Tony Pfaff: The ethics of proxy relationships applies to everyone

Dr. C. Anthony Pfaff is the research professor for strategy, the military profession, and ethics at the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. A retired Army colonel and Foreign Area Officer (FAO) for the Middle East and North Africa, Pfaff has served as director for Iraq on the National Security Council. His last active-duty posting was senior army and military adviser to the State Department from 2013–2016, where he served on the policy planning staff advising on cyber, regional military affairs, the Arab Gulf region, Iran, and security sector assistance reform.

Our MENASource editor, Holly Dagres, had the pleasure of sitting down with Dr. Pfaff on March 7 to discuss his most recent book, Proxy War Ethics: The Norms of Partnering in Great Power Competition, and its implications for US foreign policy.

MENASOURCE: What compelled you to write a book about proxies?

DR. TONY PFAFF: Great question! This project originally started as a presentation for the US Naval Academy’s Post-Doctoral Fellowship Program back in 2017. The director of the program was interested in exploring the topic, but there was not much at the time written on it. What got me interested was not only that this is an under-covered area of research and policy, but the lack of understanding regarding governing proxy relationships sets us up for significant moral failure and hazard.

Part of the problem is that “proxy” is often used pejoratively. To have a “proxy” is to be exploitive and to be a “proxy” is demeaning. The difficulty with that view is that “proxy” describes a structure of relationship that exists independently from the label. It might make political sense to call a “proxy” an “ally,” but that does not change the political reality. So the first step in understanding how to govern these relations is understanding their structure, which is much of the first chapter in the book, where I examine the differences between alliances, partnerships, and proxies.

Put simply, what differentiates proxies from other relationships is the indirect nature of the benefit for the sponsor, the extra-constitutionality of the proxy, and divergent interests. Under such a principle-agent arrangement, the sponsor enables the proxy to fight while the proxy enables the sponsor to minimize its risks. It is not difficult to see how proxies get a bad name. Even where sponsors and proxies share an interest, they often are not willing to pay the same price to achieve it. As a result, the history of proxy wars is littered with proxies who were “hung out to dry” by sponsors or sponsors that are dragged into a quagmire, escaping from which is costly. Perhaps more importantly, the presence of a sponsor can make nonviolent but politically costly alternatives to war less attractive, leading to wars that may have otherwise not happened. So, there is a lot to uncovering proxy relationships and trying to explain how to manage and govern such relationships.

MENASOURCE: Were there any things that surprised you or really stood out to you during your research that you were not aware of?

DR. TONY PFAFF: The understanding of proxy as a structure, and showing how that impacts the application of the just war tradition, I thought was illuminating. Also, the ubiquity of moral hazards identified in the book in the history of proxy wars really underscores the need for more robust international norms. What you often see in that history is that even well-meaning actors who are willing to self-regulate get caught up in the logic of the proxy relationship and cause all sorts of harm. The United States, for example, did condition assistance to El Salvador in the 1980s on conformity to the law of armed conflict and holding violators accountable—but those conditions were waived when rebel forces achieved any level of success. In Afghanistan, providing Stinger missiles seemed like a good idea—though there is some controversy over how impactful they really were—until they started showing up all over the world.

MENASOURCE: Which countries are the top sponsors of proxies today? Some obvious countries come to mind, but I wonder if there are ones we have missed.

DR. TONY PFAFF: Well, the Oscar for “Best Use of Proxies” probably goes to Iran, which has successfully utilized proxies to advance its national security objectives, generally at very little risk to itself, in part because there is very little in the way of international law or norms—formal or informal—that would allow the international community to hold it responsible. But…many international actors, including the United States, have relationships that more resemble a proxy structure than an ally or partner.

That brings me to another important point. “Proxy,” “ally,” and “partner” are ideal descriptions. Any particular relationship may exhibit traits of more than one; it is not all or nothing. So, you can have an element where there is just enough indirect benefit or where there is just enough risk mitigation and cost-cutting that something that you might actually get genuinely described as a partnership or alliance is still prone to the same kind of moral failure and hazard more obvious proxy relationships are.

So it would be naïve to look at US support to Ukraine or Saudi Arabia in Yemen and not count them as some kind of proxy relationship. This doesn’t entail that the United States is wrong for providing this support or that Ukraine or Saudi Arabia are demeaned for accepting it. However, that support raises the kinds of concerns that one would expect from a proxy relationship. While the United States and Ukraine may share an interest in repelling Russia’s invasion, they are not willing to pay a similar price to achieve it. That’s because while these interests are shared, they are not fully aligned. So, there is a risk that limiting US and NATO support will place Ukraine in a position where it ends up with the same result had it not fought at all, but at a much higher price.

