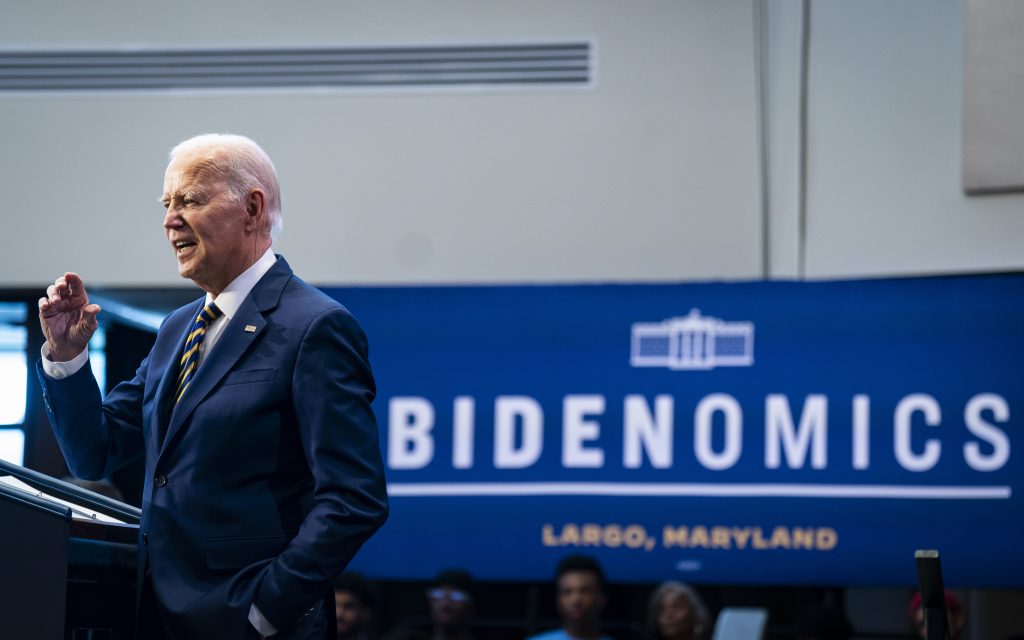

Since walking away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017, the US global economic playbook has been out of kilter. In the ensuing years, US leaders have worked to revive national manufacturing, but all too often they have only managed to manufacture new slogans. These slogans range from the Trump administration’s “Make America Great Again,” which weaponized tariffs and border controls, to the Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” and “Bidenomics,” which is perhaps the least defined, offering no clear organizing idea for US economic leadership. “Under Bidenomics, we’re going to make sure America’s future is made in America,” US President Joe Biden declared at the White House on Monday, dropping another slogan in for good measure. And who could forget “de-coupling,” “de-linking,” “de-risking,” “on-shoring,” “near-shoring,” and “friend-shoring”? If only the economic race with China were to be won by words, the United States would have it made.

A relatively recent addition to this list is “small yard, high fence,” rolled out out by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at a speech in April at the Brookings Institution. Sullivan began by defining the phrase in the context of targeted restrictions on critical technologies with national security concerns. That alone seems unremarkable, but in the rest of the speech he plowed into the widely discussed ills of the free market global economy, calling for greater government intervention. His analysis would have been more balanced and forceful if he had devoted equal time to the failings of well-intentioned government meddling in economies. However glibly articulated, state interventions are rarely a precision instrument—or a “small yard.” Much more often they are a blunt bulldozer, predisposed to overreach and waste. Green and progressive subsidies labeled as the Inflation Reduction Act are a case in point.

Sullivan’s “yard and fence” mantra invites a world full of fences of varying heights, protecting yards of uneven size. Ostensibly nestled within “middle class diplomacy,” Sullivan’s slogan hearkens back to protectionist mercantilist policies underlying the scramble for resources and militarization preceding the world wars of the twentieth century. After persuading Europe and Japan over decades to be like the United States in embracing free markets with reduced state involvement and protection, the United States now merrily outdoes them in both. And for the cherry, it invites them to follow suit.

The United States, instead of hiding behind its own fences, is better served rallying the world in fencing off Chinese economic coercion, distortion, and predation. Recent Group of Seven (G7) and Group of Twenty (G20) pronouncements represent a promising start, including the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor. The approach requires the United States to lead in both action and words to shape the world rather than retreat behind its oceans if the world is not to its liking.

China is the leading trade partner for more than 120 nations. Focusing solely on a better bunker strategy is short-sighted and self-defeating. The United States’ interests are best served when restructuring the world in its image and to its benefit. Allowing Beijing to bind three-quarters of the world’s nations to its economy would enable Chinese circumvention and subversion of international rules and imperil the hegemony of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. It would afford China a stronger hand at shaping future economic rules and standards. The prosperity of American farmlands and energy fields, of Silicon Valley and Wall Street, depends on the United States leading the global economy, not retreating behind fences.

