As the dust settles on three years of economic disasters, China’s leaders are grappling with a deep loss of public confidence that is affecting companies and consumers and casting a shadow over the country’s future growth trajectory. Even as Beijing claims a larger diplomatic and economic role on the world stage, Chinese businesses and foreign investors are becoming increasingly wary about the supposed strength of China’s economic foundations.

The damage from China’s policy mistakes extends across several sectors of the economy. Zero-COVID lockdowns decimated the retail, restaurant, and tourism industries. A regulatory crackdown clipped the wings of high-flying e-conglomerates and destroyed online education companies that once boasted over four hundred million users. A real-estate collapse set in motion by tighter control over property lending has undermined the balance sheets of developers, local governments, and households. Unemployment among young people in cities has been in double digits for months, and 11.5 million college graduates are poised to enter the job market later this year. Even foreign institutional investors, who only a few years ago were gung-ho on Chinese stocks and bonds, have cut back on their exposure to China’s financial markets partly due to their concerns about government policies.

With COVID-19 controls finally lifted, the Chinese economy is showing signs of an unsteady rebound after posting only 3 percent growth in 2022. But uncertainty about the direction that Chinese leader Xi Jinping and his newly announced leadership team will take raises doubts about the viability of Beijing’s aspirations for economic superpower status.

Of particular concern is the inability—or unwillingness—of China’s private sector to play a needed role in driving the country’s productivity growth, capital investment, technological innovation, and hiring. In its most recent assessment of the Chinese economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) singled out the “persistent weakness” of private investment and private consumption as a key reason that China’s economic growth “remains under pressure.”

When China’s National People’s Congress met earlier this month to seal Xi’s unchecked power over the country, the problems besetting the economy—not to mention any solutions—were left largely unspoken. But amid the triumphal declarations, there was an undertone of concern that hinted at the worries coursing through Chinese society, especially among the beleaguered private sector.

Xi himself seemed to reflect on this uncertainty at a meeting with business executives during the National People’s Congress when he called for the Chinese Communist Party to encourage the “healthy growth” of the private sector “so that they can let go of misgivings, be unburdened and develop with courage.” Newly appointed Premier Li Qiang followed a few days later at his inaugural press conference by saying “last year there were some inappropriate discussions about private entrepreneurs, which made them feel concerned.”

Chinese entrepreneurs have every reason to worry. Beijing’s harsh regulation of leading conglomerates over the past two-and-a-half years under a policy of constraining the “disorderly expansion of capital”—Xi’s catch-all criticism of what he saw as unchecked capitalism—has hit some of the country’s largest and most profitable companies. Businesses have cut back investment despite repeated assurances that what officials call “rectification” has been “basically completed” and regulators will pursue “normalized supervision.”

Among the government’s many actions against private companies, the initial public offering (IPO) of Alibaba Group’s Ant subsidiary was blocked in 2020, and Ant Group was subsequently restructured; the ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing was forced to delist from Wall Street in 2021 after proceeding with an IPO without Chinese regulators’ approval; and the online tutoring industry was hit with a ban on for-profit tutoring, leading to the wholesale destruction of companies. In addition, huge fines were levied against e-commerce conglomerates, after which many of the country’s most famous CEOs went into retirement or exile and over one trillion dollars of stock market capitalization were wiped out. The recent disappearance of one of China’s leading investment bankers—who was taken in to “assist” with a corruption investigation—has added to the uncertainty hanging over the business community.

Much of China’s crackdown on the private sector centered on activities that had been only lightly regulated in the past, such as practices now considered monopolistic; for example, major e-commerce company Alibaba was fined for preventing merchants from selling their products on competitors’ websites. Other business practices came under scrutiny and supervision as China’s political winds shifted. For example, data protection and cybersecurity—especially related to companies listing on Wall Street—became sensitive issues as tensions with the United States mounted. A multitude of new laws and regulations have been put in place, and approvals for new online products and services—especially video games—have languished in bureaucratic limbo. Moreover, the government’s acquisition of small stakes in several businesses—so-called “golden shares” that come with board seats—make it clear that control of the private sector will come from both without and within.

The end result for many companies has been sharply lower profits and plummeting stock market valuations. Mass layoffs have followed, with sixty thousand employees fired at one tutoring company and more than nineteen thousand let go at Alibaba, where 2022 revenue growth was the slowest on record. (On Tuesday, Alibaba announced a major reshuffle, splitting into six different business units.) That’s bad news for the coming wave of college graduates, most of whom won’t be equipped with the skills to find employment in “hard-tech” startups like semiconductor manufacturers and quantum computing firms that now are showered with subsidies and other support from Beijing. In February, the jobless rate among urban youth hit 18.1 percent, the highest level in six months.

