranian State TV that some reforms in the “implementation” of laws may be necessary.

Notwithstanding this situation, the Islamic Republic faces a serious crisis of legitimacy, as it has been unable to deliver on any of the promises of the revolution. Iranians lack political and personal freedom as well as prosperity and independence from foreign powers.

Iran was the first country in the region that witnessed a revolution to limit the powers of a monarch and give the people a voice in their governance. The 1979 revolution, too, claimed to offer self-representation for Iranians, only to be manipulated by authoritarian clerical rulers. Perhaps, for Iran, the path to democracy “zigs and zags” and sometimes “moves in ways that some people think is forward and others think is moving back,” or so said former President Barack Obama about the United States in November 2016.

Sina Azodi is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council and a lecturer of International Affairs at the George Washington University’s Institute for Middle East Studies. He is also a PhD Candidate in International Relations at University of South Florida. Follow him on Twitter @Azodiac83.

Further reading

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Tue, Sep 27, 2022

How to turn Iran’s moment into a movement

IranSource By Borzou Daragahi

In Iran, the momentum is there. It just needs direction and a helping hand.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Image: A man gestures during a protest over the death of Mahsa Amini, a woman who died after being arrested by the Islamic republic's "morality police", in Tehran, Iran September 19, 2022. WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS