Defusing Saudi Arabia-UAE tensions through economic rebalancing

The recent disagreement between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) over oil production quotas has drawn attention to broader issues, such as diverging interests in the Yemen war and disputes over borders. Missing from the public discourse, however, is an assessment of the economic factors that are a game changer in Riyadh-Abu Dhabi relations. These conflicting national interests arise from a symbiotic relationship that has created massive economic imbalances that heavily favor the UAE, which Saudi Arabia is taking steps to remedy. Although Saudi Arabia lifted travel restrictions to the UAE for citizens this month in conjunction with the Dubai Expo 2020, much remains unresolved.

The emerging schism is not inevitable. By identifying the economic imbalances contributing to the breakdown, recalibration is possible to rebuild a more balanced relationship that circumvents the zero-sum game that has given rise to the Riyadh-Abu Dhabi dispute. Otherwise, a slew of joint ventures, bank loans, investments, and transport will be disrupted, entailing costly disentanglement. In July, media reports indicated major land travel disruptions at the UAE-Saudi borders, and scores of businesses around the world were impacted. Should the rift continue, major shifts in logistics, as well as shipping and transit routes, will occur.

Economic imbalances between Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Though Saudi Arabia and the UAE are relative newcomers to wealth, as both have built their economies on oil and expatriate labor, each has pursued divergent paths in developing its economy. This divergence is driven by their relative size but also by contrasting economic visions. Saudi Arabia’s gross domestic product (GDP)—which is heavily dependent on oil—was $700 billion in 2020 and its population is thirty-four million, of which an estimated 12.4 million are expatriates. By comparison, the UAE’s GDP—which is less dependent on oil—is $354 billion and its population is nine million, of which about eight million are expatriates.

The two countries have large economic imbalances, including a $17.15 billion annual trade deficit. It is worth noting that the UAE exports $24 billion to Saudi Arabia (6.8 percent of the UAE’s GDP) but imports $6.85 billion (under 1 percent of Saudi Arabia’s GDP). Capital flows are equally lopsided. Saudi tourists—nearly 9 percent of UAE tourists to Dubai—spend an estimated $2 billion annually, while Saudi investors pour an estimated $2 billion into Dubai’s real estate.

Additionally, Saudi trade and capital inflows of over $21 billion comprise 7.9 percent of the UAE’s economy or nearly 13 percent of its non-oil GDP. A disruption in these flows will have a material impact on the UAE’s economy and business model, while the impact on the Saudi economy is insignificant. These imbalances give Saudi Arabia substantial leverage in dictating the terms of a reset in the status quo.

