Jordan was never ‘boring.’ A vibrant protest movement has been ignored for too long.

Jordanians were blindsided on April 3 with news of an alleged coup plot involving King Abdullah’s half-brother and former crown prince, Hamzah. A Washington Post story broke the news early evening Amman time as phones across the country began to buzz with WhatsApp notifications questioning what was really behind the headline. With no announcements coming from official Jordanian sources and out of an abundance of caution to avoid putting Jordanian contacts in trouble, I quickly turned to Clubhouse in hopes of understanding what was happening on the ground. Just two weeks earlier, I had also tuned in to listen to Jordanian voices in the aftermath of a COVID-related tragedy that rocked the country and spurred a number of protests and an all too familiar security crackdown.

Over the next several days, Jordanian officials confirmed the arrest of two dozen individuals accused of undermining the country’s stability, and declared that Prince Hamzah had been asked to refrain from what they called activities that targeted Jordan’s security and stability. Although under house arrest, Prince Hamzah’s last recorded messages—where he defended himself and described that he was being silenced for simply connecting with his countrymen and assuring them that there were still members of the Hashemite family “who care for them and who will put them above all else”—were released to the BBC and quickly spread across social media platforms. On April 5, the Royal Court issued a statement with a letter from Prince Hamzah declaring his allegiance to his elder brother King Abdullah, seemingly putting the family discord to rest. On April 7, King Abdullah issued a letter to the Jordanian people, where he described the pain and anger he felt at the “sedition” that came “within and without our house,” while assuring them that he had taken the “necessary measures” to safeguard Jordan’s security and stability.

The view from the ground

By most accounts, what happened in Jordan was not an attempted coup. It was, however, the manifestation of two trends the country’s leadership ought to be more proactive about addressing: the rising corruption and corresponding sense of injustice felt by Jordanians, and the increasingly vocal critiques of the role that said leadership plays in overlooking corruption and silencing calls for reform. So far, the government has not provided evidence that Prince Hamzah engaged in any serious attempt to threaten the crown. The fact that a member of King Abdullah’s own family, a former crown prince, appears to have ruffled feathers for simply listening to Jordanians express their frustration with the direction of the country during visits he made to their homes could not serve as a starker example of the current state of freedoms in the country. The authorities appear to be threatened by any attempt by Jordanians to hold them accountable, whether through protests on the streets, conversations in their own homes, or through public shaming as the prince eventually did in his April 3 video message.

Jordan weathered the 2011 Arab uprisings that rocked the region over the past decade but has seen regular protests, calls for reform, and an overwhelming sense of frustration and hopelessness among Jordanians struggling to make ends meet. In parallel, the Jordanian government—overtly represented by its security and intelligence agencies rather than the monarchy itself—chose to clamp down on such dissent by banning protests, tightening cybercrime laws, and restricting the country’s historically active teachers’ syndicate.

As all eyes turned to the “royal intrigue” in Jordan, some analysts referred to the kingdom using an array of clichéd adjectives from “boring” to “a haven of stability.” Meanwhile, most Jordanians were simply struggling to understand what happened on April 3 and why their protests and calls for reform had suddenly gained international attention.

Jordanians were skeptical of the full-court press that the government engaged in to rally domestic and international support against what it described as attempts to destabilize the country’s security with little evidence to show for it. Until more evidence of the so-called sedition is released, Prince Hamzah’s final recorded statements will continue to ring in Jordanian ears, as he spoke to the heart of the concerns many have about economic hardship, rampant corruption, and what he saw as an overall deterioration in the country’s progress and standing. In the court of public opinion, Prince Hamzah appears to have captured the admiration of many Jordanians. Since the events of April 3, his picture has flooded Jordanian social media avatars, and hashtags in support of him continue to trend in the country.

Covid and a struggling economy

Jordan’s economic woes have only been punctuated by the coronavirus pandemic. The resource-poor country was initially lauded for containing COVID-19 effectively with a complete lockdown that kept cases shockingly low, but the government struggled to manage the economic fallout. While the strict lockdowns helped to “flatten the curve,” unlike Western or neighboring oil-rich Gulf countries, Jordan could not provide enough economic assistance to those who were losing jobs and livelihoods.

