The irrefutable logic of numbers and the inevitability of reform in Iraq

On October 13, Iraq’s Council of Ministers endorsed the White Paper for financial and fiscal reform. While, on the surface, the paper might appear to be yet another economic reform package in response to a fiscal crisis brought about by falling oil revenues, the lofty goals are likely to be forgotten as soon as rising oil prices rescue the state from its current quagmire. However, the paper—a first for any Iraqi government—identifies the fault lines in the economy and the political system that fostered them. Without specifically stating so, it aims to upend the stagnant status quo by proposing to redefine the role of the state in the economy and society away from the prior model that prevailed during the 1970s, which mushroomed to unsustainable levels in the post-2003 war years.

A key target of the reform process and the root cause of Iraq’s financial and liquidity crisis is its structurally unbalanced budget—the vehicle through which the state has expanded and maintained its role in the economy and society. Among the first elements introduced includes real fiscal discipline, part of a long-term structural shift to the federal budget that is expected to be incorporated for the first time into the 2021 budget. This will affect the salaries and entire system of subsides, that will be gradually cut over a three year period, from a projected 25 percent and 13 percent respectively in 2020 estimated GDP, to 12.5 percent and 5 percent of 2023’s GDP. Another significant first is to reduce financial support to State Owned Enterprises (SOE’s) by 30 percent a year.

However, achieving this is fraught with difficulties, given the political sensitivities and vested interests in these two issues. This is because they were the tools through which the post-2003 order exercised its patrimonial role as a redistributor of the oil wealth in exchange for social acquiescence of its rule and, thus, any change would mark the start of the order’s unravelling.

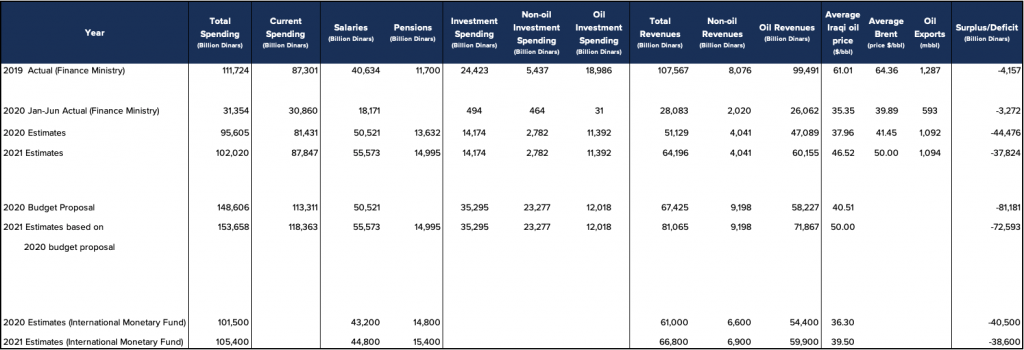

In a promising development, Iraq’s Finance Minister Ali Allawi noted in an interview following the paper’s endorsement by the Council of Ministers that, “There is less denial; before it was all denial.” This shift in attitude has come about with the slow realization that the current crisis is unlike others and a grudging acceptance of the White Paper’s main thrust: though the crisis brought on by the fall in oil prices due to COVID-19 was unforeseeable, the economy’s accumulated structural imbalances, compounded by demographic pressures, would have inevitably led to a similar economic and fiscal crisis. Furthermore, the White Paper asserts that the current crisis manifested itself in the budget’s un-resolvable quandary of a rising and a rigid current spending item versus variable and unpredictable oil prices (table below), as would happen in an inevitable future crisis.

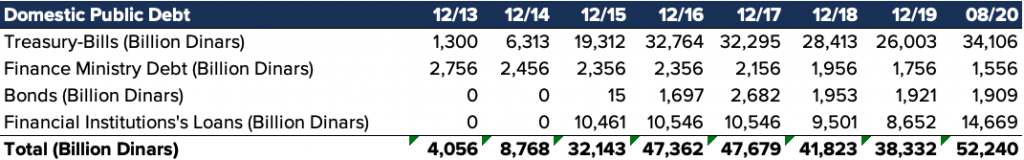

And, so, irrespective of the different assumptions made for 2020 and 2021, the federal budget will incur a significant deficit that it cannot finance as it did in the past (i.e. through a combination of accumulating arrears to the domestic private sector and to International Oil Companies (IOC’s) and through foreign and domestic borrowing). The key departure from the past is that accumulating arrears to the domestic private sector will amplify the COVID-19 stresses on the domestic economy, while foreign support is unlikely given the high spending undertaken so far, and likely to increase by governments worldwide—estimated by the International Monterey Fund (IMF) at $11.7 trillion or 12 percent of estimated global GDP for 2020—to support households and businesses to combat the negative effects of the pandemic. Moreover, domestic borrowing, which accounted for the bulk of borrowing during the 2014-2017 twin crises of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and the fall in oil prices, cannot be relied upon in the current crises as debt levels are now higher than they were at the heights of the last crises (table below).

