This is the first in a series of explainers about the interconnectedness of criminal markets in Latin America and the Caribbean, written by the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. To get notified about future editions and other related work on the region, sign up here.

In Latin America, transnational criminal organizations, such as drug cartels, have evolved.

Backed by networks of economic activity, these groups have grown from local and regional gangs to multinational empires. Today, criminal organizations have economic and security resources that rival what some nations have—but without the same constraints and limitations. Thus, any policy intended to improve the Western Hemisphere’s security must include measures that target the increasing economic power of criminal organizations.

But where exactly is this economic power coming from—and how can countries interfere? Here’s a breakdown of the numbers that show the reach, power, and influence of these criminal organizations, with a focus on Colombia, seeing as the growth of these criminal organizations there serves as a warning to other countries in the region.

Colombia’s coca economy offers criminal groups one major source of profit and economic power. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimated that cocaine can fetch $69,000 per kilogram at wholesale prices in the United States, meaning that Colombia’s production capacity could rake in $183 billion. Colombia’s cocaine production exceeds 70 percent of the world’s overall production; if Colombia’s illicit cocaine industry were a country, it would be ranked fifty-seventh by gross domestic product, placed just below Ukraine. Cocaine supply routes are too well-resourced for Colombian authorities to stop the movement of cocaine from the country. Enforcement agencies are reporting increases in the seizure of cocaine, which helps them appear more effective; however, the overall increase in cocaine production has helped transnational criminal organizations avoid significant impacts from these seizures.

Illegal gold mining in Colombia also offers criminal groups the financing they need. In Colombia, there was a nearly twelve metric ton disparity between legally mined gold and gold exports in 2024. Based on an estimated price of $2,389 per ounce last year, this amounts to a $918 million disparity. And this criminal market is not isolated from its legal counterpart; it actually benefits from the systems set up by legal gold trade, as illegal mining operators sell via legal exporters, disguising the source’s origin with false documentation. These activities can have much more than just security consequences: They also can have environmental ramifications, for example, if such illegal mining poisons water sources. That poses an additional cost for the government and surrounding communities to bear.

Criminal organizations, with their rising economic power and influence, are growing more appealing to Colombian youth, who are especially vulnerable to recruitment. Weakening societal structures, limited economic opportunities, and the pervasive presence of criminal organizations enable this recruitment. According to a study by the United Nations Children’s Fund and the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare, several trends were common among recruits to transnational criminal organizations:

- 78 percent of minors experienced familial violence.

- 56 percent of minors had a family member in an “armed group.”

- 69 percent of minors came from low-income and rural families.

- 89 percent of minors were from regions where armed conflict was already prevalent.

- Recruited youth were on average thirteen to fourteen years old.

- Most recruitment takes place through incentives, and over 80 percent chose to work for the organization.

