Regional stability is in the interest of both Saudi Arabia and Iran

The political disputes and religious differences between Saudi Arabia and Iran tend to be magnified rather than an acknowledgment of the common interests between these regional powers. Exchanges of harsh rhetoric between officials make it easy to consider Saudi Arabia and Iran only as “archenemies” and “geopolitical rivals.” However, the example of Iraq—with which Iran fought a devastating war in the 1980s that cost one million casualties and billions of dollars—shows that, when it comes to mutual geopolitical and economic interests between states, differences—including a history of armed conflict—can be put aside. Today, it is hard to find two countries in the Middle East with stronger political, social, and economic bonds than Iran and Iraq. The Shia religion practiced by the majority in both nations is one contributing factor but a larger cause is a desire by both countries to end the US military presence in Iraq.

A similar argument applies to Saudi Arabia and Iran. Many analysts assert that an ongoing “cold war” between the two countries is motivated by religious differences. They believe that Saudi Arabia and Iran compete for the leadership of the Islamic world. This is hyperbole, as each has support primarily in their respective Sunni and Shia communities. In addition, despite significant differences between Wahhabism and Shi’ism, religious distinctions are of minor importance to the Saudi and Iranian elites compared to political and economic differences and competition for regional influence. The iciness between Riyadh and Tehran has never been because of religious preferences so much as a desire for national autonomy and superiority and prestige in the region.

Contrary to common stereotypes, Riyadh and Tehran actually share a number of common interests. Both seek stable oil prices given the importance of the market to their economies. Approximately 79.4 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves are located in Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the biggest portion—64.5 percent—is in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia and Iran account for 35.5 percent of OPEC’s reserves. The two countries have cooperated several times since OPEC’s birth in 1960 to orchestrate crude oil supply and prices. Controlling prices ensures steady oil revenues for all producing countries and more predictability to economic planners in both Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Riyadh and Tehran do battle for regional influence, a competition that has grown since the 2003 US invasion of Iraq deposed the Sunni government of Saddam Hussein and especially since the 2011 Arab Spring. The former produced an even larger US military footprint in the Middle East, while the latter led Iran to expand its activities more deeply to prop up allied regimes like the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. Riyadh and Tehran also strengthened ties with groups and states loyal to them. This struggle for regional power has been very expensive for both countries and caused wide fluctuations in oil prices. A more stable region with significantly reduced tension and armed conflict is the second area of common interest between Riyadh and Tehran.

A third area of common interest is in dealing with Israel and the Palestinian issue. Despite reports of growing intelligence cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Israel, both Riyadh and Tehran still put weight behind the Palestinian cause and are concerned by Israel’s control of Muslim holy sites and expansion into the West Bank, as well as Israel’s undeclared nuclear weapons capabilities. It is telling that Saudi Arabia has not followed the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain in normalizing ties with the Jewish state. An important question to ask here is whether a Saudi-Israeli alliance would benefit Saudi Arabia and the Middle East more than a Saudi-Iranian détente in terms of reducing tensions, boosting economic prosperity, and reducing the influence of outside powers.

A fourth common interest of Riyadh and Tehran is closer relations with the European Union (EU), which is seen as a less troublesome partner than the US, Russia, or China. Normalized relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran would facilitate closer ties with the EU for both.

Forty-one years after the Iranian revolution and the siege of the grand mosque at Mecca, the importance of exporting revolutionary Islam has faded for both Iran and Saudi Arabia. With the US looking to withdraw troops from the region, Riyadh’s reliance on the US as its major defensive ally is also diminishing.

Iran and Saudi Arabia have been able to put aside their differences in the past. Direct meetings and approaches in the late 1990s and in the 2000s under the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad presidency, as well as more recent mediation by Oman and Pakistan—among others countries—bear witness to this capability.

The Middle East’s security and well-being depends on both Saudi Arabia and Iran. If Riyadh and Tehran focus on their common interests, neighboring countries will quickly follow suit. This will help extinguish most of the flames in and around the region and enable peaceful coexistence with Israel. Improved relations between Riyadh and Tehran would not only bring benefits to the Middle East but to North and East Africa, allowing Muslim countries to focus on the reduction of poverty, religious intolerance, and terrorism and promoting democratic reforms.

The incoming Joe Biden administration can play a major role in encouraging rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran rather than promoting a counterproductive and, so far, ineffective effort to create a regional alliance against Iran.

Mohsen Tavakol is a nonresident senior fellow at Atlantic Council. He is also an international business executive, technology entrepreneur, investor and advisor on sanctions, international trade compliance, and business ethics. Follow him on Twitter: @Mohsen_Tavakol.

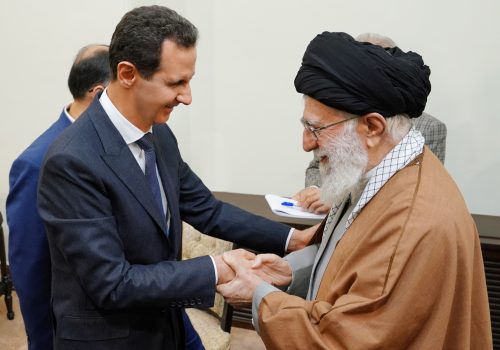

Image: King Salman of Saudi Arabia (front L) is pictured with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (front R) during a family photo session at the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Istanbul Summit in Istanbul, Turkey April 14, 2016. Picture taken April 14, 2016. REUTERS/Onur Coban/Pool