The rise of China and the US pivot to the Pacific has renewed the debate about American decline. One look at America’s university campuses will confirm that its soft power, at least, endures.

President Obama reignited this perennial discussion with his State of the Union address in January, declaring that, “From the coalitions we’ve built to secure nuclear materials, to the missions we’ve led against hunger and disease; from the blows we’ve dealt to our enemies, to the enduring power of our moral example, America is back. Anyone who tells you otherwise, anyone who tells you that America is in decline or that our influence has waned, doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

Political scientist Robert Lieber had made that case in detail in The Journal of Strategic Studies, pointing out that “America continues to possess significant advantages in critical sectors such as economic size, technology, competitiveness, demography, force size, power projection, technology, and in the societal capacity to innovate and adapt.”

Not everyone agrees.

Fareed Zakaria warned in Time last year that, “America’s success has made it sclerotic. We have sat on top of the world for almost a century, and our repeated economic, political and military victories have made us quite sure that we are destined to be No. 1 forever.” He fears this attitude will “ensure that the US. will not really face up to its challenges. We adjust to the crisis of the moment and move on, but the underlying cancer continues to grow, eating away at the system.”

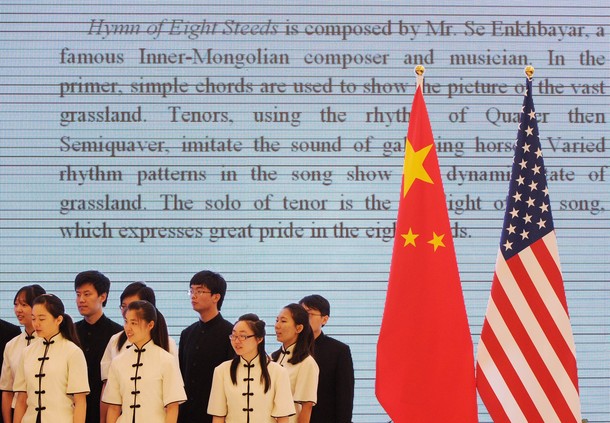

The other side of the decline debate is the rise of China. While the American pivot to the Pacific garners many headlines, China has been pivoting from Asia. As I wrote previously here,

Undoubtedly the rhetorical shift to Asia is linked to a frustration with long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, yet it is also driven by perceptions of China’s pivot from Asia. With few exceptions, China is often a top trading partner for many countries and the “Made in China” label is ubiquitous. Chinese-built stadiums and parliament buildings can be found throughout the Western Hemisphere and Africa. It is now possible to watch Chinese government sponsored English language news or study Mandarin at one of the hundreds of Confucius Institutes around the world. Chinese warships can be found in the Gulf of Aden protecting shipping from piracy and were off North Africa to evacuate Chinese citizens from Libya. China is attempting to contribute to global security through UN peacekeeping and working with countries the United States cannot such as North Korea.

The debate is far from academic as the rise of China and United States geopolitical position impacts countries’ international relations and individuals’ behaviors. Unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, there is little debate on college campuses where America’s enduring soft power is on display. The United States continues to garner students from around the world to study and to train.

As eyes turn to the Olympic Games in London next month, a surprising number of athletes will have trained in the United States. A recent Wall Street Journal headline captured the controversy-“Schools that Train the Enemy” citing the high percentage of foreign athletes on American college teams. Athletes come to take advantage of world class coaches, training facilities, and competition. The teams from top schools are increasingly composed of athletes who compete for other countries during the Olympics. At the Beijing Games, for example, athletes from US schools competing for other countries won 60 medals or six percent of the total. We should expect a similar result in London.

The significant number of students and athletes from other countries studying and training in the United States is a good indicator of the enduring soft power of the United States. When given a choice, individuals vote with their feet and see the United States as an attractive destination. This is true for Chinese elite who send their kids to the United States for college and athletes who compete for the rest of the world. This certainly causes some nationalist ire, but we have about two centuries worth of experience to suggest that when competition increases, Americans tend to innovate and thrive. As Robert Lieber concluded in his article, “the ultimate questions about America’s future are likely to be those of policy and will.” Policy to choose continued global engagement and the will to work through domestic challenges by drawing from the strength of its diverse population.

Derek S. Reveron, an Atlantic Council contributing editor, is a Professor of National Security Affairs and the EMC Informationist Chair at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Photo Credit: Getty Images

Image: us-china%20relations.jpg