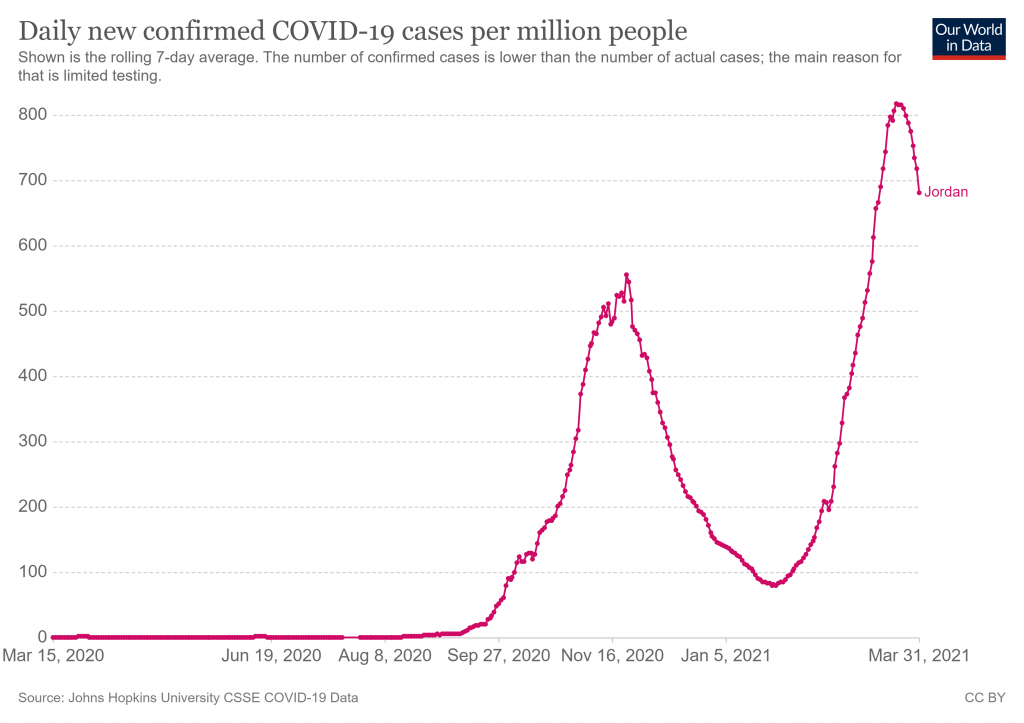

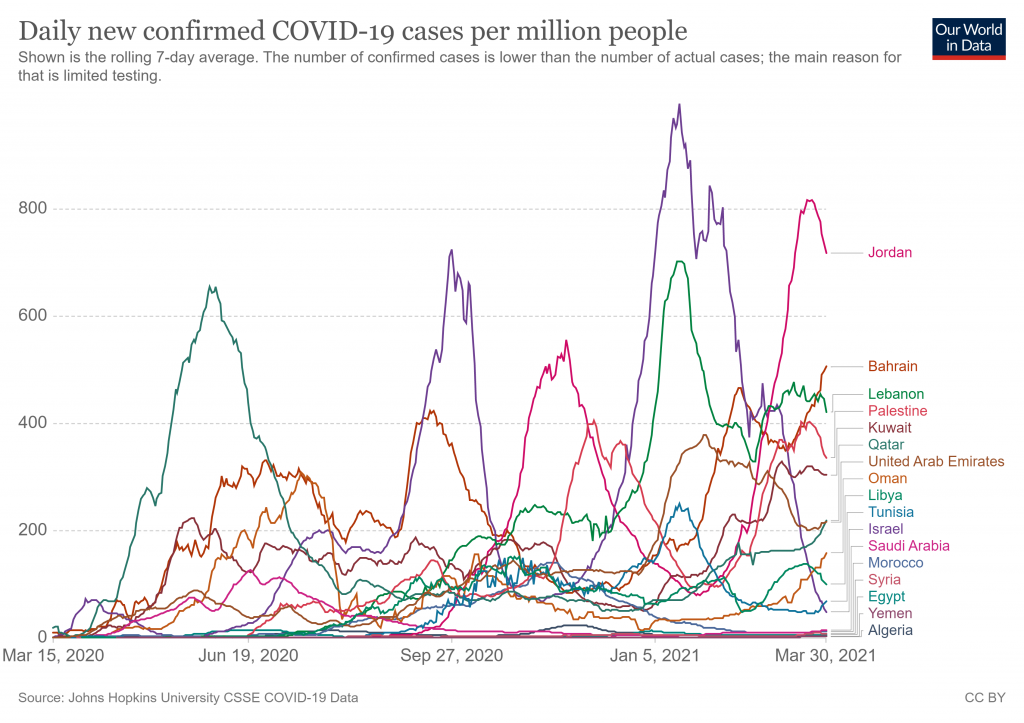

As the pandemic continued to decimate the country’s critical tourism sector, unemployment rose to 25 percent, remittances declined, and as more Jordanians could barely make ends meet, protests ensued in several cities. Jordanians blamed the government for mishandling the outbreak with inconsistently applied restrictions. With the beginning of the new year, Jordan witnessed a brutal second wave of the pandemic, and by the end of March the country had the highest daily number of new confirmed COVID infections (717) and deaths (9) across the Middle East and North Africa.