US military superiority and political heft is directly linked to its economic preeminence. US leadership is vital in building regional security alliances across the Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific, areas that are seeing a welcome increase in convergence and coordination. Paradoxically, the instrumental US leadership in building and binding security alliances around the globe is conspicuously absent in the economic sphere. This overreliance on security alliances without concomitant economic alliances overtly militarizes the United States’ China policy, when the foundational conflict between Washington and Beijing is that of asymmetrical economic competition. To prevail against China, the United States needs to forward deploy both its economic and military alliances and assets. A lesson taken to heart in military matters is merrily discarded in economic statecraft. A retreating global economic posture vis-à-vis China cedes the global trading architecture to Chinese machinations.

Three ways to think outside the fence

As the United States rallies Europe to secure Ukraine’s sovereignty, backs Israel’s right to defend itself while pursuing regional normalization, and invests in military capacities to go clear across the Pacific to safeguard Taiwan, so it should forward deploy its economic advantages to rally, bind, and force multiply its interests with those of its allies in forestalling Chinese economic malfeasance. Three lines of effort should be prioritized in such an endeavor.

First, expeditiously establish rules for the global digital economy—including artificial intelligence—that favor free-world interests and values. A lack of an agreed domestic regulatory framework hampers the United States’ assertive global leadership. It relegates rulemaking instead to others, including Europe. Sustaining US preeminence in cloud connectivity, global internet, artificial intelligence, and financial markets requires it to lead from the front. It is imperative that the United States gets domestic digital governance done and rallies the world around it rather than settle for a suboptimal outsourced product.

Second, aggressively develop capital markets in emerging nations to better deploy private capital. Capital markets with macroeconomic stability and apt financial regulatory frameworks are integral to prosperous societies. They allow for efficient allocation of national savings to optimal private sector growth opportunities. The United States’ capital markets and the strength of the dollar are emblematic of the power of free enterprise. The world’s nations, including China, aspire to invest in them. The best antidote to Chinese state planning such as its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is to aggressively deploy the full force of US financial markets to address the infrastructure and economic growth demands of emerging nations. Even a half-successful deployment of such a strategy would outperform and overwhelm the Chinese BRI.

Third, reposition regional trade frameworks to advance commerce and trade with the United States and its allies rather than with China. The United States has an opportune window to counter the disruption to global supply lines caused by China’s draconian security laws used to target foreign companies and executives. Going forward, global trade—in all its neologisms of friend- and near-shoring, resilient and trusted supply chains, etc.—will be buoyed by strong regional arrangements among trusted partners.

The United States should engage, lead, and bind these trusted free and open trade arrangements as force multipliers of its own economic interests and outreach. To start, the United States should speedily seek convergence between its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity and the Japan-led Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership before China makes further inroads in the Indo-Pacific through its Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

Additionally, the United States should lead the effort to update and expand the G7 to a G10 by including the leading Indo-Pacific free economies of India, South Korea, and Australia. Concurrently, the United States should pursue creative ways of extending the proven benefits of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement to its economy in similar arrangements with strategic nations across Latin America and the Caribbean. Additionally, it should further energize the US-EU Trade and Technology Council to not only enhance bilateral trade and technology cooperation but extend this bilateral cooperation in third countries, particularly in Africa. Learning from the past, it is important to enact domestic policy instruments to ensure that the benefits from these regional trade arrangements are shared widely across America.

The Global South represents over half of the world’s gross domestic product. Its reaction to Western sanctions on Russia for invading Ukraine and Israel’s US-backed actions in Gaza has ranged from ambivalence to thinly veiled sympathy for Vladimir Putin and Hamas. Without necessary and urgent economic engagement along the lines mentioned above, the Global South, left with China as its biggest economic and trading partner, may harbor greater resentment and skepticism to the American cause in a future US-China conflict. US security and prosperity—particularly of its middle classes—call for economic bridges, not fences, to the fast-growing world overseas. US interests are best served by forward deployment of both security and economic alliances.

Kaush Arha is president of the Free & Open Indo-Pacific Forum and a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue.

Further reading

Mon, Aug 21, 2023

The United States has a message for China: Yes, de-risking is possible

New Atlanticist By Gabriel Alvarado

De-risking seems to have struck a nerve in Beijing, even as high-level US officials make the case that the United States does not seek to decouple from China.

Thu, Aug 10, 2023

A new White House order is taking aim at investment in Chinese tech. How will it actually work?

New Atlanticist By Sarah Bauerle Danzman, Emily Weinstein

President Biden has signed an executive order restricting certain outbound investment in an effort to address national security threats that China may pose to the United States.

Tue, Jul 25, 2023

Is ‘friendshoring’ really working?

New Atlanticist By

The Biden administration has identified around 2,400 critical goods and materials that fall under its efforts to move supply chains out of China. Check out what the data reveal so far.

Image: United States President Joe Biden speaks during an event on Bidenomics at Prince George's Community College. The economy remains a vulnerability for Biden in polls despite positive economic data in recent months, as recent data on a manufacturing boom, job gains, strong gross domestic product growth and easing inflation fail to resonate with voters. Featuring: President Joe Biden Where: Largo, Maryland, United States When: 14 Sep 2023 Credit: Al Drago/POOL via CNP/startraksphoto.com