Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 aims to empower the non-profit sector. Here are three areas to focus on.

With its Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia encouraged businesses to participate in its development and to address national challenges—especially in critical sectors, such as health care, education, housing, and cultural and social programs—rather than focusing solely on generating profits. Vision 2030 calls for a more effective third sector for non-profits, among other things.

Social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is an evolving phenomenon. In June, the Council of Ministers approved the establishment of the National Center for the Development of the Non-Profit Sector (NCNP), which will regulate the sector. The center is one of the National Transformation Program initiatives in Vision 2030, and its purpose is to empower the non-profit sector to achieve a deeper social and economic impact.

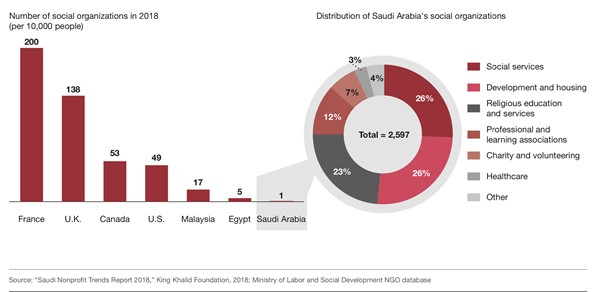

According to academics Sophie Bacq and Frank Janssen, social entrepreneurship is the process of identifying, evaluating, and exploiting opportunities for social value creation through commercial, market-based activities or other resources. Social entrepreneurship has existed in Saudi Arabia for many decades. An early example was a school in Mecca that would cost the equivalent of less than a dollar today. Saudi Arabia currently shows low levels of social entrepreneurial activity compared to other countries, but this may be due to the lack of data on social enterprises in the country. Currently, there is an estimated one not-for-profit social organization per ten thousand people in Saudi Arabia compared to around fifty per ten thousand in Canada and the United States.

According to experts I’ve spoken to, the number of social enterprises in the country has increased in the past decade. This increase is partly due to the work of international foundations (e.g. Ashoka and Acumen), local foundations (e.g. King Khalid Foundation), corporations (e.g. Abdul Latif Jameel Group), some higher education institutions (e.g. Effat University and Dar Al-Hekma), charity foundations, such as for housing and women’s empowerment, and personal initiatives of Saudi entrepreneurs. The community shares a commitment to achieving positive social impact using innovative and financially sustainable methods.

One of the most prominent examples of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is Glowork, a social enterprise that encourages women’s participation and integration into the Saudi workforce. It was founded by Khalid Alkhudair, who started the online Glowork platform in 2011. By 2017, it had placed 27,000 women in Saudi Arabia’s workplaces and found work-from-home employment for over five hundred women living in rural areas.

Social entrepreneurs engage problem-solving skills and local knowledge in search of innovative solutions. Innovation is the building block of entrepreneurship, opening new avenues to create wealth. Social innovation focuses on the addition of social value as part of the mission. For Saudi Arabia to create an enabling environment for social entrepreneurship and unlock social innovation and impact investing, it may wish to address three main issues: government regulation and policy, societal perceptions, and the education system.

Government regulations and financing

The formal institutional environment is essential when it comes to innovation. A challenge Saudi social enterprises face is which type of registration and profit model to adopt. Founders have had to choose between for-profit and non-profit options—there is no middle ground. As a result, some social entrepreneurs incorporate without fully understanding the consequences of the regulatory environment associated with their company’s registration type. Sometimes social entrepreneurs incorporate with a certain model only to find out about new business models that could better serve their interests. However, this issue should be resolved over time with June’s establishment of the NCNP.

Financing is another difficulty social entrepreneurs face. It is vital for social entrepreneurs to find access to capital market funding, given their social mission. This is not an issue specific to Saudi Arabia; it is a global one for most social entrepreneurs. It is difficult to measure social impact or key performance indicators that apply to all types of social enterprises, especially when the legal structure and regulations have not yet been developed for that country’s sector. In addition, the social impact achieved by a social enterprise may not be directly observable and, as a result, could be hard to measure and prove to potential investors and sponsors.