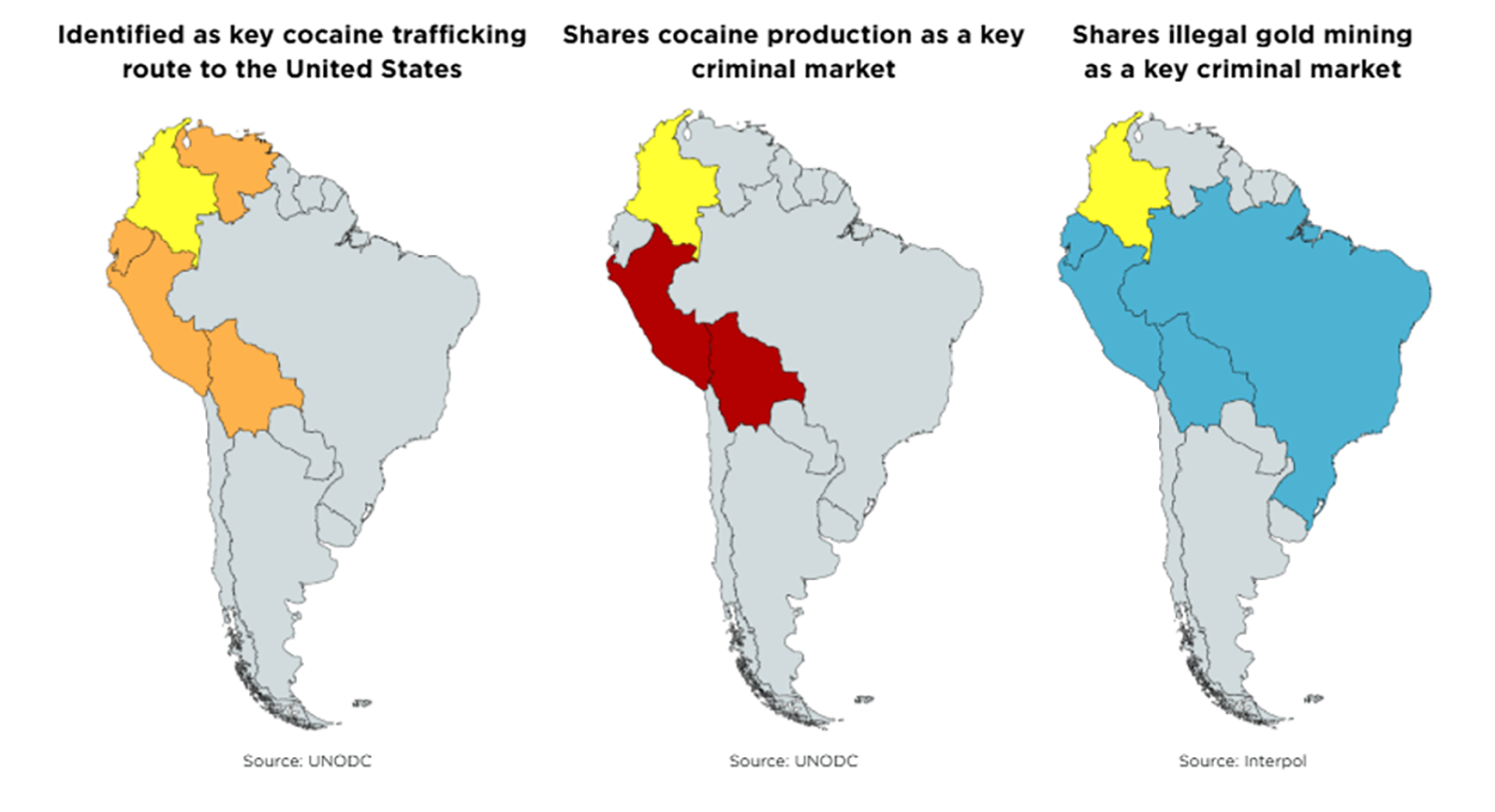

Criminal markets do not respect national borders

Due to the structure of transnational criminal organizations, when a single government increases its focus on countering a criminal market, the organizations shift toward countries with more permissive governments. These maps show the countries that share criminal markets with Colombia. Colombia’s efforts to restrict these criminal markets may lead to an osmosis of criminal activity across borders—if the countries that are part of the criminal market do not pursue a unified approach. This means that if one country sees a decline in illicit trade, its neighbors will likely experience an uptick. But as countries relax policies following a reduction in criminal activity within their own borders, the movement of criminal organizations can become cyclical.

Most US aid to Colombia has been designed to support security and counternarcotics. Even development assistance and economic support funds, which can be used in a variety of ways, are intended to help the Colombian government improve economic mobility and expand opportunities for Colombians—that is a necessary element in countering recruitment pressures. However, recent reductions in US aid could erode the Colombian government’s ability to directly counter criminal organizations and their recruiting practices.

Still, by working more closely with regional partners and by taking a holistic approach—simultaneously targeting the criminal organizations’ resources, their recruitment pipelines, and the criminal markets that empower them—Colombia can achieve at least some successes in countering criminal organizations.

Isabel Chiriboga is an assistant director at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Aaron Kolleda is a major for the US Army and is currently a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

The views in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the position of the US Department of Defense or the US Department of the Army.

Further reading

Wed, Jul 23, 2025

A terrorist designation should only be the start in weakening Mexican cartels

New Atlanticist By

The Trump administration’s designation of several Mexican drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations must be followed by actions that meaningfully weaken those groups.

Thu, Jul 17, 2025

The numbers that define the US-Brazil trade partnership

New Atlanticist By Valentina Sader, Ignacio Albe

The US president has threatened to impose a 50 percent tariff on Brazil in August. Before then, take a deep data dive into the current bilateral trade relationship.

Wed, Jul 16, 2025

Dispatch from Panama City: What’s behind the new optimism in US-Panama relations?

New Atlanticist By María Fernanda Bozmoski

A recent visit to the Central American country revealed that while the excitement there is palpable, so is the pressure to deliver.

Image: The Colombian Navy, the Colombian Air Force and the Joint Interagency Task Force of the United States Southern Command (JIATFS) seized more than 3.3 tons of hydrochloride cocaine in Santa Marta, Colombia on March 26, 2024. Photo by ULAN/Pool/Latin America News Agency via Reuters Connect.