The Pakistani government recently announced a new budget aimed at guiding the country through the coronavirus pandemic and related economic crisis, as well as other longstanding domestic challenges in areas such as education and health care. While critics argue that the 2020-2021 budget released by Prime Minister Imran Khan’s administration will result in a greater deficit and allocates excessive funding to the defense sector, supporters have defended the budget and praised its introduction of the rationalization of custom duties as well as the advance ruling system, which would ease trade and minimize costs associated with cross border trade—a domain that Pakistan has historically struggled to contend in.

Here’s how Atlantic Council experts are assessing the budget:

The budget will likely struggle to reach key targets.

In its fiscal year 2020-2021 budget, Pakistan is targeting over 2 percent gross domestic product (GDP) growth, and a 7 percent fiscal deficit. Both of these numbers are considerably different than independent estimates of .2 percent GDP contraction and a 9.4 percent deficit. On the expenditure side, most of the items are projected to go down, albeit for debt servicing and defense. A combined 59 percent of Pakistan’s spending in this budget would be on external debt servicing (41 percent) and defense spending (18 percent, up 12 percent from the prior year) if prior year actuals are used as a benchmark; Pakistan will likely end up spending a higher amount on both of these key areas.

COVID-19 has added to Pakistan’s long list of basic health challenges. Around 40 million Pakistanis are undernourished or food insecure. As Pakistan grapples with this pandemic, its already stressed health infrastructure is unable to deal with the overflow of patients for both COVID-19 cases and otherwise. Even hospitals in big cities like Islamabad, Lahore, and Karachi are unable to cope with demand, which is likely to increase in the coming weeks. The current budget does not substantially account for this added public health burden.

On the revenue side, Pakistan is targeting a higher tax collection target, which is roughly 27 percent higher than the tax collection in the prior fiscal year. Given the ineffective tax net policies, tax collection, the havoc caused by the pandemic on Pakistan’s economy, and the effects of a large scale locust invasion on its crops (the agriculture and livestock sector accounts for about 35 million in Pakistan’s workforce), it is highly unlikely for Pakistan to meet any of these targets.

In fact, when Advisor to the Prime Minister on Finance Dr. Abdul Hafeez Shaikh was pressed for details, he offered the following; “The budget is an aspiration for reaching any certain stage that is based on a certain assumption. It is not like a holy book that cannot be changed. It is not budget of 19th century but it’s an evolving document that can be adjusted around the clock in line with ground realities.”

It is expected that Pakistan will likely introduce another mid-year budget later in this Fiscal Year.

— Sofyan Yusufi, senior advisor at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Pakistan’s budget is more aspirational than realistic.

Pakistan’s 2020-2021 budget estimates GDP growth will be 2.1 percent next fiscal year and predicts a budget deficit of 7 percent of GDP. Given that the Chinese economy—one of the world’s largest economies—will likely grow by less than 2 percent this year due to the COVID-19 shutdown and a slowing of global demand, Pakistan’s growth projections are clearly aspirational.

Pakistan’s budget seems to be made with an eye towards appeasing the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Skeptics would say that this sets Pakistan up for failure. While this may be true, these inflated numbers are likely the best Pakistan can publish as the country struggles to meet its IMF loan obligations, particularly in a post-COVID-19 era.

That said, while it’s important to have goals, those should be followed by serious reforms. Things Pakistan could do to kickstart its economy (and thus meet IMF targets) include broadening its tax base, attracting new foreign investment, and growing ongoing investment from multinational corporations. Further, the government should also focus on increasing tax revenue collection from its citizens, as opposed to a relatively small number of large businesses.

Finally, in a post-COVID-19 world, South Asian countries are actively trying to court manufacturing leaving China. While India is the most likely beneficiary of this trend, Pakistan should try to make itself an attractive climate for foreign investors by enacting structural reforms such as easing foreign direct investment (FDI) laws, fast-tracking regulatory reviews, and strengthening intellectual property (IPR) laws.

— Safiya Ghori-Ahmad, nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

The budget reflects problematic IMF policies in addition to internal shortcomings.

With the economy in a recession, the expectation was that the government, led by Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), would unveil a budget capable of rescuing the economy. Instead, a wholly unimaginative budget was tabled before parliament that has done little to inspire confidence. Aggressive revenue collection targets will most certainly not be met and the government is likely to borrow even more than anticipated, further crowding out private sector investment.

The one positive in the budget is the government’s move to rationalize tariff plans. This is a positive step, but it’s significance has been missed because of the budget’s other shortcomings.

But we must remember that along with the government, the IMF is at fault here as well. The targets have been set with an eye towards securing the IMF’s blessing, something that can only be gained by constraining government spending. This rigid commitment to austerity, at a time when Pakistan is facing its most serious socioeconomic crisis since independence, is going to inflict significant economic pain on Pakistanis in the coming months.

— Uzair Younus, nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

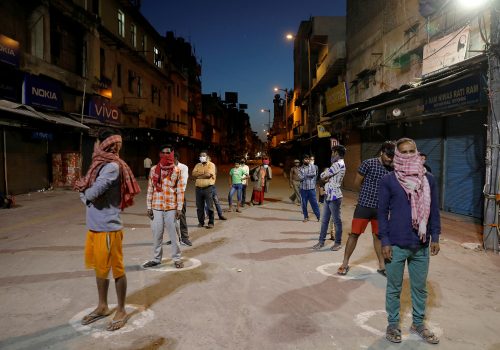

Image: A labourer wearing protective face mask fills air in a tyre at a workshop along a road, as the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Karachi, Pakistan, June 12, 2020. REUTERS/Akhtar Soomro