Therefore, the Saudi government may wish to concentrate on devising specific regulations for social enterprises while also offering fees and tariff exemptions and opportunities to bid on government contracts. The government can also support the establishment of social entrepreneurship incubators and accelerators. Existing incubators and accelerators have contributed much to the entrepreneurship ecosystem in Saudi Arabia, but not many exist for social entrepreneurship currently.

Saudi society’s perception of social entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial activity can be facilitated or hindered by certain socio-cultural practices, values, and norms. Indeed, a social entrepreneur’s motivation is partly influenced by societal perception about the desirability of pursuing entrepreneurial ventures.

A society must value creativity and the implementation of new ideas to flourish economically and culturally. Therefore, increasing society’sawareness of social entrepreneurship should be one of the most urgent priorities for the newly established NCNP. Currently, Saudi society may not clearly understand the differences between standard work, charity work, social entrepreneurship, and social responsibility. However, improving the perception of social entrepreneurship is more difficult than simply creating an appropriate regulatory environment. Involving the media to feature profiles of domestic heroes as well as giving formal recognition to social entrepreneurs will go a long way to improving societal perceptions about social entrepreneurship.

The twelve Saudi social entrepreneurs I interviewed for my research over the course of four years had expectations built from their education, including examples of successful foreign social entrepreneurship case studies. At the beginning of their endeavor, they also believed that Saudi Arabia’s normative environment provided favorable conditions for social entrepreneurship. In my research, I found that they later realized the gaps in the environment, yet still managed to adapt to some of the issues they faced in the field.

Despite operating in a non-institutionalized context, the social entrepreneurs I studied were optimistic, confident, resilient, and hopeful—all of which are important traits for leaders and visionaries trying to make a change and solve social issues. If these strengths are combined with the right regulations and societal support from the beginning, social entrepreneurs could thrive even more and increase their chances of success. Moreover, if social entrepreneurs start their endeavor with more awareness of the institutional environment, they may be better equipped to deal with the challenges they face.

Social entrepreneurship in the Saudi education system

Education can prepare social entrepreneurs to identify barriers and devise strategies to overcome them. Currently, social entrepreneurship is being integrated into the curriculum of some Saudi universities, with major events and workshops taking place to promote the concept, such as in Dar Al-Hekma University and Effat University. However, Saudi social entrepreneurs still often have turn to educational resources from abroad to learn more about the concept of social entrepreneurship. This reliance on foreign material can be problematic because it does not consider the differences in the local context, like cultural norms and the different ministries’ evolving regulations.

It is important to foster formal and informal learning about social entrepreneurship by offering modules in Saudi universities and schools, as well as courses and webinars and Arabic material on social entrepreneurship. Educational institutions can host workshops and competitions, provide technical support to social entrepreneurs, and connect social entrepreneurs to a larger audience, including public, private, and international organizations. Educating citizens about social change and social entrepreneurship will help them generate ideas to tackle urgent social issues and provide them with positive role models.

Conclusion

Social entrepreneurship is an evolving phenomenon and by far the most crucial type of entrepreneurship in allowing citizens to play an active role alongside the government in solving environmental and social issues in Saudi Arabia. The government has taken an initial positive step to create a supportive regulatory environment by establishing the NCNP. The next step would be to increase positive societal perceptions about social entrepreneurship, provide educational opportunities to students and would-be entrepreneurs, and highlight case studies and role models operating in the Saudi context. The goals of Saudi’s Vision 2030 will require innovation on all fronts, and social entrepreneurship can be a leading driver of the country’s advancement once nurtured properly.

Dr. Ghadah W. Alharthi is an associate director and lecturer at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. She is also a Middle east specialist and cultural consultant at Barker Langham. Follow her on Twitter: @GhadahWA.

Image: A large banner shows Saudi Vision for 2030 as a soldier stands guard before the arrival of Saudi King Salman at the inauguration of several energy projects in Ras Al Khair, Saudi Arabia, November 29, 2016. REUTERS/Zuhair Al-Traifi