The Hamid Noury conviction in Stockholm—a win for People’s Tribunals?

On July 14, the Stockholm District Court convicted Iranian ex-official, Hamid Noury, to life imprisonment for participating in the mass execution of political prisoners in Iran during the summer of 1988. The verdict is a watershed moment for Iranian society and the international community dedicated to fighting impunity for atrocity crimes, and the first time that a domestic court relied on evidence presented before an International People’s Tribunal.

The judgment, a four hundred-page strong document, reiterates that Sweden has jurisdiction through the principle of universal jurisdiction. This means that the Swedish Criminal Code applies to acts amounting to war crimes independent of where the crimes have been committed, what the nationality of the perpetrators or victims are, and whether the acts are legal in the jurisdiction where they were committed. It is the first time anyone has been brought to justice for the 1988 mass executions in Iran.

Under international law, international crimes have no statute of limitation. In the summer of 1988, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa or religious edict in which he established committees—known as “death commissions”—that sentenced the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI or MEK) fighters and low-level supporters to death. They were considered to engage in mohareb (waging war on God) following their attack on the then young Islamic Republic immediately after the conclusion of the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War.

Commissions were established in all prisons in Iran to investigate whether the political prisoners were still steadfast in their beliefs or prepared to “repent their past sins.” Those who did not repent were to be condemned to death. While the death commission first dealt with MEK fighters, their focus shifted to communist and other opposition groups towards the summer of 1988, effectively liquidating thousands in just three months during July-September 1988.

As Amnesty International reports, most of the prisoners were still serving their terms (however, some scheduled for release and some having served their terms were still in detention pending the provision of guarantees required for their release). Those condemned to death by the committee were hanged within minutes inside the prison and their bodies were buried in unmarked mass graves in the same night. The entire massacre was kept as a state secret and denied by Iranian officials.

The mass execution of political prisoners represents a dark chapter in Iranian history, leaving many Iranian families bereaved. However, for survivors and the families of those killed, the ordeal did not stop there. The families were persecuted by the Islamic Republic and faced subsidiary punishment that can still be felt: survivors were barred from holding government positions; children of the victims were not admitted to schools; families were stopped from holding memorial services; gravestones of victims were destroyed; and gatherings at graveyards were brutally dispersed.

None of those responsible for the mass executions has ever stood trial in Iran. Furthermore, the United Nations failed to record the crimes formally at any court or tribunal. It was against this wall of impunity that survivors and families of the victims established The Campaign for the Iran Tribunal (“Karzar”), which set up an International Legal Steering Committee that eventually created The Iran Tribunal, an International Peoples Tribunal, in 2012. The Steering Committee divided the process into two stages: A Truth Commission, dedicated to hearing evidence on the massacre of political prisoners, and, subsequently, the Tribunal process to assess Iran’s responsibility for the crimes committed.

More importantly, People’s Tribunals do not represent any state power, nor can they compel the perpetrators for crimes against the people of Iran to stand accused before them. However, rather than letting these apparent limitations restrict the powers of the Iran Tribunal, The Truth Commission report highlighted “that these apparent limitations are, in fact, virtues. [The Tribunal is] free to conduct a solemn and historic investigation, unrestricted by the confines of any state or other such obligations.”

Consequentially, the Commission produced a report based on the evidence of seventy-five witnesses heard before the Iran Tribunal. It is in this report that Noury is identified by a witness as an assistant prosecutor and member of the death commission at Gohardasht Prison near the capital, Tehran. Additionally, several Iran Tribunal witnesses testified about the executions at the prison.

One witness recalls “how his friends were taken to the noose without any cause” and how, suddenly, an internal committee called the “death commission” started to execute prisoners. Family members were frequently summoned to the prison to collect the clothes of loved ones or were informed about the execution of a family member while being detained to cause maximum psychological suffering. While the Commission did not report a specific number of prisoners killed at the facility during the summer of 1988, it gave important indications about the scale of the killings, stating that so many were killed at Gohardasht that it was possible to fit all the survivors from six wards into a single ward.

The judgment issued by the Stockholm District Court relied on the Truth Commission report in proving that mass executions had taken place during the indictment period at Gohardasht Prison. Differentiating between the first wave of executions targeting MEK fighters and the second wave of executions targeting leftist and other opposition groups, the court specifically highlighted the role of the Truth Commission report in establishing that the second wave of executions had taken place. Furthermore, during the trial, the Stockholm District Court called forth several fact and expert witnesses that had testified ten years prior at the Iran Tribunal in The Hague.

The court continued to rely on evidence provided by a People’s Tribunal following the Swedish prosecutor referencing the Truth Commission report, as well as the judgment of the Iran Tribunal in the indictment against Noury (see references 9 and 10). In doing so, the Stockholm District Court set a historic precedent in acting upon the findings of the Truth Commission, thus, overcoming the main limitation of People’s Tribunals—namely, enforcement.

It may be hoped that more states and also international organizations and businesses find the courage in joining Sweden to end impunity for international crimes. There should be hundreds of “Noury trials” around the globe sending a strong message that the fight against impunity is not a long-lost battle. The former Iranian official’s conviction sends a powerful message: although the mills of justice may grind slowly, nobody can remain beyond the reach of justice forever.

Marilena Stegbauer is an independent human rights consultant based in London. She is Assistant to Counsel at Iran’s Atrocities Tribunal (“Aban Tribunal”) investigating the bloody November protests of 2019.

Further reading

Thu, Aug 4, 2022

My brother was executed during the 1988 massacre. The Hamid Noury trial verdict is a victory for truth and justice.

IranSource By

Only the truth can heal Iran and the Iranian people’s collective pain and protect future generations from the danger of such crimes.

Wed, Jan 13, 2021

Swedish trial paves the way for accountability for Iran’s human rights violations

IranSource By

Universal jurisdiction proceedings may help prevent another forty-one years of total impunity for perpetrators of grave human rights violations in Iran while granting redress for those affected by the violations.

Wed, Jan 26, 2022

Aban will not die: How truth remains a powerful weapon against the Islamic Republic

IranSource By

In November 2021, The Iran Atrocities (Aban) Tribunal in London investigated if Iranian government officials, police, and military forces had committed crimes against humanity during the November 2019 protests. In front of the eyes of the Iranian public, bit by bit, pieces of the truth were put together.

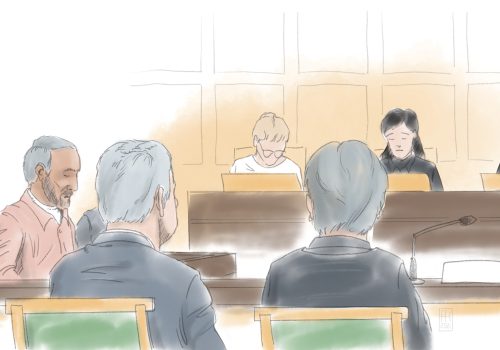

Image: Hamid Noury, who is accused of involvement in the massacre of political prisoners in Iran in 1988, sits with attorney Thomas Soderqvist, during his trial, in this courtroom sketch, in Stockholm District Court, Sweden November 23, 2021. Anders Humlebo/TT News Agency via REUTERS