A great power that allows itself to be preoccupied only with the problems of today is likely to end up mired in the conflicts of yesterday. A great power must be guided by a longer-range strategic vision.

For the United States, the central challenge over the next several decades will be to revitalize itself while promoting a larger West and accommodating China’s rising global status.

A successful U.S. effort to enlarge the West, making it the world’s most stable and democratic zone, would seek to combine power with principle. A cooperative, larger West—extending from North America and Europe through Eurasia (by eventually embracing Russia and Turkey), all the way to Japan and South Korea—would enhance the appeal of the West’s core principles for other cultures, thus encouraging the gradual emergence of a universal democratic political culture.

At the same time, the U.S. should continue to engage the East. If the U.S. and China can accommodate each other on a broad range of issues, the prospects for stability in Asia will be greatly increased. That is especially likely if the U.S. can encourage a genuine reconciliation between China and Japan while mitigating the growing rivalry between China and India.

To have the credibility and the capacity to act effectively in both the western and eastern parts of Eurasia, the U.S. must show the world that it has the will to reform itself at home. Americans must place greater emphasis on the more subtle dimensions of national power, such as innovation and education.

For the U.S. to succeed as the promoter and guarantor of a renewed West, it will need to maintain close ties with Europe, continue its commitment to NATO, and welcome into the West both Turkey and a truly democratizing Russia. To guarantee the West’s geopolitical relevance, Washington must remain active in European security. It must also encourage the deeper unification of the European Union: The close cooperation among France, Germany and the United Kingdom—Europe’s central political, economic and military alignment—should continue and broaden.

It is not unrealistic to imagine a larger configuration of the West emerging after 2025. In the course of the next several decades, Russia could embark on a comprehensive law-based democratic transformation compatible with both EU and NATO standards. The ongoing public demonstrations in Russia signal, already, the emergence of a young middle class that is increasingly internationalist and aware of its civic rights. Turkey, meanwhile, could become a full member of the EU. Both countries would then be on their way to integration with the transatlantic community. But even before that occurs, a deepening geopolitical community of interest could arise among the U.S., Europe (including Turkey) and Russia.

If the U.S. isn’t successful in promoting the emergence of an enlarged West, dire consequences could follow: Historical resentments could come back to life, new conflicts could arise, and shortsighted competitive partnerships could take shape. For example, Russia could exploit its energy assets and reawaken its imperial ambitions by absorbing Ukraine. With the EU passive, some European states such as Germany or Italy may seek accommodations with Russia out of economic self-interest, while France and the U.K draw closer and Poland and the Baltic states desperately plead for additional U.S. security guarantees. The result would be a splintered and increasingly pessimistic West.

In Asia, the U.S. role should be that of regional balancer and conciliator, replicating the role played by the U.K. in intra-European politics during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The U.S. can and should help Asian states avoid a struggle for regional domination by mediating conflicts and offsetting power imbalances among potential rivals.

In doing so, it should respect China’s special historic and geopolitical role in maintaining stability on the Far Eastern mainland. Engaging with China in a dialogue regarding regional stability would not only help reduce the possibility of U.S.-Chinese conflicts but also diminish the probability of miscalculation between China and Japan, or China and India—and even at some point between China and Russia over the resources and independent status of the Central Asian states. Thus America’s balancing efforts in Asia would ultimately be in China’s interest as well.

At the same time, the U.S. must recognize that stability in Asia can no longer be imposed by a non-Asian power, least of all by the direct application of U.S. military power. The guiding principle of U.S. foreign policy in Asia should be to uphold U.S. obligations to Japan and South Korea while not being drawn into a war between Asian powers on the mainland.

Zbigniew Brzezinski was U.S. national security adviser from 1977-81 and is a member of the Atlantic Council’s International Advisory Board. This article is adapted from an essay in the January/February issue of Foreign Affairs and originally appeared on The Wall Street Journal online.

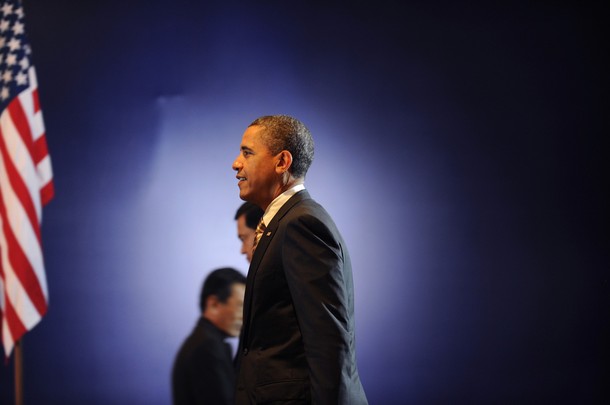

Image: obama_asean.jpg