As the Syrian conflict enters its fourth year, the humanitarian costs continue to rise almost exponentially. The reported death toll from the civil war stands at more than 146,000, with more than 6.5 million displaced persons. Children have not been spared in the process. More than 10,000 have been killed, countless more injured, and millions are refugees or displaced within Syria. The impact of the war on the 5.5 million school-aged children in Syria will have profound effects on what the Syrian economy will look like in the future.

As the Syrian conflict enters its fourth year, the humanitarian costs continue to rise almost exponentially. The reported death toll from the civil war stands at more than 146,000, with more than 6.5 million displaced persons. Children have not been spared in the process. More than 10,000 have been killed, countless more injured, and millions are refugees or displaced within Syria. The impact of the war on the 5.5 million school-aged children in Syria will have profound effects on what the Syrian economy will look like in the future.

As a backdrop, consider the state of the Syrian economy prior to the uprising in March 2011 that then morphed into an all-out civil war. Syrian economic performance in the previous decade, while not stellar, was reasonably sound. During 2000-2010, growth averaged nearly 4.5 percent, inflation was running at less than 5 percent, and positive external balances led to a buildup of international reserves to $18.2 billion. The Syrian Pound (SYP) appreciated by an average of 2 percent a year against the US dollar, reaching SYP 47 to the US dollar in December 2010. Syrian nominal GDP reached $60 billion, with per capita income at nearly $3,000.

After the uprising, the following three years saw an almost complete collapse of the Syrian economy. The full extent of this collapse is difficult to measure since the government stopped reporting official economic statistics 2011—admittedly for good reason, as the figures would highlight the destruction taking place. Nevertheless, a number of unofficial estimates for various indicators can be pieced together to obtain an overall picture of economic developments during 2011-2013.

By all indications, the Syrian economy is in an acute state of distress. Real GDP is estimated to have fallen by 40-50 percent during 2011-2013, and continues to fall this year. The United Nations reports that unemployment is nearly 50 percent, half the population lives below the poverty line, and 9 million Syrians are in need of humanitarian and development assistance.

Furthermore, inflation in the last three years reached an estimated average of 80-100 percent per year, and the country has virtually run out of international reserves, holding a paltry $1-2 billion from the more than $18 billion it had at the beginning of 2011. Only the support received from Iran via a $3.5 billion credit line and from Russia through imports of raw materials and other inputs has kept the Central Bank of Syria from shutting its doors. As expected in these circumstances, the exchange rate depreciated from SYP 47 to the US dollar to SYP 206 by September 2013, and is currently hovering around SYP 150.

All in all, nominal GDP of Syria has dropped by half—from $60 billion to $30 billion—in the space of 3 years. Syria is now the second smallest Arab economy—smaller than Jordan (GDP $35 billion), Lebanon (GDP $45 billion), and Yemen (GDP $40 billion). It is only larger than Bahrain (GDP $28 billion), which has a population of only 1.3 million compared to Syria’s over 20 million.

While the civil war has clearly been the proximate cause of the economic collapse, international sanctions played a significant role by denying the country foreign exchange. The import ban imposed on the oil sector by the EU is probably the most significant sanction, and the additional ban imposed on the transport, financing, and insurance of oil exports severely restricts Syria’s access to new markets. As a consequence, oil production declined from 387,000 barrels per day (bpd), of which more than half was exported, before the sanctions to 14,000 bpd. Today, Syria has no oil exports at all and depends entirely on Iran for its fuel needs.

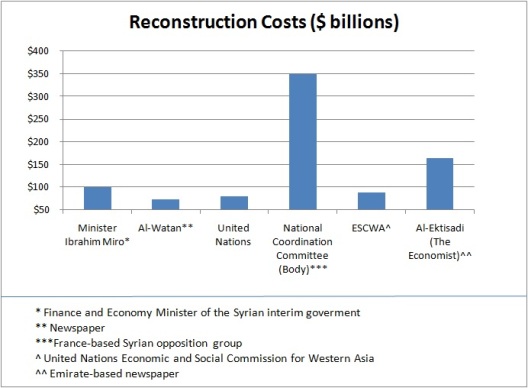

If the war were to miraculously end now, the reconstruction costs would be huge. Admittedly, these costs are hard to measure as a range of estimates in the chart shows. They could be anywhere from $80 billion to the high estimate of $350 billion put forward by the National Coordination Committee, a France-based Syrian opposition group.

These estimates are based primarily on estimates of the destruction of the country’s capital stock and infrastructure. Even Syrian Prime Minister Wael al-Halqi admitted to a figure of $31 billion—surely a serious underestimate. The UN puts the loss of capital stock at around $50 billion. Whatever the actual figure for reconstruction costs, it is safe to say that they would be enormous and there is no obvious source of financing to cover them.

Unlike Iraq and Libya, both of which faced post-war reconstruction costs of a similar magnitude, Syria cannot count on future oil revenues and will have to depend largely on the international community to provide financing. It is far from clear whether the international community will be ready to come up with the money, particularly if Bashar al-Assad remains in power. Iran and Russia are Assad’s only hope and neither have the resources to take on Syria’s large potential financial burdens.

If, somehow, the financing for reconstruction materializes, it will take years (possibly decades) for Syria to get back to its pre-2011 growth rates and level of economic development. Compounding the problem of the replacement of the capital stock is the lack of a skilled labor force. Here the civil war has played havoc on the potential labor supply. Having a large proportion of young Syrians that lack education and vocational skills because schools have been destroyed and the education system is almost totally dysfunctional will be a major constraint on potential growth.

The economic cost of a lost generation of young traumatized, injured, or displaced Syrians has to be factored into Syria’s future development. Syria has fallen to the bottom of all Arab countries on every generally recognized development indicator. Recovery will be a slow, drawn out process. From an economic standpoint, Syria will only be a relatively small player in the region for years to come. It will look back to the pre-2011 period as its glory days, hoping one day to return to that level of economic performance. It is not a high bar, but for Syria to get to it would be quite an achievement.

Mohsin Khan is a resident senior fellow in the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East focusing on the economic dimensions of transition in the Middle East and North Africa. Svetlana Milbert is the assistant director for economics at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Four young Syrian boys with toy guns in Azaz, Syria. (Photo: Christiaan Triebert/Flickr)