The pride, stature and global spotlight that comes with holding a major international meeting often becomes a factor influencing the host country’s behavior. As China is hosting the APEC leaders’ meeting, Beijing clearly wants to be seen as a gracious host and a cooperative partner.

The pride, stature and global spotlight that comes with holding a major international meeting often becomes a factor influencing the host country’s behavior. As China is hosting the APEC leaders’ meeting, Beijing clearly wants to be seen as a gracious host and a cooperative partner.

The APEC meeting occurs in an Asia-Pacific where tensions have been mounting over territorial disputes, where competing trade agreements are in contention, and where, for the first time in several decades, many fear that regional stability may be at risk.

Against this backdrop, it appears that APEC may showcase a recalibration of Chinese policies in the region in an effort to bolster regional stability.

In recent weeks we have seen high-level Sino-Vietnamese diplomacy reaching accords on military-to-military ties aimed at better managing maritime differences as well as efforts to reset the bilateral relationship politically. Chinese President Xi Jinping recently told a senior envoy from Hanoi, “I hope the Vietnamese will make joint efforts with the Chinese to put the relationship back on the right track of development.”

In regard to Japan, the stage was set for a substantive Xi-Abe meeting by a November 7 agreement to reset the relationship and resume dialogue in the “political, diplomatic and security fields.” Japan acknowledged that the two sides held differing views on tensions around the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and agreed to create crisis management mechanisms. Japan also agreed to “face history squarely” and to “make an effort to build a political relationship of mutual trust.” That agreement suggests that the territorial dispute will not impede economic and other mutually beneficial elements of the Sino-Japanese relationship.

US-China relations are also likely to move forward with the Xi-Obama summit on the margins of APEC. Efforts to define what is meant by a “new type of great power relationship” should emphasize areas of cooperation like climate change, energy security, counterterrorism and anti-IS action, a bilateral investment treaty, and new trade accords.

Both sides have also been discussing new military confidence-building measures aimed at reducing the risk of accidental air and sea clashes, which when adopted, may help diminish mutual distrust. The US hopes such steps will lead to a larger process of defining a Sino-US framework for strategic stability.

While there has been some struggle over the nature of a potential free trade area in the Asia-Pacific, a long-time APEC goal, quiet diplomacy appears to have sorted out differences.

One obvious way to address the two competing trade arrangements – the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Sino-centric Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – would be to begin talks on how to harmonize them. Several members of TPP are also in RCEP, so there is a clear logic to integrating the two.

Moreover, though the US has regrettably not stressed it, China can join the TPP whenever it is ready to implement it. As China pursues ambitious economic reforms, it may view the standards required in the TPP as helpful – this was the case in the 1990s, when Beijing used its WTO ascension to facilitate reforms.

There has also been tension over China’s proposed new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which the US has opposed. But no one questions Asia’s growing need for infrastructure investment, and the US has offered no alternative. It would do better to discuss how the new bank might operate and complement the Asian Development Bank and World Bank.

But some are asking whether this is part of an ongoing trend of China adjusting its foreign policy to improve regional stability and reassure its neighbors or if it is more short-term in nature.

The last thing Asian nations want is to have to choose between the US and China. If APEC-related diplomacy brings the US and China a step closer to accommodating each other’s basic interests, it will be welcomed by all in the Asia-Pacific region.

Robert Manning is a senior fellow of the Brent Scowcroft Center for International Security at the Atlantic Council and its Strategic Foresight Initiative. He served as a senior counselor to the Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs from 2001 to 2004, on the US Department of State Policy Planning Staff from 2004 to 2008, and on the National Intelligence Council Strategic Futures Group, 2008-2012.

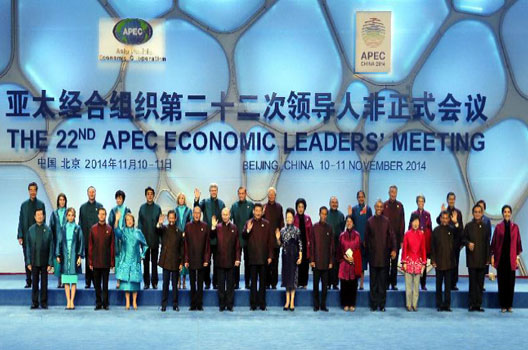

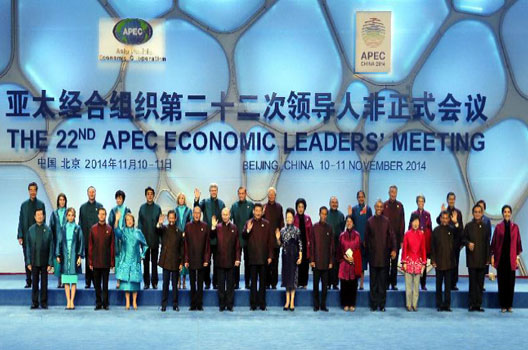

Image: 2014 APEC Summit in Beijing (Official summit photo)