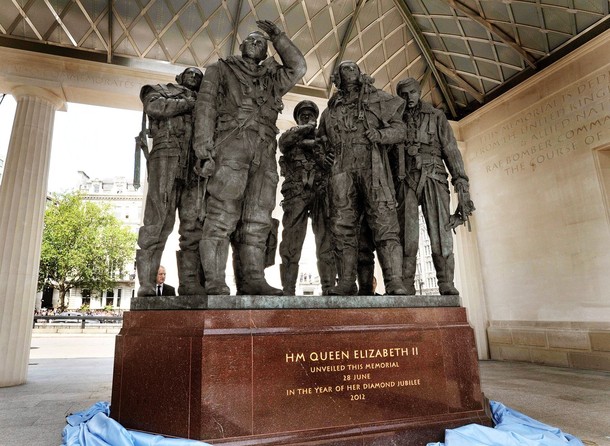

It is sixty-seven years too late. The Bomber Boys gaze over me looking exhaustedly and exhaustively for comrades who will never return. Seven RAF Bomber Command aircrew cast in bronze probably just off a Lancaster that has somehow miraculously survived a World War Two ‘trip’ over Nazi Germany.

Etched into the somber Portland stone of London’s beautiful new monument to the men of Bomber Command are Churchill’s famous words of September 1940, “The fighters are our salvation, but the bombers alone provide the means of our victory”.

RAF Bomber Command flew 364,514 sorties during ‘the war’. Of the 125,000 who clambered almost daily into Wellingtons, Halifaxes, Stirlings and, of course, the iconic Lancaster, 55,573 lost their lives. Only the German U-Boat crews suffered greater losses of any service in any force anywhere. Men had a 30% chance of surviving their first tour. As for the rest life was a lottery and they knew it.

Two weeks ago I had the honor to take breakfast in the mess at RAF Leeming sitting at a table where many young Britons and Canadians had eaten their final meal before being consumed by a fiery death over Germany. Last week Her Majesty the Queen unveiled this simple memorial to very brave men in front of thinning ranks of veterans from many nations as a lone Lancaster dropped a field of poppies over London’s Green Park.

For five years with growing accuracy and intensity RAF heavy bombers pulverised German cities and killed large numbers of German civilians night after terrifying night. One has only to visit a German city or read Max Hasting’s harrowing account of 5 Group’s 1944 attack on Darmstadt to get some understanding of the suffering that Bomber Command inflicted.

However, whilst I regret the suffering I have long-learned not to judge a past age by the values of the current age. This was total war that had to be fought and won totally against a regime that was seeking to subjugate Europe with its appalling mix of nationalism, racism and militarism. This was a regime that was sending millions to the gas chamber. In 1940-1941 Luftwaffe attacks on British cities such as Coventry, London, my own Sheffield and many others led to tragic loss of civilian life. Air Chief Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris made Britain’s position terrifyingly simple; “The Germans have sown the wind. They will now reap the whirlwind”. In August 1943 that whirlwind hit Hamburg which over two nights was virtually obliterated by the RAF. The damage was so great that Goebbels told Hitler that a few more raids like that and the war would be lost. Cologne, Kassel, Berlin and of course Dresden suffered raids of up to one thousand aircraft, as did much of the Ruhr industrial basin.

The debate over the strategic value and morality of the bomber offensive will continue on for many years to come, as will the debate over the value of Britain putting so much of its wartime industrial effort into producing large bombers. However, I will always recall the words of my Dutch wife’s great aunt who died two years ago at the age of 102. She told me that in the four years before D-Day the sound of the ever-increasing bomber streams passing overhead night after night to strike the Nazis hard gave real hope to the Dutch people that so long as Britain was fighting hard deliverance would one day come from brutal occupation as indeed it did.

Perhaps the greatest tribute we can offer these young men is not just this stunning memorial but the fact that Coventry and Dresden are today twinned in reconciliation. That atop the rebuilt Frauenkirche in Dresden sits a golden orb from Coventry. It also places today’s contentions in stark perspective. Whatever the tensions and irritations of the latest European crisis this is not a war; far from it. Britain and democratic Germany are today friends and it must always be thus. Indeed, even if Britain is forced to leave the EU, as I believe in time it will, we will leave as friends. L.P. Hartley’s famous reminder that the past is another country is nowhere as eloquent as Europe.

At the base of the memorial I found a note left by a relative. It commemorates New Zealand brothers John and George Mee who perished on sorties a few months apart. “As with their comrades they did not seek glory, they asked for no collateral for their lives, they demanded no privileges, no power or influence as they flew steadily into the valley of death”.

Julian Lindley-French is Eisenhower Professor of Defence Strategy at the Netherlands Defence Academy, Fellow of Respublica in London, Associate Fellow of the Austrian Institute for European and Security Studies and a member of the Strategic Advisory Group of the Atlantic Council. He is also a member of the Academic Advisory Board of the NATO Defence College in Rome. This essay first appeared on his personal blog, Lindley-French’s Blog Blast.

Image: bomber%20command_RAF.jpg