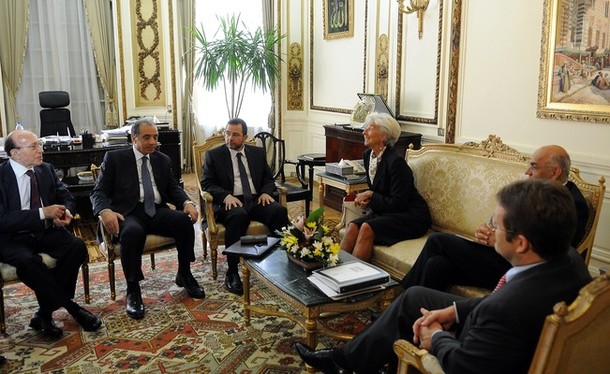

The Arabic press reported on August 22, 2012, that Finance Minister Momtaz al-Saeed denied rumors of an imminent devaluation of the Egyptian pound following his meeting with Managing Director Christine Lagarde of the IMF who is currently visiting Cairo along with an IMF mission. He stated that devaluation was not a condition for the $4.8 billion loan that Egypt was requesting from the IMF.

On one level, denying that devaluation is coming soon is standard practice for ministers of finance and governors of central banks. Simply admitting that the currency was going to depreciate would turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy as everyone rushed to convert domestic money into foreign currencies, thereby creating a run and forcing devaluation as the country started to run out of foreign exchange reserves to defend the currency. No minister or governor wants to be put into that position and Momtaz al-Saeed’s denial can be considered par for the course.

But is there a case for devaluation, and if so, should the IMF make it a condition in the program being negotiated? There has been, and remains, a strong preference in Egypt for keeping the Egyptian pound stable. While the exchange rate system is formally defined as “managed floating,” one could say that it is more managed than floating. Take the period from the fall of Hosni Mubarak in February 2011 to now. The cost of keeping the currency stable resulted in a loss of international reserves of over $20 billion. Over the same period, the Egyptian pound depreciated by only 3.5 percent with respect to the US dollar. Clearly, the Egyptian authorities valued relative exchange rate stability over the 60 percent loss in foreign exchange reserves.

Two simple indicators point to an overvalued Egyptian pound. First, inflation in Egypt has been running close to 10 percent a year in 2010-11, while it has averaged only 2 percent a year in its principal trading partners. Egypt is thus steadily losing external competitiveness. Second, the markets (both in Egypt and abroad) are already pricing in a devaluation of the pound as reflected in the levels of interest rates on government bonds. The government is now paying over 15 percent on its 6-9 months paper, while foreign interest rates are in the 1-2 percent range for government bonds of comparable maturities. Based on both these indicators one could argue that a devaluation of around 8-10 percent is about right.

While understanding the Egyptian position that a sharp devaluation would be disruptive and create a jump in inflation, it is hard to see how the IMF can avoid making the exchange rate more flexible, which will naturally mean an initial devaluation, a condition for the program. Certainly, there is no economic case for keeping the rate unchanged. What is there to prevent any external financing being provided, including from the IMF, going right back out? If Egypt wants to achieve external competitiveness without changing the external value of its currency, it only has to look to the Eurozone to see what the costs are of this type of misconceived policy. There is no way the new government in Egypt could buy into the type of austerity policies that would be needed to keep the rate where it is currently.

Mohsin Khan is a senior fellow in the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East focusing on the economic dimensions of transition in the Middle East and North Africa.

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Image: 610x_138.jpg