As war and poverty fuel surge in migration, Europe debates immigration, integration, and identity

As the world faces its biggest migrant crisis since World War II, governments across Europe are struggling to find a solution to a situation that is as much about integration and identity as it is about immigration.

The European Union (EU) will hold an emergency meeting September 14 to discuss how to resettle 40,000 refugees that are already in Europe and 20,000 displaced persons who are currently in camps outside the continent. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker will propose increasing that number to 160,000 in his September 9 State of the Union speech.

Even if an agreement on resettlement is reached, the number in question is just a drop in the bucket, said Fran Burwell, Vice President and Director of the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Relations program.

“A solution for 60,000 people when Germany is expecting 800,000 asylum applications this year is a little short of what needs to be done,” she said.

A majority of the migrants arriving in Europe are from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan; most were funneled through Libya by a network of human traffickers. Now, alternate routes are also being used through Turkey and Europe’s east.

More than 300,000 people have risked their lives on perilous journeys across the Mediterranean Sea so far this year, in a desperate attempt to escape war, poverty, and hunger. Almost 200,000 have made it to Greece and 110,000 to Italy, according to UNHCR, the UN refugee agency. But about 2,500 others have not been that lucky. They have either died or gone missing, said UNHCR spokeswoman Melissa Fleming.

The severity of the humanitarian crisis has been brought into sharper focus over the past week after seventy-one migrants were found suffocated to death in the back of an abandoned truck in Austria, fifty migrants were found dead in the hold of a ship of the Libyan coast, and the body of a Syrian toddler washed ashore near the Turkish resort town of Bodrum.

Blocked by Hungary

Migrants moving through Europe have run into a formidable obstacle—Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In his quest for “Europe to keep belonging to the Europeans,” Orbán is building a 109-mile-long razor-wire fence along Hungary’s border with Serbia to deter migrants.

Will a fence keep out migrants driven by desperation?

“As governments raise obstacles, the smugglers will find even more inventive, and by definition dangerous, ways to smuggle people into Europe,” said Karim Mezran, Resident Senior Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Even as the Orbán administration has made it difficult for migrants to enter Hungary, it is also making it harder for those who have made it across the border to leave. The Hungarian government cites EU laws that restrict the movement of migrants once they have been formally processed.