Having said all that, I think Iran’s use of proxies is much more central to how it generally meets its security objectives, whereas for actors like the United States and even Russia, such relationships may complement other means, but they are not as reliant on them as the Iranians seem to be.

SIGN UP FOR THE THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

MENASOURCE: It is interesting you mention the United States because the term “proxy” is typically associated with a negative connotation. Do you think that there is a misunderstanding of the nomenclature?

DR. TONY PFAFF: Sometimes I feel like the kid in The Sixth Sense film who saw dead people. Except I see proxies. But as I mentioned, the word “proxy” describes a particular structure of relationships that I distinguish from alliances and partnerships. So yes, the United States has proxies. The Russians have proxies. The Iranians have proxies. The Chinese use proxies. Ukraine is a good example. Saudi Arabia is a good example. We supported Saudi Arabia against Houthis in Yemen for a very long time before we got directly involved as a way of containing Iran. That is the structure of a proxy relationship.

My point is that engaging in such relationships is not necessarily exploitative or otherwise wrong. In this view, proxy relationships are just another way actors mitigate cost and risk. What matters are the norms they employ that govern them.

So, for me, the word “proxy” is morally neutral. Supporting Ukraine in its fight against Russia is a just cause and fits under the traditional “just war” rubric of defense of another. However, because we are doing it indirectly, we are mitigating our own risks. Thus, you start seeing those proxy dynamics creep in. For example, why are we having discussions about terminating support to Ukraine? Because we can. In an alliance where actors take on similar costs and risks against a common threat, it would be much harder to have that discussion. If we had skin in the game, if we were fighting alongside the Ukrainians, with US troops engaged alongside the Ukrainians, quitting would be a whole lot harder.

I don’t think there is anything wrong with our support for Ukraine or Saudi Arabia, for that matter. But that support forces us to ask questions, such as when it is permissible to withdraw it. It also forces us to consider to what extent we are responsible for how that support is used. When Saudi operations in Yemen raised discrimination concerns, we were arguably obligated to, and to an extent did, modify our support to address those concerns.

But it isn’t just about regulating our actions. Absent adequate international norms, it is difficult to rein in more abusive practices, such as Iran’s. The problem is traditional just war theory, even as it is reflected in international law, does not fully account for the effect the introduction of a sponsor has. Moreover, there is very little with which to hold sponsors accountable.

The reason accountability is important here is because the structure of the relationship frequently discourages it. For example, Nicaragua took the United States to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) over its support to the Contras, who had arguably committed a number of law of war violations in their resistance against the Sandinistas. The court decided that because no organ of the United States ordered those violations, even though the court did find that the United States provided a manual that appeared to advocate illegal practices like assassination, the United States was not accountable. What is interesting is that the manual was intended to rein in the Contras’ abuses.

The problem with both these standards is that they disincentivize sponsors to hold proxies accountable. The more a sponsor gets involved in trying to control proxy behavior, the more likely they could be accountable for it. So, it is better, as Iran did for Hamas, to provide resources and training but little else. This is why I think more robust international norms would be beneficial. As it stands, not only would Iran not likely be legally responsible for Hamas’s atrocities on October 7, 2023, or Houthi attacks against Red Sea shipping for that matter, if the United States or Israel decided to attack Iran directly in response, they would arguably, at least from a legal point of view, be the aggressor.

MENASOURCE: Are there any other examples of proxies being held accountable in the context of international law? Given how they are set up, it seems like a really hard thing to do.

DR. TONY PFAFF: There are two precedents that are usually cited in this regard. One is the ICJ ruling on Nicaragua, which I just mentioned, that applied a standard of “effective control.” The other is in Yugoslavia, where it applied a standard of “overall control.” There, the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia found that the Yugoslav government was accountable for Serbian Army actions in Bosnia since the Serbian and Yugoslav armies effectively shared personnel, paid salaries, provided logistics, and so on. This standard, however, basically says that for an actor to be accountable for a proxy’s action, they pretty much have to assimilate them into their constitutional structure to the extent they are not really a proxy anymore.

There is also the Arms Trade Treaty, which prohibits transfers of weapons where the exporting party knows that the receiving party will use them to “commit genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Convention, or attacks against civilians.” The difficulty here is that Russia, Iran, or the United States are not parties to the treaty—despite the fact the United States was largely responsible for drafting the treaty—and even for those who are, enforcement is pretty weak. I should note that for the United States, many of the provisions in the treaty are already a part of US law. Israel is a signatory, but it has yet to ratify it.

