In a region long defined by proxy wars, sanctions, and sectarian divides, a quiet shift is underway. A new chapter in US-Iran relations is emerging, centered on renewed nuclear talks. But beyond the centrifuges and uranium stockpiles lies a far bigger opportunity: the future of global energy cooperation.

As landmark negotiations unfold between the government in Tehran and the new administration of US President Donald Trump, the prospect of a new US-brokered agreement with Iran could serve as a turning point—not merely another iteration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), but a wider strategy encompassing nuclear compliance, regional de-escalation, and energy collaboration. Such a deal would reframe negotiations from an exclusive focus on uranium enrichment and arms controls to a broader architecture centered on commerce, infrastructure, and regional integration.

If implemented with foresight, transparency, and inclusive governance, establishing a regional gas corridor could transform the Middle East’s fractured geopolitics into a system of mutual benefit.

Mapping a “Gas Peace Corridor”

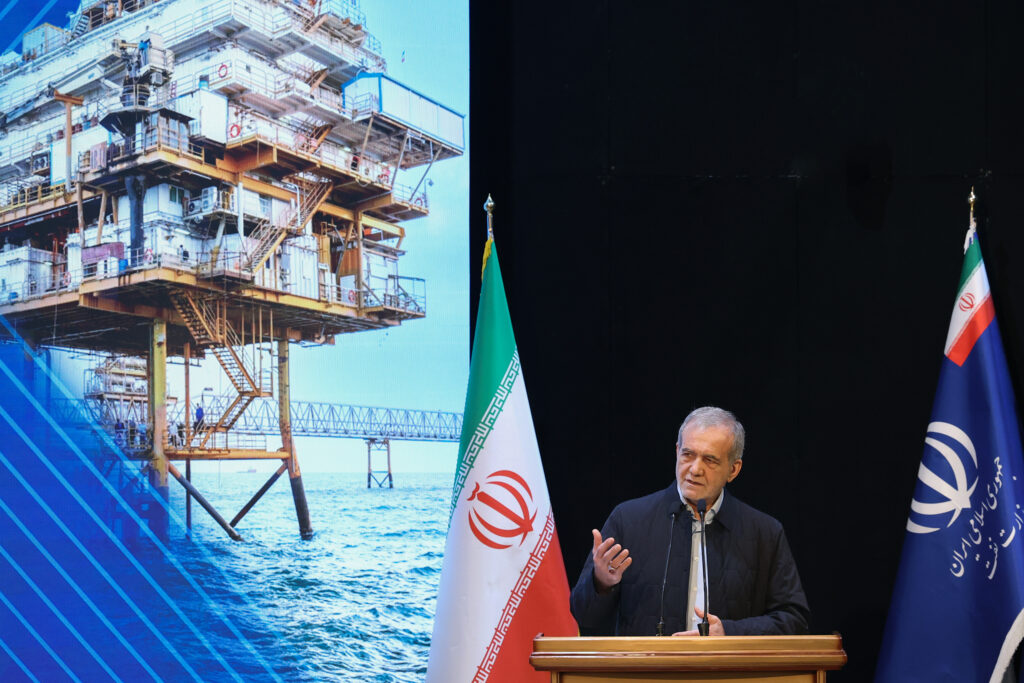

At the center of such opportunity is South Pars, Iran’s share of the world’s largest natural gas field. Straddling the maritime border with Qatar, where it’s known as the North Dome—South Pars, holds an estimated 14 trillion cubic meters of gas and eighteen billion barrels of condensate. That’s more than forty percent of Iran’s proven gas reserves and nearly eight percent of the world’s total.

Despite this immense resource, South Pars remains significantly underutilized due to international sanctions, underinvestment, and outdated infrastructure. Although Tehran launched a seven billion dollar initiative in March 2025 to sustain pressure levels in the aging field, the scale of South Pars demands much more: international partnerships, modern technology, and access to global markets.

This is where diplomacy and energy intersect.

Under this framework, Iran would commit to placing its nuclear energy program under comprehensive International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) monitoring, curbing support for regional proxies, and opening its natural gas sector to foreign investment. In return, Tehran could gain access to up to $120 billion in frozen assets, kickstart its economy, and begin exporting gas at scale to neighboring countries and Europe.

