“This is an existential challenge.” In his long-awaited report on European competitiveness published on Monday, former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi issued a clarion call about the dangers of lagging growth and productivity in the European Union (EU). The lack of both, he explained, poses a direct threat to Europe’s ambitions, independence, and social model. “Never in the past has the scale of our countries appeared so small and inadequate relative to the size of the challenges,” he warned. Draghi’s solution? A continent-sized increase in investment of more than $880 billion per year. (As a share of gross domestic product, that’s more than double the investment during the Marshall Plan after World War II.)

Below, Atlantic Council experts answer five urgent questions about what’s in the report and what it means for the EU, the United States, and more.

1. Why the focus on competitiveness?

“Competitiveness” has entered the pantheon of EU-bubble speak for a catch-all term to describe Europe’s woes. It fundamentally describes a concern that Europe is being left behind. The bloc’s growth is outpaced by both the United States and China. For example, Europe pales in comparison to the United States when it comes to tech superstars. It also pays more for energy, struggles to attract investment, and merely regulates what others innovate.

The competitiveness fever is as much political as it is geopolitical. It was the primary focus of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s recent bid for a second term. Competitiveness would be her first priority, she promised, in her speech before the European parliament in July (and some of Draghi’s recommendations have already found their way into her political program for the next five years). This is certainly part of the effort of von der Leyen and her allies to distance themselves from the stereotypical image of the EU as a behemoth rulebook that makes doing business impossible.

But competitiveness is also a geopolitical concern. A Europe that cannot compete economically, cannot de-risk, and finds itself dangerously exposed to price shocks from energy suppliers or those on whom it will rely for the green transition, for example, will not be a factor on the world stage. A focus on Europe’s growth should be seen through that geopolitical lens as much as a purely economic or political one.

—James Batchik is an associate director at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

2. What does the report identify as the major cause of the EU’s lagging competitiveness?

European productivity and growth lags that of the United States and China. Also, Europe has few companies in the top echelons of the global technology industry, and relies too heavily on older, industrial companies for its research and innovation. Without growth and competitiveness, it will become increasingly hard for Europe to fund its social programs and ensure quality of life for its citizens. The report identifies three critical issues—innovation, climate, and security—where Europe is not leveraging its size and scale due to fragmentation and a lack of coordination.

—Penny Naas is a nonresident senior fellow with the Europe Center.

The report provides well- and lesser-known factors to explain the EU’s lagging competitiveness.

Despite the single market’s many achievements, persistent fragmentation in sectors like tech, finance, and defense mean that the EU is unable to compete with US and Chinese behemoths. This has created a vicious cycle between tech and finance, in which promising start-ups leave the EU for California as they seek larger investments and partnerships with larger tech firms. These ills have been diagnosed before.

Draghi’s focus on the lack of innovation is more original, and brings all of the aforementioned problems into a new light. He would like to see risk-takers better rewarded through government grants and private financing, which could be boosted if more EU member states switched from taxpayer-funded pensions to pension funds—a highly controversial proposal for some, such as France.

—Charles Lichfield is the deputy director and C. Boyden Gray senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

3. What is the report’s most significant recommendation?

Draghi deserves credit for not ducking the question of regulation. EU regulation is necessary to make the single market work, and while it is often applied worldwide by firms out of convenience, it is also employed as a guarantee that a good or a service meets an acceptable standard. The problem is that the exports of EU firms have derived little to no competitive advantage in hailing from the market that exported the regulation. The report calls for more responsive and parsimonious regulators, capable of anticipating where technology may go.

Much will be made of Draghi’s carefully-calibrated comments on common debt issuance. The report goes as far as it can to argue that this would be a useful component to get investment to the level it needs to be at (an extra $885 billion a year). But it stops short of saying this is mandatory. Doing this would have made the report an easier target for fiscal hawks, such as the German finance minister.

—Charles Lichfield

The most significant recommendations concern reforming European energy markets. The high price of energy makes Europe uncompetitive and threatens European industries, but inefficiencies in Europe’s energy markets could improve with some of the smart recommendations from this report. Eliminating some of the intermediaries would have an immediate impact on energy prices, bringing cheers from consumers, businesses, and governments.

—Penny Naas

4. What might this report mean for the EU’s approach to China and Russia?

The report includes a large section on building the EU’s security and resilience, and lessening Europe’s dependency on Russia and China for certain raw materials and other critical inputs. The report recognizes that the EU has been too dependent on other nations for certain critical inputs and outlines an entire strategy to lessen this dependence and diversify the EU’s trading partners. Moving forward, the EU will be more active in identifying potential vulnerabilities and using a series of tools to lower their risks.

—Penny Naas

5. Do the report’s recommendations put it at odds with the United States?

In this report, Europe has compared itself to the United States, which it sees as its nearest economic rival, but that should not put it at odds with the United States. The United States should encourage the EU to implement Draghi’s recommendations and improve its competitiveness, as the United States needs its allies to be independently strong and vibrant to confront growing international challenges. European nations will not be able to implement this bold agenda alone, and they will need partners who can help them execute their vision.