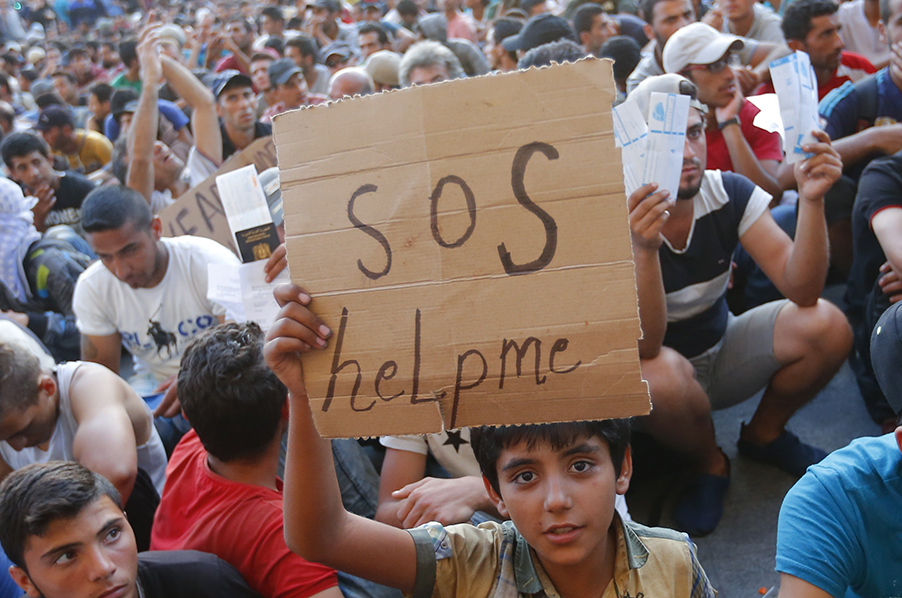

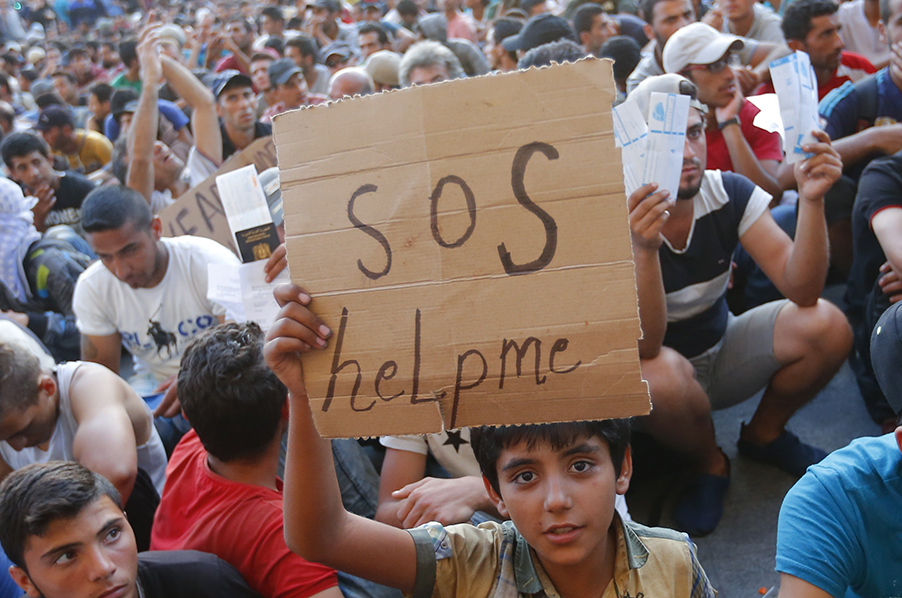

This week, about 2,000 migrants were involved in a tense standoff with riot police at Keleti railway station in eastern Budapest after they were prevented from boarding trains leaving Hungary.

Under an EU rule known as the Dublin Regulation, refugees should seek asylum in the first EU country that they enter. Frontline states such as Greece, Italy, and Hungary have been overwhelmed by the numbers, and are perhaps reluctant to register the migrants because that means assuming responsibility for them, said Burwell.

For many migrants, it is the stronger European economies that hold out better prospects of a job—Germany and the United Kingdom, for example—and not Greece or Italy, that are the desired destination.

Orbán cited this sentiment, along with German government’s pledges to view Syrians’ asylum applications favorably, which he views as encouraging migration, to declare September 3 the migrant crisis a “German problem.”

A German welcome

While the Hungarian response represents one end of the spectrum of how Europe is reacting to the migrants, at the other end are governments and citizens that have been more welcoming.

At the European Forum Alpbach conference in Austria in August, the Presidents of Austria, Croatia, and Slovenia urged Europe to welcome refugees with “dignity and decency,” said Nicholas Dungan, a Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Relations program.

“The attitude toward the migrants is not an attitude of Donald Trump—except perhaps for Viktor Orbán in Hungary. The attitude is one of compassion and humanitarian concern. However, the administrative response to that is different in different countries,” said Dungan, noting that there is no single European policy for dealing with the migrants. (Trump, a Republican presidential candidate, has vowed to build a wall along the US border with Mexico to keep out migrants.)

Germany has taken in more asylum seekers than any other European Union country. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has pledged to dedicate more money to helping migrants and urged other EU nations to do their bit.

Icelanders, meanwhile, want their government, which has said it will accept fifty migrants, to take in as many as 5,000. Members of a Facebook group even offered to throw open their homes to migrants, donate money and clothes, and help the new arrivals assimilate.

Tackling root causes

Britain, weary from its experience with Eastern European immigrants, has taken in just 216 Syrian migrants. [Update: British Prime Minister David Cameron said September 4 that Britain would take in “thousands” more Syrian refugees from camps outside Europe.] Cameron had earlier said taking in more refugees is not the answer. He believes the best solution is bringing peace and stability to the Middle East.

That’s easier said than done.

This spring, the European Union put in place a three-pronged response to the migrant crisis that included stabilizing countries from which the migrants are fleeing. (The other two prongs of the EU response are: strengthening maritime search-and-rescue operations and providing financial support to frontline European states.)

“This, obviously, is a policy with real limitations when you are talking about countries like Syria and Libya,” said Burwell.

Mezran said the fact that Syria and Libya are both failed states has deprived Western governments of a credible interlocutor with whom to discuss the situation.

“That Libya is a failed state is a bonanza for the human traffickers that now smuggle as many people as they can, unchecked, across a virtual highway that runs from central Africa through Libya to the Mediterranean coast,” Mezran said.

The crisis, meanwhile, has become “good business, not just for human traffickers, but also for NGOs and European armies that want bigger budgets to deal with this crisis,” he added.

While the majority of the migrants arriving in Europe are fleeing conflict, there are some who are trying to escape bleak economic prospects.

At the EU’s September 14 meeting, a list of “safe countries” is expected to be drawn up with the goal of repatriating economic migrants from these countries.

Fueling the Far Right

The wave of migrants and the debate over what to do with them risks fueling support for far-right political parties such as France’s Front National, Germany’s Alternative for Germany, the Freedom Party of Austria, and in Hungary Orbán’s Fidesz party.

Orbán himself has sought to whip up anti-immigrant sentiment with incendiary comments.

Claiming that most of the migrants are Muslims, he said: “Is it not worrying in itself that European Christianity is now barely able to keep Europe Christian? There is no alternative, and we have no option but to defend our borders.”

In August, neo-Nazis in Germany staged a violent anti-immigrant protest near a temporary shelter for refugees outside Dresden.

“As in most countries, there has always been an anti-immigrant element in European politics. Parties such as the Front National in France and Fidesz in Hungary have been using this significant increase in migration to bolster their own political standing,” said Burwell.

“We are at a point where even the very normal middle-class European society is concerned by the pictures that they are seeing every night on television of immigrants arriving on the shores of Europe, and not knowing how they are going to cope with this and how long it is going to go on,” she said. “That is very worrying in terms of its consequences for European politics.”

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: A migrant child holds a placard outside the railway station in Budapest, Hungary, September 2. Hundreds of migrants protested in front of Budapest's Keleti railway station demanding to be let onto trains bound for Germany. (Reuters/Laszlo Balogh)