The near-breaking point came on March 13 at government hospital in Al-Salt, a hillside town near the capital, where oxygen was cut to a COVID recovery ward, causing the death of eight patients. Protests erupted outside the hospital, with angry family and community members chanting anti-government slogans. In a rare appearance, King Abdullah visited the hospital within hours and was visibly upset as he questioned the hospital director about the failures that led to the tragedy. Victim’s families reported having to purchase their own oxygen tanks to keep their relatives alive, while others described how short-staffed the hospital was. For most Jordanians, despite the resignation of the health minister and the king’s impassioned anti-corruption speech on March 15, the tragedy was just another sign of the government’s mismanagement of the pandemic. Incidentally, Prince Hamzah paid a visit on March 14 to offer condolences to the family of one of the hospital victims, and likely listened to their frustrations. The images of him consoling the families were widely shared on social media during a time when Jordanians were seeing the pandemic, and government mismanagement, ravage the country.

A clamp down on protests

Months before the pandemic reached its peak in Jordan, large-scale protests erupted around the country in July 2020, led by Jordan’s public school teachers. The country’s largest and most well-known syndicate representing educators was abruptly—and by most accounts illegally—shut down, its leadership arrested, and its supporters beaten and threatened. Such a harsh crackdown by Jordanian authorities signaled a real fear that what began as protests by teachers about wages was expanding beyond the scope of the issue, amassing popular support among economically frustrated and politically disenfranchised Jordanians. Smaller-scale protests continued in the months after, with Jordanians calling for an end to the emergency law that they saw as a tool to limit criticism of the government.

A muzzled press

As news of the so-called coup attempt broke on April 3, Jordanians had to turn to Western media outlets to find out what was happening in their own country. Local journalists lamented the state of the press in their country, which has witnessed in recent years journalists prevented from covering protests, social media posts criminalized, and gag orders imposed when important news breaks out (such as during the teachers’ strike in the fall of 2019). A leading independent media outlet in the country asked in an op-ed, “Is Journalism Still Possible in Jordan?”

With Prince Hamzah’s story not dying down after the April 5 announcement of the royal family’s reconciliation, Jordanian news outlets were placed under yet another gag order and prevented from reporting on the subject. Jordanians had already turned to social media after the news broke to get the latest updates, share their allegiances and frustrations, and analyze what was happening in their country. While the discussions mostly occurred on Twitter and Facebook, the new audio-only platform Clubhouse was also a popular choice for Jordanians whose typical in-person political discussions in family homes and cafes were limited due to coronavirus restrictions and fear of repercussions.

A shrinking social media space

Although the Clubhouse app was recently blocked in the country, some users circumvented the restriction using Virtual Private Network (VPN) workarounds. As one Clubhouse user decried, “How about [the government] also block Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and bring us back to the Stone Age?” In several rooms that emerged daily on the app, I heard Jordanians inside and outside the country speak relatively openly. Some activists voiced support for a “constitutional monarchy” closer to the British model, while others explicitly accused government figures and royal family members of corruption. Lawyers also chimed in, explaining the gag order’s nuances and the potential cases that could be brought against the individuals arrested in the alleged corruption scheme.

An inconclusive future for reform

Prince Hamzah seems to have touched a sensitive nerve. His appeal to the Jordanian public and ability to listen to their concerns during a difficult time for the country may have worried the king’s advisors. But his words did not initiate or inspire calls for reform in Jordan. They were merely echoing the protests and calls for change that had been taking place over the past several years. As one Clubhouse user noted, “With all due respect, Prince Hamzah did not open any door or start any movement… that existed and has been well documented for years.” But probably the most telling commentary was the disappointment one Jordanian had to King Abdullah’s letter addressing the week’s events: “I expected to hear from the king something along the lines of ‘I hear your concerns, and I will ensure that we undertake a genuine reform effort that will address my countrymen’s pain and suffering.’” The letter stopped short of addressing accusations of corruption by the royal family and the Jordanian government, or even validating Jordanian frustrations that had been boiling over the past several months.

The latest dispute with Prince Hamzah and the broader issues it raised about corruption and reform mean that the Jordanian government (equally represented by the monarch and the institutions he leads) can no longer use the kingdom’s international standing, as both a mediator in regional conflicts and a bulwark of security for the West, as a pass to avoid addressing growing economic and political challenges at home. The greatest risk to Jordan’s stability remains that political and economic reform has been delayed for too long. The little space left for Jordanians to express their legitimate frustration and dissent is narrowing every day.

Tuqa Nusairat is the deputy director of the Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs. Follower her on Twitter: @TuqaNusairat.