—Penny Naas

One striking aspect of the Draghi report on EU competitiveness is how much it compares and contrasts the EU with the United States. Taking this as an invitation to view the report through the lens of transatlantic trade relations, the report triggers a few observations.

First, the report frequently cites excessive and burdensome regulation as an obstacle to EU competitiveness. An important way to address this challenge is to adopt practices ensuring that all stakeholders, including in the United States, can provide meaningful input into EU regulations and directives that impact international trade and investment. This is a way of arriving at smarter regulations that both achieve their objectives and encourage the international trade and investment that is key to competitiveness.

Second, the report suggests an increased and more targeted use of tools to combat and protect against non-EU unfair trading practices that undermine EU competitiveness. The United States has similar challenges with respect to many of the same unfair practices in third countries. The effectiveness of EU tools would be greatly increased if the EU and the United States coordinate their (often different) tools to combat the same practices. Such enhanced cooperation would be an important step in ensuring future EU competitiveness.

Third, the report talks about the importance and competitive opportunities of decarbonization to combat climate change. Again, there are huge opportunities to work jointly with the United States on innovative ways to incentivize trade in low-carbon products (the sustainable steel and aluminum arrangement being just one example). A less favorable, but not less likely, approach is to work in isolation, with the potential for US-EU trade clashes. Much the same could be said about supply chain dependencies, protection of labor rights, and many other challenges to competitiveness that the EU and the United States have in common.

—Daniel Mullaney is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and GeoEconomics Center.

Further reading

Thu, Jul 18, 2024

What to expect from Ursula von der Leyen’s second term

New Atlanticist By James Batchik

The European Parliament has given European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen a second term, but it will be different from her first in several important ways.

Wed, Jun 12, 2024

Europe is gearing up to hit Chinese EVs with new tariffs. Here’s why.

New Atlanticist By

The European Commission just proposed new tariffs on China-made electric vehicles of up to 38 percent. Atlantic Council experts explain why—and what might happen next.

Sun, Apr 7, 2024

Ursula von der Leyen set Europe’s ‘de-risking’ in motion. What’s the status one year later?

New Atlanticist By Jörn Fleck, Josh Lipsky, David O. Shullman

The European Commission president presented a new economic vision for the European Union’s relationship with China in March 2023.

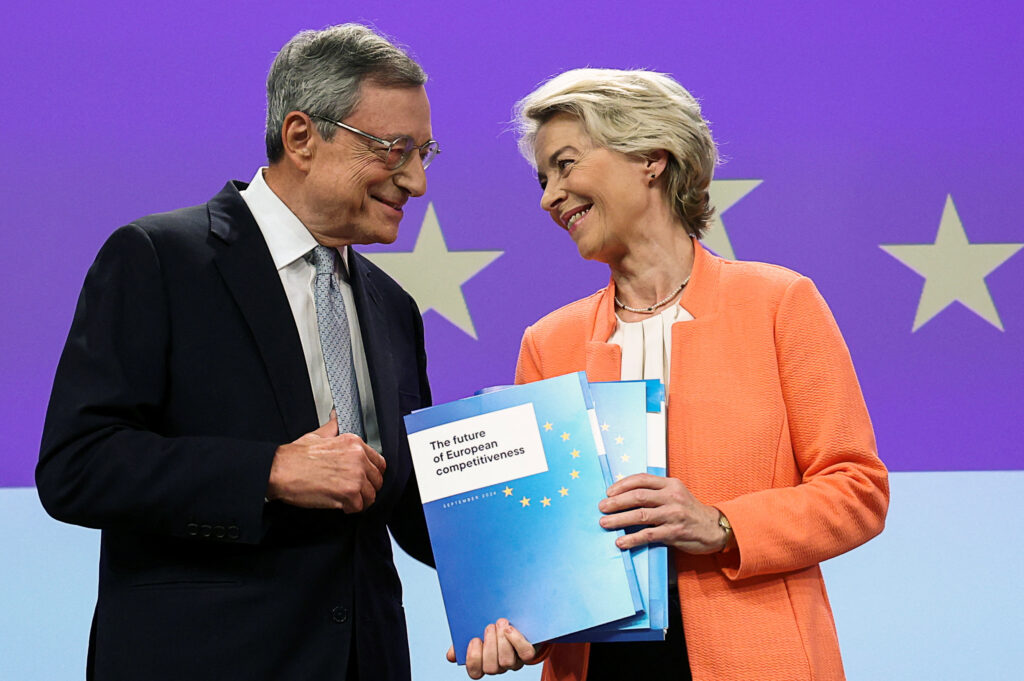

Image: European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen holds Former European Central Bank (ECB) chief Mario Draghi's report on EU competitiveness and recommendations, as they attend a press conference, in Brussels, Belgium September 9, 2024. REUTERS/Yves Herman