Rising inflation is hurting Egypt’s economy. Will the country’s powerful military cede economic power to salvage it?

Egypt’s economy is submerged in an economic crisis. The prices of food and other basic commodities including housing and medical services have soared over the past few months as the country faces rising inflation. The inflation rate averaged 22 percent in December 2022—the highest rate the country has registered since 2017, according to the semi-official Ahram Online.

Analysts predict that inflation will continue to increase over the coming months, given the country’s limited resources in foreign currencies, which inflict further hardships on low-income households who are already struggling to get by.

This trend is alarming, considering that nearly 30 percent of Egyptians live below the poverty line. Rising anger over the unprecedented price hikes could also lead to a new wave of social unrest in the Arab world’s most populous country, with dire political and security implications for the entire region.

At the same time, the country’s foreign reserves have significantly fallen, reaching $34 billion in December 2022—just enough to cover about 5.4 months of Egypt’s imports, according to the Central Bank of Egypt. The pressure on the Egyptian pound has pushed the government to endorse the third devaluation of Egypt’s local currency in less than a year, reaching 32 Egyptian pounds against the dollar by midday on January 11 in the official market, before rebounding to 29.6 against the dollar the next day.

The latest devaluation was prompted by an agreement sealed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in December 2022 to offer Egypt the first tranche of a forty-six-month $3 billion rescue loan. The Egyptian government is hoping to use this loan to restore investors’ confidence in the faltering economy and to catalyze additional financing from regional and international partners. Exchange rate liberalization and the reduction of fuel and electricity subsidies are key pillars of the country’s reform program agenda, which has been endorsed by the government since 2016 in collaboration with the IMF.

While the country’s dire economic situation results from cascading global disruptions wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian war in Ukraine—which severely impacted Egypt’s vital tourism sector—some analysts suggest that government misspending is another key factor. Numerous mega infrastructure projects undertaken in recent years have strained the state budget while expanding the military’s role in the economy. This includes the New Administrative Capital, currently under construction outside Cairo.

At the end of December 2022, a post published by Egypt’s National Institute of Nutrition on its official Facebook page—and later picked up by state media—promoting “chicken legs” as an alternative “protein-rich” and “inexpensive” meal to help citizens cope with the latest wave of price hikes fueled public anger and an uproar on social media. The controversy over the provocative suggestion reached the parliament. At a public parliamentary session on January 3, MP Karim El-Sadat lambasted an official from the Ministry of Supplies who had spoken about the nutritional benefits of chicken legs on a television show, accusing the official of being “out of touch” with the reality of the current economic crisis.

“This, at a time when there is a shortage of basic goods and many commodities are beyond the reach of the ordinary citizen,” Sadat said. “We, as deputies, are left to face the wrath of citizens over soaring prices.”

The Egyptian Armed Forces, which have a competitive edge over private enterprises due to tax exemptions for the military, has cemented its economic power in the country in recent years. From hotels, gas stations, car manufacturers, pharmaceuticals, and infrastructure projects to the provision of goods and services, the military has steadily increased its involvement in multiple sectors of the economy, generating substantial revenue for army coffers from businesses that are either directly owned and run by the officers or through contracts provided to military-affiliated companies, leaving the private sector out in the cold.

To secure the IMF loan, however, Cairo has had to acquiesce to IMF demands to shrink the military’s overbearing role in the economy and increase that of the private sector as leveling the playing field between the public and private sectors has been promulgated by the Fund as “a critical structural reform to increase competitiveness.”

Promises aside, it will be difficult for Cairo to meet the IMF condition of pushing back the public sector and the military out of the economy. Despite President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s repeated promises to list public-owned firms on the stock exchange,” opening the door for private sector participation in state-owned enterprises,” there have been no real attempts to privatize military firms as of yet, indicating a possible pushback from within the military. Floating the shares of military-owned firms would mark a turning point for Egypt, where the financial value of army assets has remained under wraps and the military budget has long been shielded from public scrutiny.

Meanwhile, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, which face a growing Iranian regional threat, recognize that the collapse of Egypt’s economy and disintegration of Egypt’s military would pose an existential threat to their own countries; Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have both repeatedly stressed that “Egyptian security is an integral part of Arab security.” If Egypt’s economy were to fail, the ensuing political turmoil and lapse in security in Egypt would indeed spill over into Gulf countries. Therefore, key GCC countries have poured billions of dollars since the 2011 uprising—$92 billion to date, according to an unnamed official at the Central Bank—to stabilize the Egyptian economy and restore regional stability and security. Nevertheless, while the GCC bailouts have managed to stave off economic collapse in Egypt so far, they have fallen short of developing a sustainable economic system that can support Egypt in the long term.

Reluctant to pour more financial aid into Egypt’s seemingly bottomless economy, Egypt’s oil-rich Gulf allies are now looking to buy state assets that Cairo is putting up for sale in order to bridge its financing gap. The country hopes to attract $40 billion worth of investments over the next four years to build up its foreign reserves and ease its foreign debt burden.

But this is no win-win: while the government claims that the investments will consolidate Egypt’s position as one of the world’s leading investment destinations, the asset sales are a matter of grave concern to many Egyptians, since they perceive this as a sign of further erosion of their country’s economic and foreign policy autonomy.

As an alternative long-term remedy, Egypt must create a favorable investment climate, giving local businesses a level playing field. Unless that happens, Gulf investments will be of little value to Egypt and investors alike.

Shahira Amin is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and an independent journalist based in Cairo. A former contributor to CNN’s Inside Africa, Amin has been covering the development in post-revolution Egypt for several outlets including Index on Censorship and Al-Monitor. Follow her on Twitter @sherryamin13.

Further reading

Tue, Jun 28, 2022

Egypt is cozying up to Russia. It’s time for the US to step in.

MENASource By Shahira Amin

Egypt has, on several occasions, proved its mettle as a mediator between Israel and the Palestinians. Such support would also ensure Cairo's commitment to continuing the economic and political reforms it has started which are in the interests of both the US and Egypt.

Wed, Aug 10, 2022

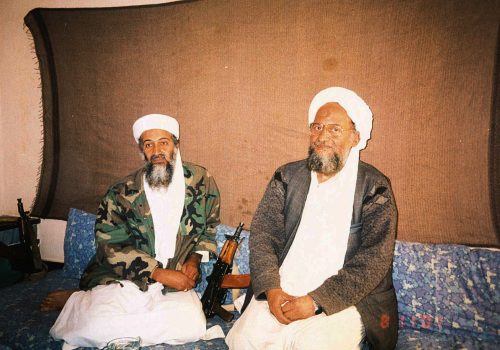

The founding head of al-Qaeda is dead. But radicalism continues to thrive in Egypt.

MENASource By Shahira Amin

The founding head of al-Qaeda is no longer, but it’s important not to forget that the terrorists that carried out 9/11 were born, raised, and radicalized in Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Wed, Jul 13, 2022

Biden’s Middle East trip is sending Iran an escalatory message. Here’s why.

MENASource By Shahira Amin

The flurry of diplomatic activity in the region ahead of Biden’s Middle East trip, is part of efforts by the GCC and Arab leaders to coordinate stances and forge a unified force against Iran.

Image: An Egyptian woman buys vegetables at a popular market in Cairo, Egypt, January 18, 2023. REUTERS/Hadeer Mahmoud