Beijing’s campaign against such a vibrant part of the economy just adds to the scar tissue from the draconian zero-COVID policies that shut down cities and industries—and that were abandoned last year only after the unchecked spread of the Omicron variant and spontaneous street protests late last year that embarrassed the leadership. So it’s not surprising that as retail spending slowly recovers, Chinese consumers remain unsure about the future. It also doesn’t help that the property market remains in a deep downturn, affecting a sector that has contributed more than one-quarter of the country’s gross domestic product and directly hitting at least 70 percent of urban residents’ personal wealth.

Chinese leadership now offers soothing words to business, with Xi cooing at the National People’s Congress that “[w]e always regard private enterprises and private entrepreneurs as being in our ranks, giving them support when they are in difficulties and offering them guidance when they are uncertain about what to do.” But actions speak louder than words, and the “rectification” of the past few years represents one more self-inflicted economic wound. While the government’s program of supporting thousands of startups may one day bear fruit with new employment-generating high-tech enterprises, Beijing also has a track record of pouring capital into money-losing ventures plagued by corruption.

At a moment in which China faces mounting economic uncertainties—including looming recessions in important foreign markets—its most successful companies have been handcuffed by statist impulses. The end result could very well be slower growth and fewer opportunities for Chinese and foreign businesses—for example, a recent survey shows that one-half of US companies do not plan to make new investments in China. All this adds up to a bleaker outlook for continued improvement in the Chinese people’s standard of living. No wonder the celebration of Xi’s continued rule was largely confined to the halls of power.

Jeremy Mark is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Geoeconomics Center. He previously worked for the IMF and the Asian Wall Street Journal. Follow him on Twitter: @JedMark888.

Further reading

Sat, Mar 25, 2023

‘When we are together, we drive these changes.’ What Xi and Putin’s deepening alliance means for the world order.

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

At the three-day meeting this week in Moscow, the Russian president’s desperation met the Chinese leader’s opportunism. The visit marks an inflection point for global order.

Thu, Feb 23, 2023

United States–China semiconductor standoff: A supply chain under stress

Issue Brief By Jeremy Mark, Dexter Tiff Roberts

What are the implications of US semiconductor policy for global semiconductor supply chains and the competition for primacy in an industry critical to the economy and global security?

Tue, Feb 21, 2023

Offensive friendshoring and deteriorating US-China relations

Econographics By Hung Tran

The increasingly offensive use of an offensive US friendshoring policy will make it more challenging to manage US-China strategic competition

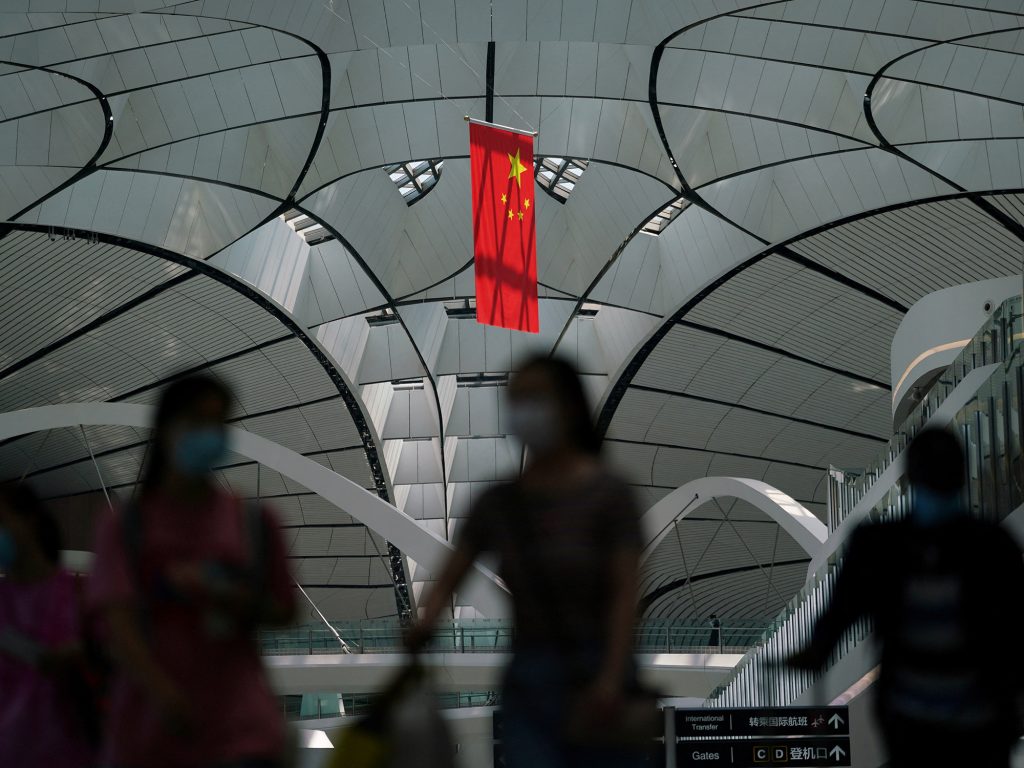

Image: People wearing face masks following the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak walk under a Chinese flag at Beijing Daxing International Airport in Beijing, China on July 24, 2020. Photo via REUTERS/Thomas Suen.