India’s non-performing loan (NPL) malaise, first uncovered under the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governorship of Raghuram Rajan, has underscored fundamental flaws in credit underwriting and risk management by a majority of banks in both the public and private sector. Aided by questionable ratings from some of the country’s top credit rating agencies and their own bullish perception of promoter creditworthiness, Indian banks have been stacking debt onto the balance sheet of overleveraged companies. Moreover, bank consortiums have wagered big bets on greenfield infrastructure projects, which require specialized and entirely different sanctioning criteria than most bank loans. A string of hefty defaults by top corporate names has clearly exposed regulators and investors to these apparent lacunae, resulting in the RBI resolutely toughening supervision and loan loss provisioning.

In tandem with this regulatory tightening, several larger banks have also made valiant efforts in the last few years to rid themselves of a lingering NPL problem. Resurgent Indian equity markets have seen investors reward private sector banks for cleaning up their balance sheets and focus on better rated assets. Against this backdrop, however, has come the recent collapse of the fifth largest private lender, Yes Bank, and the emergence of new NPLs caused by a slew of large non-bank financial institution and corporate debt failures. The alleged corruption linked to a couple of bank CEOs and several bigname borrowers has resurrected misgivings of the past and sent investors scurrying, compelling the RBI to look beyond the usual coterie of institutions to save Yes Bank from the brink and prevent a run on bank deposits.

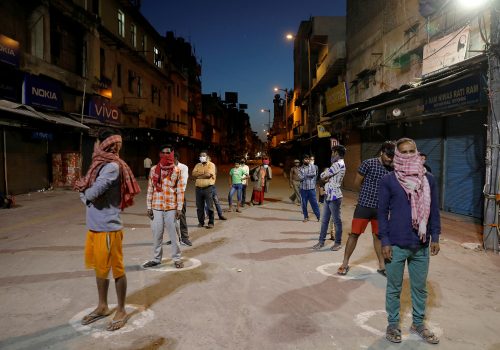

The unwelcome arrival of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the accompanying national lockdown is very likely to bring on a fresh wave of NPLs as banks resort to credit contraction to preserve capital for future losses. And this time around, it will not just be known corporations needing to restructure their obligations. In the absence of both revenue or income and working capital during the shutdown, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and retail borrowers, whose inclusion on the balance sheet of banks has grown exponentially, will end up forming the bulk of new bank NPLs.

The government and the RBI will have to take greater emergency measures to help banks counter the fresh onslaught of NPLs and to release credit back into the economy. The RBI took immediate and timely action at the end of March to boost liquidity by cutting repo and reverse repo rates in a bid to stimulate lending by banks. The regulator also allowed banks to provide a three-month moratorium on principal repayments to all borrowers. Both measures have proven to be short-lived as credit uptake by banks continues to show a downward trend with the halt in economic activity and interest obligations on debt repayments remaining a burden for cash-strapped borrowers.

In anticipation of an optimistic turnaround in 2021 and 2022, the RBI has taken an aggressive stance on monetary policy and introduced several liquidity-enhancing measures in mid-April. The liquidity coverage ratio for banks has been reduced from 100 percent to 80 percent, and a special refinance window has been created for MSME borrowers. Reverse repo rates have been cut further to discourage banks from parking idle funds with the RBI and deploy them instead in investments and loans. In an aim to free up capital, the RBI has also proposed a delay in loss recognition for defaults from thirty to ninety days along with a directive prohibiting dividend payouts by banks.

The RBI’s additional liquidity stimulus begs the question where all this money will be parked in an unpredictable economic climate. Knowing what investors will do to their stock if they take on excessive risk, several banks are very likely to pass over this surplus pool of funds. Others may have forgotten the lessons of the 2008 Financial Crisis and skew their behavior once again towards weaker asset growth, leading to another possible NPL upheaval down the road. If banks are indeed going to be efficient vehicles for transmitting this much needed liquidity, much of the risk needs to be defrayed by the government. Structured lines of credit where the first loss is absorbed by the government or a third party, like a multilateral institution, may have a better outcome for liquidity to reach targeted MSME, retail, and corporate borrowers.

Restricting dividends, while likely to be unpopular with shareholders, is a small but welcome step towards preserving capital. The change in asset classification for NPLs from thirty to ninety days, however, is only a temporary salve and will simply postpone the day of reckoning for banks to take on massive provisions that eat up scarce capital. What appears urgently needed is additional regulatory capital for banks to weather the NPL shock. With financial markets in a tailspin, the responsibility to fund new capital needs to be squarely borne by the government and/or the RBI. Otherwise, India’s banking sector will never fully recover from an NPL-induced coma.

Ketki Bhagwati is a senior advisor to the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

Image: FILE PHOTO: Police stand guard as depositors (unseen) of the Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank (PMC) attend a protest over the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) curbs on the bank, outside a RBI office in Mumbai, India, October 1, 2019. REUTERS/Prashant Waydande/File Photo