To help protect Iranian protesters, the State Department should dox security forces

There is a familiar impotence about America’s reaction to the protests in Iran. The online video mélange of masked men, street violence, and bravely bareheaded women have galvanized social media support abroad using #MahsaAmini while highlighting the lack of tangible action from the West. Neither statements of concern from the United States nor TikTok videos have stopped Iranian security forces from violently subduing civil disobedience, just like in past protests, such as the ones in November 2019, when security forces reportedly killed 1,500 and arrested thousands.

Fortunately, Iranians themselves have provided the answer.

The most important things protestors need are safety and the space to protest. That means changing the behavior of individual regime enforcers cracking heads on the street. Here, unfortunately, America’s options are limited. This is actually a broader challenge for the US’s Iran policy both inside and outside Iran. Though it has excellent strategic-level tools—like oil sanctions that can sap the regime’s hard currency—its ability to influence tactical Iranian behavior on the ground with non-lethal means is virtually nil. Of course, it also has military tools that are tactical by definition, but the political risk associated with these generally impedes their use, even in cases where the US is being targeted directly, such as in Iraq, Syria, or the Persian Gulf.

Digging further into the use of sanctions, it’s worth noting that the vast majority of them are US Treasury Department actions aimed at organizations and the Islamic Republic’s leadership. These promise to freeze the institutional finances of institutions like Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison—a moot measure, since the Iranian government does not hold accounts in the US—or those of senior Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC leadership), who are probably undeterrable.

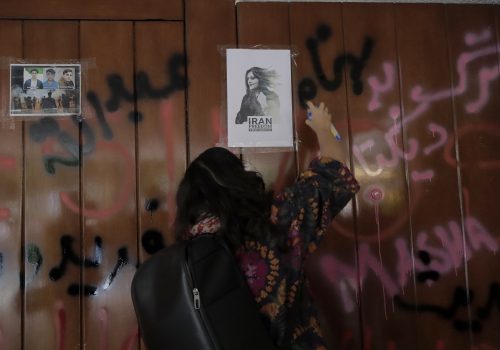

Rather than replicate these often performative measures (as the European Union has done), the US should target the bottom level of Iran’s security establishment, the average militiaman—plainclothes agents and Law Enforcement Forces (LEF)—who have been given orders to crack down since the killing of twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Amini on September 16. Changing the behavior of street-level officers requires tools with a broader applicability than Treasury sanctions and a lower legal standard than even Global Magnitsky sanctions. It needs to be a weapon the US can replicate quickly, easily, and repeatedly.

This is available from Iranians themselves. The regime’s crackdown has produced a significant amount of street-level video footage taken by citizen journalists with smart phones of security forces committing violence against protestors. The US should dox them. The US Department of State has a huge messaging platform via its Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts, such as @USAdarfarsi. It should amplify these videos and crowdsource the identification of the officers involved, some of which Iranians on social media are already doing. Ask followers of these accounts for names of these militiamen committing violence and find out where they live. Like in the United States, policemen and other members of the security forces will be far less willing to act with impunity if they knew they would be instantly famous.

Doxing officers committing human rights abuses would serve as a gray-area action—one still with practical repercussions that falls short of a Treasury action by the US government. Names could be collected at a central registry by the US Department of State and moved up into a formal sanctions process through the Treasury if they kept reappearing. There would certainly be bad information included among the good, but multiple iterations would help remove the bad apples—that is how crowdsourced applications like Waze function.

The next step up from doxing would be feeding those repeat names into an in-between sanction that relies on a lower standard of evidence and is more broadly applicable to individuals. The IRGC Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) designation is unique in this regard. Under the FTO, all people affiliated with or supporting the IRGC—top to bottom—are sanctioned by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) individually. That is, their names and those of their enablers are personally entered into CBP databases. The US government does not have to build out extensive legal cases against them: they will simply be turned away by virtue of their affiliation when they show up at visa windows or ports of entry.

The legal effort required is virtually nil. And this is a real sanction—witness, for example, the Iranian doctor with links to the Basij that was denied entry in 2017. Or Morteza Talaei, an ex-IRGC officer who was heading the Tehran police when Canadian journalist Zahra Kazemi was arrested, tortured, and killed. Talaei was spotted working out in a Toronto gym earlier this year. As these two stories demonstrate, people who support the IRGC and its affiliated bodies do not also forever commit themselves to isolation in Iran. They visit the West—or at least would like to retain the option.

While the senior leadership of the IRGC might not ever be visitors to the United States, the same is not true for their minions, particularly the Basij who are an internal paramilitary subsidiary of the IRGC. And it is definitely not true for all of those retailers, restaurants, and landlords who service them. Their names should all be candidates for CBP’s database.

Both measures rely on Internet access to connect the outside world to all parts of Iran for Iran’s fifty-six million Internet users. Iran slows and cuts Internet access during the peaks of civil unrest to prevent activists and crowds from organizing. Circumventing this Internet censorship must be a key US goal. Part of that is on the West: technology companies like Apple and Google must be engaged to ensure that Virtual Private Network facilitation and other tools are accessible and included in app stores. That doesn’t necessarily help rural Iranians, however, who are the most important part of these—or any—protests. They need to be included in this crowdsourced information loop.

The most promising element of the December 2017-January 2018 unrest was that the demonstrators came from the lower-middle and lower classes, which are precisely the base for the internal security forces like the Basij. These protests are also heavily represented in rural areas, and priority should be given to help those Iranians access the media. For these audiences, adding mediums like radio can help reach them, even if cell phones are also widely used. The names and doxing going into American online channels need to be fed into radio outlets like Radio Farda. Allowing those Iranians to understand abuses for themselves and identify culprits is of the utmost importance in sapping the security forces’ support systems and will to participate.

Anonymity breeds atrocity—in Iran the same as at home. If individual officers of the security forces cannot stay anonymous, they will be more cautious with their actions and may, perhaps, think twice about taking more orders from a regime that has nothing more to give.

Dr. Andrew L. Peek was the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Iran and Iraq from 2017-2019 at the US Department of State.

Further reading

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

The protests in Iran have an anthem. It’s a love letter to Iran.

IranSource By

Shervin Hajipour's “For the sake of” has captivated the whole nation.

Image: FILE PHOTO: Iran's riot police forces stand in a street in Tehran, Iran October 3, 2022. WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS