European Union Heads of State and Government reached a crucial agreement in the early morning of July 21 to establish a massive fiscal recovery package to help the most affected countries recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and a multi-annual budget framework for 2021-2027. The €1.8 trillion agreement was the subject of intense debate over several days, but in the end European leaders reached a compromise that is a win-win for all sides and will strengthen the EU’s economy and political stability during turbulent times.

A welcome missing building block in the EU’s architecture

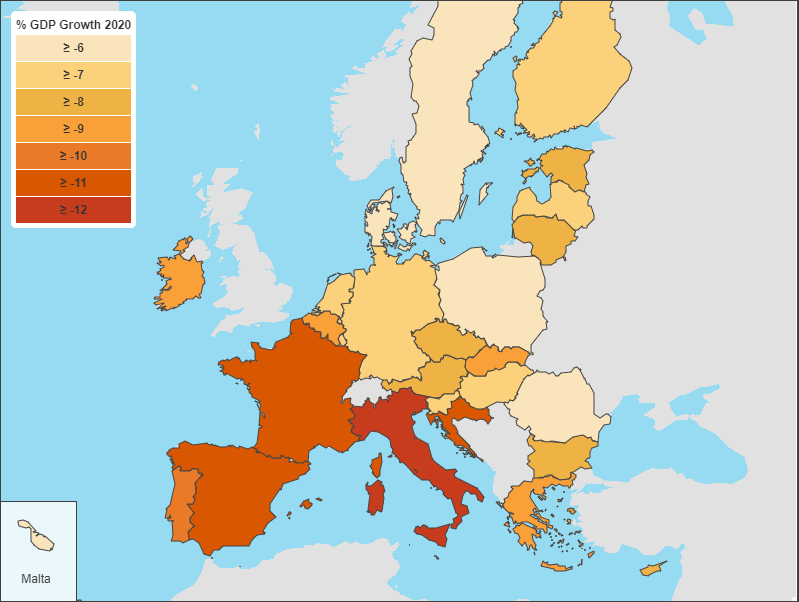

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdowns particularly impacted those EU countries that had been the hardest hit by the Great Recession and were left with high levels of public and corporate debt, and unemployment. The lockdowns particularly disrupted the leisure, hospitality, and mobility industries, which account for a large share of activity in Greece, Italy, Spain, France, and Croatia.

The €750 billion recovery plan will boost investment by roughly 1.35 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) annually over 2021-2024. It will be financed through borrowing on behalf of the EU, to be repaid over time until 2058 from appropriations within the EU budget.

The recovery plan is a one-off decision to respond to the pandemic, as an add on to the 2021-2027 budget plan. It will not consolidate members’ outstanding debt stocks and is not a “Hamiltonian gamechanger.” But it does mark a significant step and may be a pilot exercise towards giving the EU a tangible countercyclical mechanism, making the EU’s institutional architecture more resilient by allowing it to respond to economic downturns on its own.

Chart source: European Commission

Why has the German government changed its mind? Self-interest.

The recovery plan builds on a joint initiative by Germany and France that marked a turnaround in the former’s reluctant position towards financing distressed member countries. Germany and France recognize that the proposal is in their self- interest even more than out of solidarity.

Germany and the Netherlands, as most EU countries, send more than one half of their total exports to other EU countries. As global demand has weakened, keeping the rest of the EU afloat will mitigate the damage for the Northern European exporters. In response to the downturn, the richer Northern countries are mobilizing massive financial transfers and guarantees to support their own domestic firms. These steps have been accepted by EU authorities because of the exceptional circumstances, but these measures implicitly give companies in those countries an advantage over those in more indebted countries which cannot afford the same levels of support.

By funding green and digital investment projects, the EU recovery plan helps level the playing field. According to European Commission estimates, it will lift GDP growth in the weaker economies by 4.5% by 2024 and, through spillovers across the European economy, will add between 1.25% for the higher income countries and over 4 percent for lower income countries by 2024, more than offsetting their contribution to the reimbursement burden of the proposed program. It is therefore a win-win initiative for all involved.

Subscribe to The future is here: A guide to the post-COVID world

Sign up for a weekly roundup of top expert insights and international news about how coronavirus is reshaping international affairs.

Pressure at home spurs Frugal Four objections

The Dutch government, speaking for Austria, Denmark, and Sweden (the so-called “Frugal Four”) and also Finland, acknowledged the need for support and accepted one-off joint EU borrowing, on the condition that the recipient countries bear a large part, if not all, of the responsibility for repayment. They argued that countries should bear the recovery burden themselves and borrow under their own name given the current favorable financial conditions. Their inflexible position led to a slight reduction in the total size of the multiannual framework, and to a downward revision in the share of grants versus loans in the recovery program, from an initial €500-250 billion to a final €390-360 billion ratio.