The blueprint envisions a “Gas Peace Corridor,” serving as the primary conduit for this transformation—connecting Iran’s South Pars field through Iraq and Syria to the Mediterranean, with links extending into Turkey and the European grid.

An Iranian pivot from military to markets

Iran, for its part, stands to gain enormously. Home to the second-largest proven gas reserves in the world, second only to Russia, Tehran has long been isolated from the global energy economy. Its domestic sector suffers from inefficiencies, periodic blackouts, and reliance on unsustainable subsidies. Despite sitting atop the world’s second-largest proven gas reserves—33.8 trillion cubic meters—Iran struggles with domestic shortages. In winter 2023–2024, peak demand exceeded 800 million cubic meters per day, while supply hovered around 700 mcm/d, leading to rolling blackouts and industrial shutdowns. A foreign investment–backed development of South Pars would allow Iran to rebalance domestic demand and redirect surplus toward exports, reducing pressure on internal subsidies that cost the government an estimated $63 billion annually.

A strategic pivot away from militarization toward markets would allow Tehran to modernize its energy infrastructure, reenter global trade networks, and redefine its international image. A successful transition from isolation to integration could open Iranian markets to US and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) investment, expand regional trade, and reduce the economic rationale for military adventurism.

This would mirror and modernize the long-dormant Iran–Iraq–Syria pipeline, also known as the Friendship Pipeline, which was initially proposed in 2011 but was derailed by civil war, sanctions, and political resistance. Today, with the region searching for stability and energy markets desperate for alternatives to Russian gas, the geopolitical logic of that project is stronger than ever. A re-imagined peace corridor would also be an economic lifeline to post-conflict states and a bridge between long-divided regional powers.

In economic terms, transit revenues and associated infrastructure investments could inject billions of dollars annually into transit countries like Iraq and Syria, serving as a stabilizing force amid reconstruction efforts.

Global opportunity

This corridor has clear benefits for the West, too.

For Washington, backing such an initiative could reassert US leadership in a region where its influence has waned. If designed, financed, and operated by US and allied firms, the pipeline could generate significant long-term returns through tariffs, service contracts, and equity stakes, embedding American business interests into the region’s energy future.

Once fully operational, the Gas Peace Pipeline could transport up to one billion cubic meters of natural gas (bcm) annually, equivalent to nearly one-fifth of Europe’s current import needs. Such capacity could rival existing corridors like the Nord Stream system and significantly bolster Europe’s energy diversity and resilience.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

At its peak, Russian gas accounted for over 40 percent of the European Union’s imports; even after sanctions and supply disruptions, the continent remains vulnerable to shortages and price fluctuations. By enabling the flow of Middle Eastern gas, particularly from a reserve as vast as South Pars, Europe could stabilize prices, reduce dependency on Russian supply, and align with its climate goals by replacing coal and oil with cleaner-burning gas.

Expanding gas exports from South Pars also aligns with the EU Green Deal and global net-zero ambitions, with the potential to displace an estimated 100–150 million tons of CO₂ emissions annually, particularly by substituting coal in power generation across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Natural gas emits approximately fifty to sixty percent less CO₂ than coal per unit of energy produced.

The war in Ukraine and subsequent energy crisis underscored the fragility of relying on a single dominant supplier. South Pars gas, transported through a modern regional pipeline system, would offer a reliable alternative, especially since Europe’s gas demand is projected to remain significant well into the 2030s. By aligning with this Middle Eastern initiative, the EU could secure long-term supply agreements while promoting cleaner alternatives to coal in countries like Poland and Germany, thereby supporting its own decarbonization strategy.

In March 2024, the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) released its Global Gas Outlook 2050, forecasting a 34 percent rise in global natural gas demand. Meanwhile, Europe, with approximately ninety percent of its consumption sourced from imports, would benefit from a diversified and secure energy supply at a time when energy geopolitics returns to the forefront.

Yet this vision also carries risks. Russia is unlikely to welcome a pipeline that competes for its most critical market. Moscow may respond by deepening ties with Tehran or by fostering instability in key transit zones to derail the project. Conversely, the deal could pressure Russia diplomatically, creating leverage for Washington and its allies in negotiations over Ukraine and broader European security.

