As Starmer visits the White House, the US-UK ‘special relationship’ must look forward

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s visit to the Oval Office on Friday comes at the end of a significant week for US-UK relations.

Last weekend, the heads of the US Central Intelligence Agency, Bill Burns, and the UK Secret Intelligence Service, Richard Moore, wrote a joint column for the Financial Times reaffirming the readiness of their two agencies to stand together against “unprecedented” threats to their countries’ security and way of life posed by hostile states and actors. Burns and Moore also appeared together for a public event in London to drive home the message.

On Tuesday, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was in London seeing the UK foreign secretary, David Lammy, and the prime minister to discuss the crises in Gaza—which Blinken has been indefatigably trying to resolve—and in Ukraine. On Wednesday, Blinken and Lammy were in Kyiv to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

In the White House on Friday, Starmer and US President Joe Biden will be adding substance to a new strategic dialogue on foreign and security policy announced last week by the White House. There will be much to say on Russia and Ukraine, of course, and about Israel, Gaza, and the related issue of how to handle Iran. But I would expect the two leaders also to want to talk about China, foreign interference in election campaigns, and perhaps how the United Kingdom intends to rebuild its European relationships.

No doubt the Democrats will also be interested in any tactical tips Starmer may have for how to win a general election.

It was during and immediately after World War II that then Prime Minister Winston Churchill first popularized the description of the US-UK bond as a “special relationship.”

After a chaotic few years, during which the United Kingdom had five prime ministers in six years and was largely absent from effective diplomacy while it wrestled with the consequences of the 2016 Brexit referendum, the new Labour government is aiming to reset relations with neighbors and allies.

That is good news, even if the UK-US relationship is already on sounder footing than most. Britain and the United States have played a leading role in helping Ukraine resist Russian President Vladimir Putin’s illegal and unprovoked invasion. They have shot down Iranian drones and missiles targeting Israel and have together hit back against Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea.

Their shared, declassified intelligence exposed Putin’s deceit and aggression. Together, they are working to counter attempts to undermine democracy with disinformation and lies orchestrated by corrupt autocrats alarmed at the prospect of democracy and freedom taking root among their own subjects.

The United States and United Kingdom are founder members of NATO. This coming Sunday, the Australia-United Kingdom-United States partnership, also known as AUKUS, will mark three years. It has extended US-UK cooperation deeper into the Indo-Pacific region, at a time when all three countries have good reason to be concerned about China’s aggressive diplomacy.

Trade and investment links remain as strong as ever. There is no need for the comprehensive free trade agreement advocated, unrealistically, by Brexit supporters hoping to compensate for the business that the United Kingdom lost with the rest of Europe when it chose to leave the single market.

It was during and immediately after World War II that then Prime Minister Winston Churchill first popularized the description of the US-UK bond as a “special relationship.” At a time of great geopolitical uncertainty, Churchill warned in his speech at Fulton, Missouri, in March 1946 that an “iron curtain” had descended across Europe, and that the dark ages could return if democracies lowered their guard. In other words, the special relationship should not rest on what it had achieved so far; it should stay focused on what is to come. Whoever wins the US presidential election on November 5, the special links and shared values between the United States and United Kingdom will remain indispensable to their future prosperity and security.

Sir Peter Westmacott is a distinguished ambassadorial fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a former British ambassador to the United States.

Further reading

Thu, Jul 11, 2024

UK foreign secretary: Why NATO remains core to British security

New Atlanticist By

With a return of war to Europe and security threats rising, strengthening Britain’s relationships with its closest allies is firmly in the national interest, writes UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy.

Fri, Jul 5, 2024

Experts react: Labour is back. Here’s what to expect from the new UK government.

New Atlanticist By

Our experts outlined incoming Prime Minister Keir Starmer's priorities and the party's vision for the UK's role in the world.

Wed, Feb 28, 2024

After 14 years in opposition, what might a Labour foreign policy look like?

New Atlanticist By Francis Shin

UK Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy outlined a doctrine of "progressive realism" drawing on the Labour Party's past.

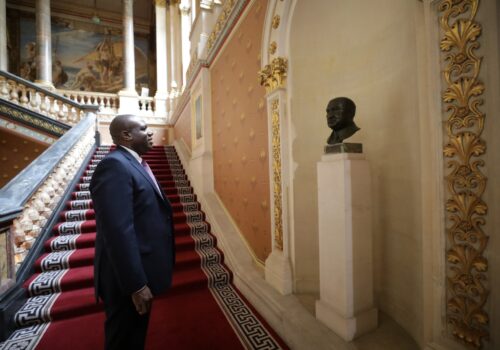

Image: Britain's Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer meets US President Joe Biden at the White House in Washington DC, during his visit to the US to attend the NATO 75th anniversary summit, July 10, 2024. Stefan Rousseau/Pool via REUTERS