Lebanon and Israel: Blue line tensions

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)—now beginning its forty-third year of “interim” service in southern Lebanon—recently intervened to defuse an armed standoff between Israeli and Lebanese soldiers along the “Blue Line:” the line of Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon demarcated by the United Nations in 2000. These confrontations occur periodically. Why?

The short answer centers on uncertainty over where exactly Lebanon ends, and Israel begins. Three lines have been cited through the years. In reverse order, they are the 2000 line of Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon (Blue Line), the 1949 Israel-Lebanon Armistice Demarcation Line (ADL), and the 1923 “international boundary” between Palestine and Lebanon.

When Lebanon and Israel signed an armistice in March 1949, they agreed that the ADL dividing them would correspond exactly to the 1923 international boundary demarcated in 1922 by Anglo-French surveyors. In 2000, when Israel decided to evacuate its forces from Lebanon after some two decades of occupation, the UN landed the job of confirming the withdrawal. The task was of great political sensitivity, because Lebanese Hezbollah was threatening to continue its armed resistance to occupation unless Israel’s withdrawal was one-hundred percent complete.

UN cartographers found, however, that determining where exactly Israel became Lebanon was not simply a matter of referring to the 1923/1949 line. For one thing, the 1923 line had been demarcated by widely spaced stone pillars connected mainly by straight lines. There was no river or dominating terrain clearly depicting a dividing line. And some of the references used by the original surveyors were ambiguous. Indeed, even in the bucolic 1950s when Lebanese and Israelis lived in peace on their respective sides of an unfenced ADL—often returning straying livestock to one another—the UN felt obligated to update the demarcation, and it did so (except in one long-disputed area).

In 2000, UN cartographers tried and failed to find the updated 1950 ADL demarcation. Somehow it had disappeared from the UN headquarters in Jerusalem and the archives in New York. Neither of the parties seemed to own a copy. The absence of this fundamental document led to disputes on the ground, especially along the eastern stretches of the line near the Israeli town of Metula.

One of the disputes, had it been decided in Lebanon’s favor, would have divided an existing Israeli kibbutz (Misgav Am). Lebanon would eventually produce map coordinates that appeared to come from the 1950 demarcation: Coordinates that seemed to buttress its position in some disputed areas. But the UN—eager to produce a line causing the least amount of aggravation in terms of moving civilians—declined to declare the coordinates genuine. It depicted the resulting Blue Line as a “practical line.”

Indeed, Lebanon and Israel were able to accept a line very close to—if not identical with—the 1923/1949 line. Hezbollah raised no objection: The line passed through predominantly Shia areas dominated politically by the organization, and Hezbollah’s leadership cadre wished to avoid subjecting its constituents to further hardship after years of warfare. In 2006 it would change its mind, bringing destruction to much of Lebanon by crossing the Blue Line to kidnap Israeli soldiers.

The Blue Line also extended along the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, seeking to replicate the boundary between Lebanon and Syria. It was there that Hezbollah invented its pretext for perpetuating its status as Lebanon’s “resistance,” claiming that part of the occupied Golan Heights—the so-called “Shebaa Farms”—was really occupied Lebanese territory. This claim—dismissed by the UN—persists to this day.

Yet the relatively uncontested portion of the Blue Line dividing Lebanon from Israel-proper proved problematical as well. For purposes of military defense, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had—during the occupation of southern Lebanon—fenced its version of the 1923/1949 line completely. In some places the 1923/1949 line itself was unsuitable for a defensive position. Sometimes the fence protruded a bit into Lebanon. Sometimes it took advantage of high ground just inside Israel. And sometimes the fence followed the line itself.

When, therefore, the Blue Line was demarcated, IDF defensive positions—labeled “technical fences”—north of it were evacuated. But some remained south of the line, within undisputed Israeli territory. Lebanon, still smarting over a Blue Line it saw as different—to its disadvantage—from the 1923/1949 line, often considered the technical fences themselves as coincident with the Blue Line. So, when the IDF would venture north of its defensive positions for military landscaping purposes, Lebanon would often protest a violation of the Blue Line itself. This appears to be the genesis of the most recent incident, as UNIFIL found that no violation of the Blue Line had occurred.

When hopes were high in 2012 that an American compromise proposal for an Israel-Lebanon maritime separation line in the Mediterranean Sea—the so-called “Hof Line”—would be accepted by both parties and implemented, there was also hope that American mediation might come ashore to help resolve disputes connected to the 2000 Blue Line. Alas, Lebanese political instability blocked a maritime agreement that, if implemented, would be pouring natural gas revenues into cash-starved Lebanon today. And failure to implement a compromise deemed fair by both prime ministers at the time has left the Blue Line subject to gratuitous tension and occasional gunplay.

UNIFIL did well to defuse the latest episode. After 42 years it knows the drill. That its services are still required more than four decades after its “interim” deployment is regrettable. It is one symptom among many of opportunities routinely missed, decade after decade.

Ambassador Frederic C. Hof is Bard College’s Diplomat in Residence and a distinguished Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council.

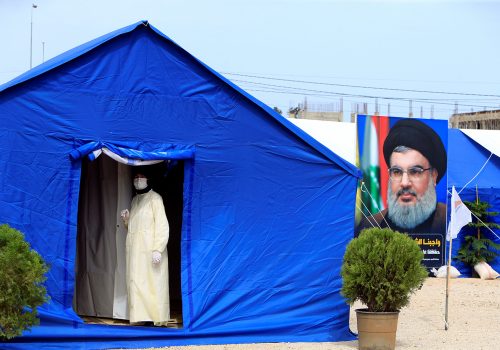

Image: A banner depicting Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah and an United Nation's post are seen in Lebanon from the Israeli side of the border, near Zar'it in northern Israel August 28, 2019 (Reuters)