A regionally stabilizing force

Turkey, already a key energy transit hub, would gain geopolitical capital as the linchpin between the Middle East and Europe. Hosting a major leg of the gas corridor would increase its negotiating leverage with both Brussels and Washington, particularly on contentious issues like NATO expansion and regional security. It would also deepen Turkey’s economic ties with Iraq and Iran, strengthening its regional position at a time of multipolar competition.

The gas peace pipeline would also serve as a stabilizing force for Syria and Lebanon—both economically and in terms of security—under the joint guarantee of the United States and Iran, whose cooperation would be anchored in their investment agreement. Syrian reconstruction efforts could be jump-started by pipeline development and transit revenues, gradually shifting the country from battleground to bridge. For Iraq, with its central geography and ties to both Tehran and the West, this project could accelerate its emergence as a regional energy corridor.

The GCC would also stand to benefit. Joint ventures in Iranian gas development would allow the GCC to diversify their portfolios, export routes, and hedge against volatility in oil markets. Economically, such cooperation would foster interdependence, while politically, it could cool long-standing rivalries. The political dividends for all stakeholders, including Turkey and Qatar, would be no less significant than the commercial ones. Regionally, the project could foster greater cohesion and economic integration in the Middle East. Internationally, it would offer Europe a viable alternative to Russian gas, reinforcing energy security across the continent.

The broader regional effects would also be notable. Reduced Iranian support for groups like the Houthis could de-escalate the conflict in Yemen, increasing security in the Bab al-Mandab Strait—a vital chokepoint for global shipping. Jordan and Lebanon could gain access to affordable energy, easing economic crises and supporting development goals.

The pathway forward lies not in reviving failed doctrines of containment or conflict, but in embracing a pragmatic doctrine of peace and commerce. Energy, in this vision, is not merely a commodity—it is a diplomatic instrument, a stabilizer, and a platform for cooperation.

Rather than trench lines and warships, the region could be connected by pipelines and trade routes. Rather than exporting instability, it could export energy and opportunity. And rather than cycling through confrontation, regional powers—under the facilitation of the United States, and in alignment with European interests—could craft a new era where shared prosperity becomes the foundation of durable peace.

Energy talks, while unconventional, mirror the kind of transactional diplomacy that characterized the Trump administration’s foreign policy, focused on tangible economic outcomes and energy price relief for American consumers. While the stakes of energy diplomacy are high, so is the potential for a lasting impact—economically, strategically, and diplomatically. The convergence of energy needs, geopolitical shifts, and strategic opportunity makes this not only feasible but urgent. What is required now is leadership—bold, strategic, and clear-eyed enough to see that the path to peace may run through a pipeline.

Luay al-Khatteeb is the former Minister of Electricity in Iraq and a member of Iraq’s Federal Energy Council. He can be found on X @AL_Khatteeb.

Further reading

Thu, Apr 10, 2025

Iran is at an unprecedented crossroads over its nuclear program

MENASource By Alex Plitsas

The Middle East is experiencing a rare re-alignment that puts Iran in an unprecedently vulnerable position.

Thu, Apr 3, 2025

Washington halted the Iraq-Iran electricity waiver. Here is how it’s perceived by Washington and Baghdad.

MENASource By Ahmed Tabaqchali, C. Anthony Pfaff

By making Iranian energy more costly, the United States hopes to incentivize Iraq to diversify its energy sources and reduce its dependency on Iran.

Fri, Apr 11, 2025

The Iran nuclear talks are Trump’s decisive moment on military strikes

MENASource By Daniel B. Shapiro

Within a relatively short time, Donald Trump is likely to face the decision point on whether or not to pursue a military strike against Iran.

Image: March 8, 2025, Tehran, Iran: Iranian President MASOUD PEZESHKIAN speaks during the signing ceremony of the South Pars gas field contract, an energy investment project worth 17 billion dollars, in Tehran. Pezeshkian warned that the country has a water shortage and that problems will arise if resources are not used economically. (Credit Image: © Iranian Presidency via ZUMA Press Wire)