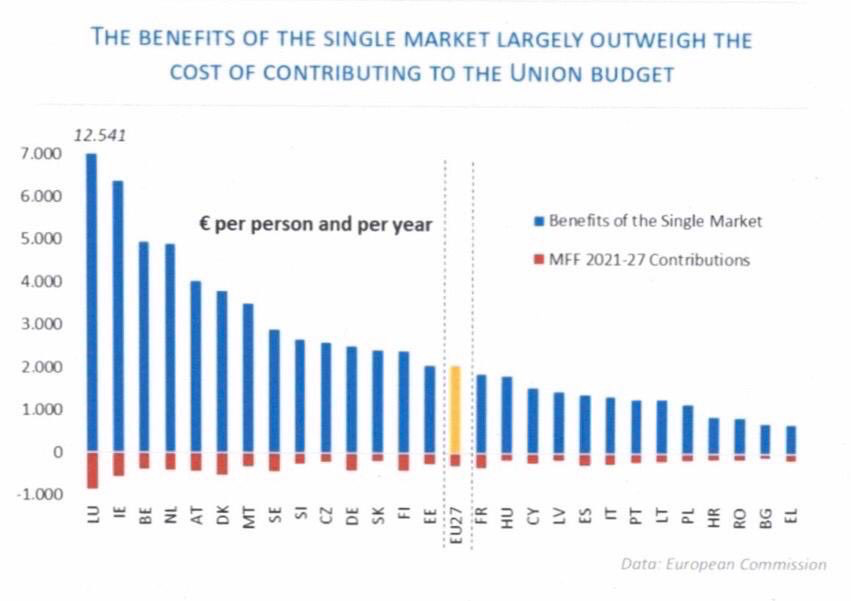

Moreover, Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany will continue to enjoy special rebates for their own financial contributions to the EU budget, on the grounds that their net transfers through the budget to other members are too onerous. Net transfers from these countries are typically of the order of 0.3-0.4 percent of their GDP, which pale in comparison with interstate transfers through the US federal budget, that can reach more than 7 percent of GDP for some US rich states. They are also tiny in comparison with these countries’ own budget sizes, which range between 42 and 54 percent of their GDP according to the European Statistical Office, and with the estimated benefits that they draw from the EU’s open internal market.

The group of five countries further contended that Southern members’ predicament is due to their procrastination in implementing necessary reforms. Hence, they fought for—and obtained—conditions that any EU disbursements to recipient countries would depend on reform plans and timetables approved and strictly monitored by the twenty-seven finance ministers.

Chart source: European Commission

The Dutch government’s adamant position can partly be explained by forthcoming elections and pressure from domestic political parties, who contend that their Southern neighbors’ difficulties are the result of their poor work and fiscal ethics, which is based on half-truths and myths. The five reluctant countries also wanted to ensure that this exercise did not prove too easy to pull off, lest it paves the way for a permanent transfer mechanism in the future, or a mutualization of current outstanding liabilities for heavily indebted countries.

On the other side, the Southern countries underlined that the pandemic was an exogenous shock that they could not have prevented themselves. They opposed the severe and intrusive conditionality attached to last decade’s bailout programs and the social scars they left, which citizens have fresh in their minds. A recent independent evaluation of the last Greek assistance package acknowledged that the program was necessary, but criticized that the severe social consequences were not sufficiently anticipated and prevented. With high current levels of unemployment, poverty, and social exclusion, the necessary reforms will have to be adequately drafted and sequenced to avoid playing in the hands of national populists, who could use them to argue that the EU is hostile to their countries.

More political economy. Internal economic statecraft.

The European Commission, supported by many countries, had proposed to include in the agreement the option to freeze EU budget disbursements to countries deviating from common democratic and rule-of-law values and principles. In view of a number of policy decisions in Hungary and Poland, the EU activated existing provisions in the treaties to put political pressure on deviant countries, but they are not proving effective.

Using the budget as a statecraft instrument is tempting but not without risks. Hungary and Poland countered by threatening to block any agreement on the recovery plan, which required unanimous agreement, if governance conditions were attached to disbursements. Moreover, while many may want to avoid taxpayers’ money ending up in the hands of illiberal governments, EU funds are primarily used to improve the economic conditions of people and communities, and depriving some EU citizens of financial support because their governments do not respect their political rights, could amount to inflicting a double punishment on them. Mixing values and money does not always serve values well.

Eventually no explicit political conditionality was included at this stage. The usual sound financial management checks will apply, and leaders will discuss possible further measures in the near future.

The leaders’ lengthy and intense negotiations led to a win-win outcome for their countries and for the EU’s economy and stability. This may not be the last hurdle, however. The agreements will now go through the European Parliament vetting process. There, the agreement is likely to meet with objections to what some groups see as insufficient ambition in funding the green, innovation, and resilience programs, and excessive weakness on the rule-of-law conditionality and financing rebates for some countries. Negotiations between national leaders and the European Parliament are therefore likely to go in the direction of strengthening what is already a bold fiscal agreement towards a more sustainable and resilient Europe.

Antonio de Lecea is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program, and associate professor of applied economics. He formerly served as minister for economic and financial affairs and principal advisor to the head of the delegation at the Delegation of the European Union in Washington, DC.

Further reading:

Image: Ireland's Taoiseach Micheal Martin, Netherlands' Prime Minister Mark Rutte and France's President Emmanuel Macron interact at the last roundtable discussion following a four-day European summit at the European Council in Brussels, Belgium, July 21, 2020. Stephanie Lecocq/Pool via REUTERS