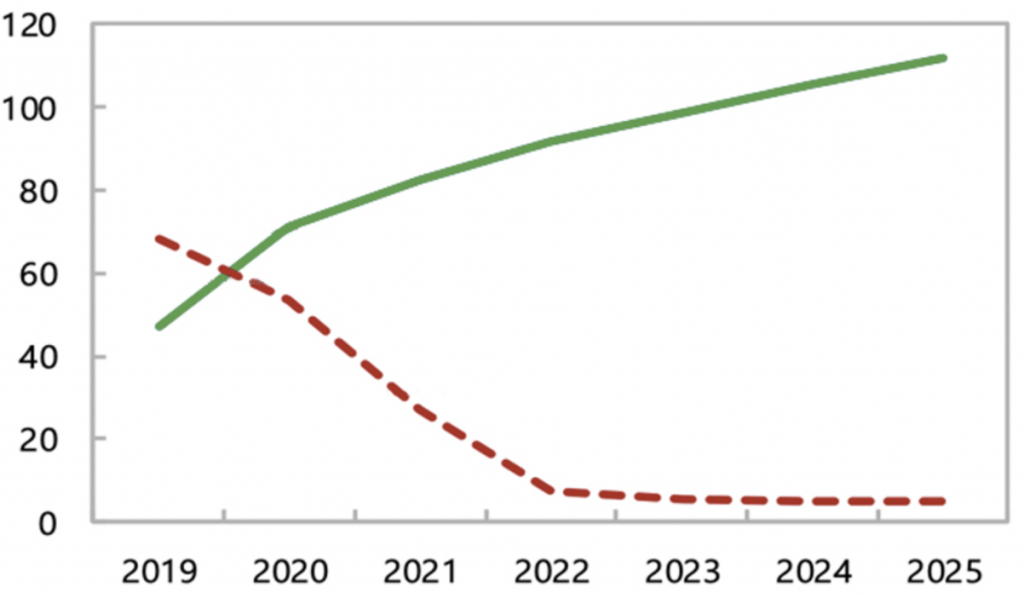

Ultimately, without implementing the reforms proposed by the White Paper, the only available route is indirect monetary financing by the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI), which will inevitably lead to the erosion of its reserves. Those reserves could decline to dangerously low levels in only nine months, prompting a currency crisis and a likely forced devaluation of the Iraqi dinar (chart below).

While a devaluation is seen by the political elite as the preferred solution for stretching the state’s diminishing oil revenues to cover its expenditures—particularly the payments of salaries and pensions—the paper argues that this will soon unravel as prices for goods and services would rise in lockstep with the devaluation. This would amount to an increase in the cost of living and, thus, lower the living standards of the majority of the population—estimated at 40.2 million for 2020—given the country’s high dependence on imports to satisfy consumption of goods and services.

While the outlook and prognosis for Iraq seems grim, it is this grimness that finally promises to unlock Iraq’s potential and is the only effective guarantor for the success of reform. The White Paper’s recommendations, while difficult to implement, are technically achievable. The real obstacle to reform—now, as in the past—is the lack of political will to act on reform or, more accurately, the strong political will to preserve the status quo. However, the severity of the current crises has closed the door on the half-hearted ad hoc measures of the past, leaving no option other than structural reforms.

Ahmed Tabaqchali is the Chief Investment Officer of Asia Frontier Capital’s Iraq Fund. He is also a senior fellow at the Institute of Regional and International Studies (IRIS) and an adjunct assistant professor at the American University of Iraq (AUIS).

Image: Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi speaks during a meeting with security leaders, in Basra, Iraq August 22, 2020. Picture taken August 22, 2020. Iraqi Prime Minister Media Office/Handout via REUTERS