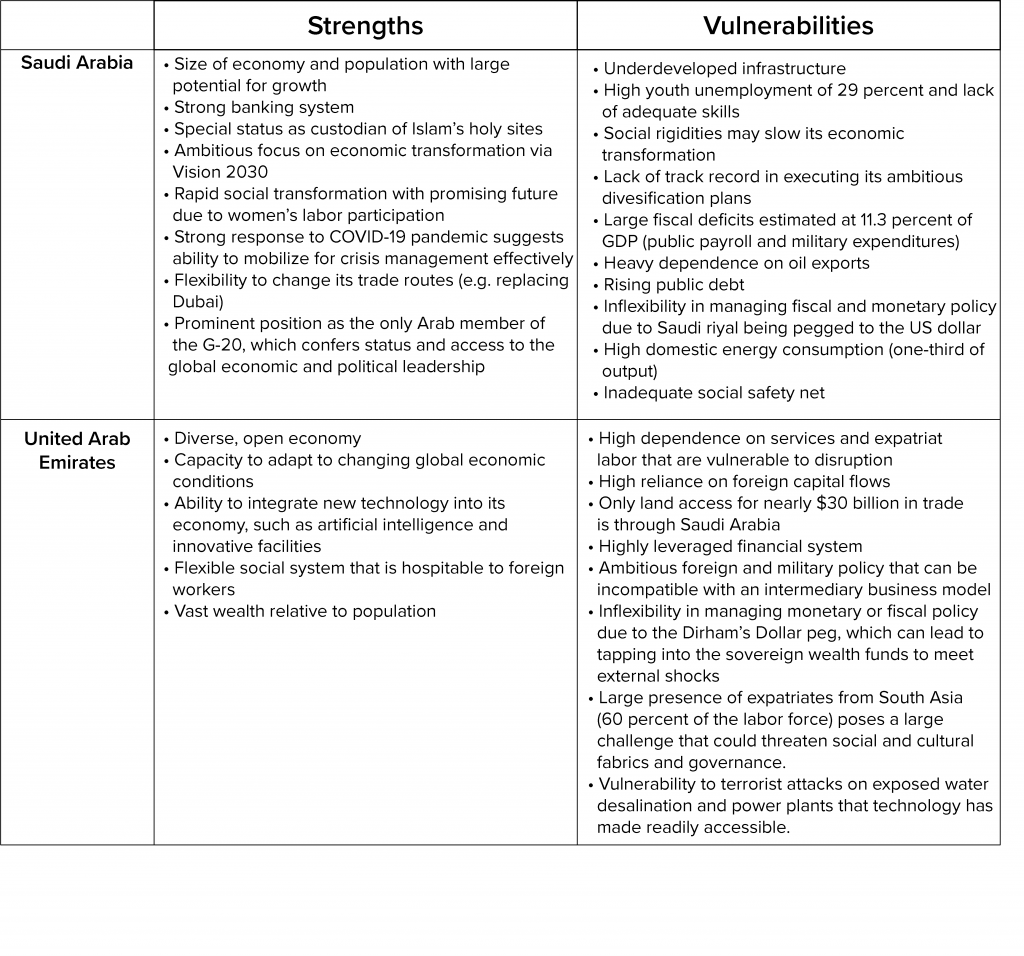

The salient forces that drive these respective economies’ strengths and vulnerabilities—as outlined in the table below—can serve as a guide for any reset in bilateral relations.

Steps to ease tensions

Easing tensions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE is necessary because both countries possess the economic heft and political clout to inflict damage beyond their borders. Thankfully, solutions are feasible because of the strong bond they share that transcends their economic differences. These bonds include a common language, religion, tribal traditions, extensive familial ties, partnership with the United States, and common vulnerabilities to threats from terrorism, Iran, and climate change, among other things. Most importantly, they share the same system of governance as hereditary monarchies and a desire to preserve it. Collectively, these factors offer a conducive framework for resolving their differences.

The comparative analysis in the table above could serve as the starting point for a reset in bilateral relations, possibly within a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) platform. Europe offers a good model of how a culturally diverse group of states with a history of centuries of conflict and fewer common bonds can coalesce as a community underpinned by economic harmony.

There are several paths to defuse the conflict, but they should be built around four core premises. First, though economic disparities are an essential component of the disagreement, a resolution is best achieved in the context of broader political and foreign policy issues. Removing unrelated irritants can create sufficient goodwill to allow for compromises that would be more difficult otherwise.

Second, changes in the geopolitical and economic landscape, as well as technological disruptions, have exposed deep fault lines that necessitate a reassessment on both sides. Such a reassessment entails the viability of their respective economic models. For the UAE, this includes adjusting to new realities where its intermediary commercial role is less pronounced. While oil is a relatively small share of the UAE’s economy, it is an important component of its fiscal budget that entails a larger reallocation of funds from Abu Dhabi to the other emirates.

This is important for the internal cohesion within the UAE, which economic exigencies and opportunistic external meddling can threaten. For Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, oil remains the cornerstone of its economy for the foreseeable future. In return for changing Saudi initiatives on trade and coerced relocation of international companies whose impact falls disproportionately harder on Dubai, the UAE could commit to substantial multi-year capital investments in Saudi infrastructure as a way to rebalance capital flows. Additionally, the reset must rest on developing strategies to offset the economic imbalances that have led to the rupture in relations between the two countries, but should aim to balance gains and losses.

Finally, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have mutual foreign policy concerns. One example of low-hanging fruit that could engender goodwill would be a UAE recalibration of its actions in Yemen, where Saudi Arabia has a disproportionate strategic interest. Other foreign policy issues of joint concern include three related aspects of the important relationship with the US. This includes the security implications of US preoccupation with China as a foreign policy priority and the perceived downgrading of the region in US priorities; the economic implications of balancing US interests against their own in decisions about technology and trade with China; and, finally, the impact of a shifting US attitude towards Iran and its regional implications.

This dispute should not be dismissed as a tempest in a teapot. Should the rupture continue, it could descend into a competitive contest that leads to the disintegration of the GCC, impacting trade, investment, and regional cooperation. Moreover, the recent record heatwaves and forest fires in the US and abroad, the devastating floods in Europe and China, and US plans to increase the production of electric cars will accelerate the inevitable transition from hydrocarbons. As with other technological disruptions, the tipping point can arrive sooner than expected. Regional cooperation on developing and implementing strategies to mitigate the impact of such an eventuality should form the basis for dialogue.

While political considerations are central in defining Saudi-UAE relations, ignoring economic forces may produce temporary solutions that prove unsustainable. In past Arab disputes, the leaders have ultimately recognized that a nation’s most important relationships are with its immediate neighbors, especially those with common borders, culture, language, and religion. This time should be no different.

Dr. Hani Findakly, an investment banker, is the former vice chairman of the Clinton Group, Inc., and the former director of investments of the World Bank Group.

Image: UAE Finance Minister and Deputy Ruler of Dubai Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum (R) speaks to Saudi Arabia's Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Assaf ahead of a group meeting of Gulf and Arab Finance Ministers in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, September 7, 2011. REUTERS/Jumana El Heloueh/File Photo