The Abraham Accords plays into Iran’s hands and opens the door for al-Qaeda

After a career gathering secrets for the Central Intelligence Agency across the Middle East and the Muslim world, I reacted to the recent normalization of relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain with trepidation more than celebration. It reminded me of the US-backed agreement signed by Lebanon and Israel in 1983—also in the absence of genuine popular support. That treaty died with the Lebanese government’s February 6, 1984 collapse, which followed unprecedented acts of terrorism against US Marines, French paratroopers, and Palestinian civilians.

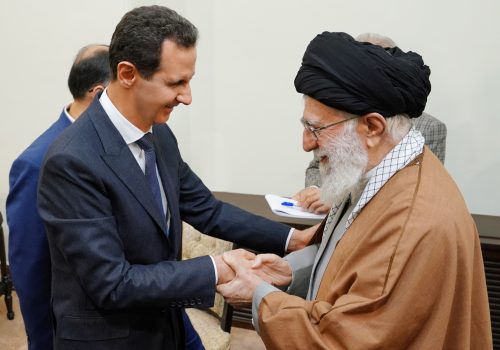

In 1983, the US chose to cut out Syria, which, like Israel, occupied parts of Lebanon, and the local Shia, Sunni, and Druze communities. The Trump administration has also excluded key players in brokering the Abraham Accords. Once again, the US is placing all its eggs in the baskets of autocratic leadership while neglecting the Palestinians and the continued resonance of their cause in the broader Arab and Muslim world.

Whereas President Ronald Reagan’s White House employed exclusion, the Donald Trump White House is relying on coercion. After the Palestinians rejected Trump’s February Middle East peace plan, which aspired to buy their accommodation, his “Plan B” depended on economic and political isolation. But Palestinians are unlikely to accept an imposed peace. In fact, US policy risks uniting Palestinian moderates with more radical elements and pushing their confederation into Iran’s open arms.

In February, the Palestinian Authority cut all ties with the US and Israel, including those relating to security. Then, in September, it resigned from the rotational presidency of the Arab League, with calls across Palestinian communities to leave the league entirely.

Meanwhile, cooperation between Iran and US-designated foreign terrorist organizations Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) has already been on the rise. In February, Iran’s Strategic Council on Foreign Relations predicted “that the Occupied Territories will in the future witness a new Intifada against the Zionist regime that will involve more support from Iran than the previous one.” And, in early September, Hamas and Lebanese Hezbollah held meetings intended to facilitate greater cooperation.

Iran has an additional card to play in leveraging Palestinian radicalization: al-Qaeda.

While some observers still discount extremist Sunni-Shia collaboration, Iran has consistently supported Hamas and the PIJ and, more discreetly, al-Qaeda and the Taliban in certain situations. Relations between al-Qaeda and Iran were strained after the September 11, 2001 attacks and they treat each other with cynicism and mistrust. But, provided some degree of plausible deniability when it comes to common enemies and Iran’s core security interests, al-Qaeda offers Iran an additional and capable proxy for taking the fight directly to Israel and the West.

Al-Qaeda has long leveraged the Palestinian cause in its propaganda. Its leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, responded to Trump’s 2018 decision to move the US Embassy to Jerusalem by condemning Arab states for their “appeasement,” urging Muslims to take up arms and carry out jihad against them and the US. In a 2019 message, Zawahiri referenced US recognition of the Golan Heights as Israeli territory in calling on Palestinians to seek “martyrdom” by attacking Israelis with suicide vests.

Still, al-Qaeda’s record with the Palestinian issue is mixed. Its rhetoric has not been matched with operational focus or success, exposing it to criticism within jihadi circles. But al-Qaeda might indeed be moving in this direction with Iran’s support, whether it wants to or not.

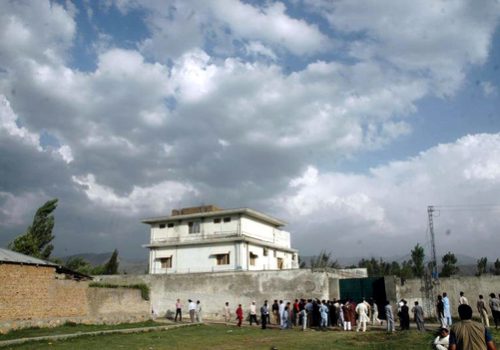

In 2015, Iranian authorities released al-Qaeda’s five most senior operatives from house arrest. Two of Zawahiri’s top lieutenants, Egyptian nationals Saif al Adel and Abu Mohammed al Masri—who were both indicted for the 1998 East Africa bombings—remained in Iran from where they currently appear to support the organization’s worldwide management. The others, including Zawahiri’s Egyptian deputy, Abu Khayr al Masri, and senior Jordanian lieutenants, Khalid al Aruri and Sari Shihab, joined an increasing flow of other formerly Iran-based operatives in Syria. Their mission in first establishing the Khorasan Group and then Hurras al-Din was to plan and execute external operations. But the three Syria-based senior operatives would ultimately perish in drone strikes, along with two other external operations managers, Saudi national Sanafi al-Nasr and Kuwaiti Mohsen al-Fadhli, who had likewise come from Iran.

Fast forward to this past August, when hundreds of fires broke out across southern Israel caused by incendiary balloons launched from the Gaza Strip during an escalation of border tensions. The tactic recalled a spate of late 2016 forest fires that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu suggested were the result of terrorism. Even if Netanyahu’s assessment was partly political theater involving a disagreement concerning fire victims’ eligibility for state compensation, Israel’s tax authority published a list of locations where “it had determined with certainty that these fires were set for nationalist, or terrorist, motives.”

Reflections among jihadi chats also suggested that the 2016 fires were no coincidence, but the work of an al-Qaeda connected network. And coincidence is rare for al-Qaeda, which is well known for adhering to particular goals and plans despite setbacks, as demonstrated by its persistent focus on the World Trade Center even after its failed 1993 effort.

Providing al-Qaeda leaders and their families sanctuary as means to discourage the group from undertaking attacks against Iranian interests does not account for the far greater facilitation and logistical support its operatives receive. It should be anticipated that Iran would expect more for its investment and its risks.

Iran can facilitate al-Qaeda trainers and operatives through its networks and proxies in Syria and Lebanon by partnering them with Palestinians and fellow Sunnis. For al-Qaeda, whose doctrine teaches limited or feigned cooperation when under hostile custodial control, the price would be reasonable and defensible, if required.

One of the many “what ifs” about the US-led war on terrorism is whether Iran could have been incentivized to turn more decisively against al-Qaeda. Just weeks after the US invaded Iraq in 2003, Iran offered a “Grand Bargain”—a proposal sent through the Swiss ambassador in Tehran to settle issues ranging from Iran’s nuclear program to its relationship with terrorist organizations.

In return for its cooperation against al-Qaeda, Iran sought the repatriation of leaders of the Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), a militant Iranian opposition organization then based in Iraq and long listed by the US as a terrorist group for its targeting of American interests. Iran would likely have responded well to a US offer to swap MEK leaders for Iran’s al-Qaeda houseguests. However, White House officials did not reply to the request for dialogue and allowed the MEK in Iraq a negotiated surrender to US forces and protected status. The group was removed from the US State Department’s terrorist list in 2012.

For their part, the Palestinians are hardly blameless in finding themselves losing support from Arab leaders. Perhaps their best chance to secure the two-state solution envisioned under United Nations Resolution 242 came and went with the 1993 Oslo Accords. The two sides came close to agreement at Camp David in July 2000, but then Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat failed despite what many observers considered the most detailed and mutually beneficial negotiations yet.

The ensuing chain of events beginning with the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Arafat’s death in 2004, and the rising political strength of Hamas and the PIJ at the Palestinian Authority’s expense, further pushed the finish line out of reach. Netanyahu’s long tenure, the 2011 Arab Spring, and the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) ultimately realigned priorities among external stakeholders.

While Trump sees the world through a transactional optic, a key lesson is that, even an approach seemingly logical to outsiders, such as peace for land, has failed to overcome the innate fears, insecurities, and grievances felt by the parties at hand. In dismissing prevailing historical realities and passions and endeavoring to pick and choose who gets to decide the outcome, Trump and the Gulf states might have instead fueled a more profound threat that extends Iran’s “axis of resistance” directly into their own houses, including a worrisome al-Qaeda component.

Douglas London retired from the CIA in 2019 after thirty-four years in the Clandestine Service spent largely across the Middle East including several assignments as a Chief of Station. He is currently an associate adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and a non-resident fellow with the Middle East Institute.

Image: Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, US President Donald Trump, Bahrain?s Foreign Minister Abdullatif Al Zayani and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed wave and gesture from the White House balcony after a signing ceremony for the Abraham Accords, normalizing relations between Israel and some of its Middle East neighbors, in a strategic realignment of Middle Eastern countries against Iran, on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington, U.S., September 15, 2020. REUTERS/Tom Brenner