MENASOURCE: What is your read on Tehran’s use of proxies?

DR. TONY PFAFF: Well, Iran’s use of proxies is more central to how it operates than other similar actors. It is not the only thing, of course, but it certainly prefers asymmetric to symmetric means. Ballistic missiles, for example, are also a security pillar because they are hard to defend against.

So, Iran uses [proxies] because they are a great way to mitigate cost and risk, whatever their actual objectives are—until they are not. The case of Iran actually illustrates the pros and cons of proxy use. For example, one of its proxies, Kata’ib Hezbollah, attacked a facility in Jordan, killing three US soldiers and wounding several others, who were supporting the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). While there has been a tit-for-tat exchange going on for a while in Iraq and Syria, attacking US troops in Jordan was a significant escalation, and one it appears Tehran didn’t intend. After the attack, Kata’ib Hezbollah put out a statement that, while it certainly didn’t apologize for the attack, did say it would not retaliate against any subsequent US attacks and that Tehran had no prior knowledge of the attack. So, this could certainly have been a case of a proxy dragging a sponsor into a deeper, more costly conflict.

MENASOURCE: Can Tehran be held accountable for its proxies?

DR. TONY PFAFF: Absent a consensus that providing assistance used in an atrocity could make one, in some way at least, accountable for it, I’m not sure how. Of course, one can always impose non-lethal costs such as sanctions and so on, but those typically haven’t been effective.

MENASOURCE: What do you think policymakers in Washington get wrong about proxies?

DR. TONY PFAFF: The first part goes back to what I started talking about at the beginning. Proxy refers to a particular structure and to ignore the effects of that structure is to risk moral failure and hazards, which I discuss in detail in the book. Moral failure occurs, for example, when sponsors facilitate wars that may not have otherwise needed to happen, and especially when they withdraw support in ways that leave the proxy worse off for having fought in the first place. That doesn’t mean support should be open-ended or unconditioned. However, it is important to be upfront about what those limits and conditions are so all actors can make better informed decisions.

Ukraine is a great example. Had we not supported it—and I am not saying we should not have—at worst, there would be a new Russia-aligned government in Ukraine. At best, Ukrainians would have been forced to settle earlier on. They may have lost Donbas, they may have lost Crimea, but they may have been able to come to an accommodation with the Russians, and the fighting would have been over much sooner. The fact we supported them allowed them to continue their fight, which made settlement less attractive. That by itself is not a bad thing. As I noted previously, they have a just cause. However, if withdrawing that support encourages or enables Russia to achieve a more complete victory, then I think there is a moral failure. I think once an actor provides support, it should continue absent bad actions by the recipient, physical limitations of the sponsor, or a conflict with a higher priority.

Holly Dagres is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs and editor of the Atlantic Council’s IranSource and MENASource blogs. Follow her on X: @hdagres.

Further reading

Wed, May 24, 2023

The US needs to be proactive in order to break its escalatory cycle with Iran

MENASource By C. Anthony Pfaff

Here we go again. On March 23, Iran-backed Iraqi militias launched a drone attack that killed an American contractor and wounded another, as well as twenty-four US military personnel. The attack feels very much like a repeat of the one in December 2019, which also killed a US contractor and led to an escalatory cycle, […]

Tue, Oct 24, 2023

The legal challenges in holding Iran accountable for supporting Hamas

New Atlanticist By C. Anthony Pfaff

Under current international law, a state actor may only be responsible for the actions of a proxy if it directs the proxy to take those actions or knows that the provided material would be used to commit certain crimes.

Fri, Nov 4, 2022

Iraq has a new government. The United States would benefit from broad engagement with all Iraqi stakeholders.

MENASource By C. Anthony Pfaff

Such an approach will typically yield modest results, but these results can accumulate and place the United States in a better position.

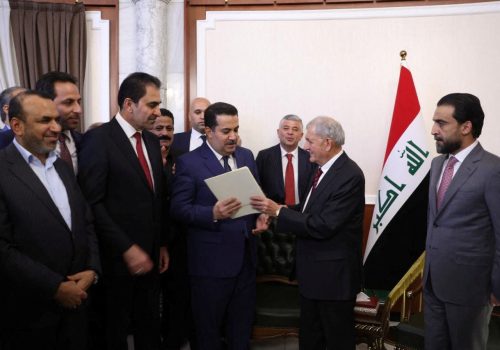

Image: C. Anthony Pfaff during an interview with the Atlantic Council on the 20th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq (via Atlantic Council).