Five Washington-based foreign ambassadors shared the stage with US officials June 29 to discuss the 2015 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR)—a report that deals with complex issues such as the rise of non-state actors.

Five Washington-based foreign ambassadors shared the stage with US officials June 29 to discuss the 2015 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR)—a report that deals with complex issues such as the rise of non-state actors.

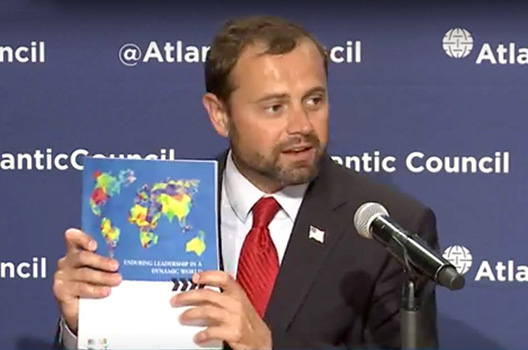

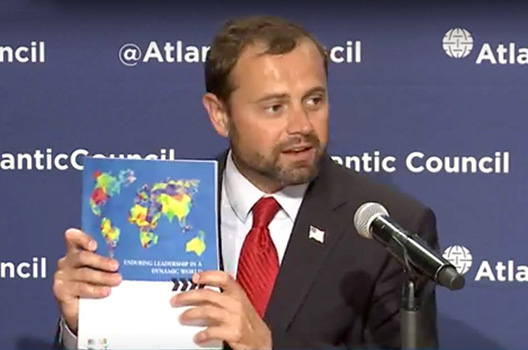

Thomas Perriello, QDDR Special Representative since his February 2014 appointment by Secretary of State John Kerry, unveiled the study at an event moderated by Barry Pavel, Director of the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scrowcroft Center on International Security.

Perriello said this year’s report, released in April, is 40 percent shorter and far more focused than the original QDDR, completed in late 2010 under the direction of his predecessor, Anne-Marie Slaughter. It targets four broad US objectives: defeating violent extremism, fostering open and democratic societies, developing inclusive economic growth, and countering climate change.

“In seeking to turn the tide of violent extremism, traditional nation-state structures are clearly no longer sufficient,” he said. “States are no longer the world’s only global influencers. In some cases, non-state actors like ISIS [Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham] supersede states. Organized crime accounts for 15 percent of global GDP. Critical tools of statecraft must be reinvigorated to deal with these changing trends.”

Perriello, a former Democratic lawmaker who represented Virginia’s Fifth District in the House of Representatives, said the first report was initiated by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton upon assuming office.

“She had served on the [Senate] Armed Services Committee,” he explained, “and felt it was important that our defense side take a time-out every four years and ask, ‘is this the way we should be doing things, or is this the way we’ve always done things?'”

Perriello said that from the outset, the QDDR’s function has been to “look at threats and opportunities, and make sure our budget, management structure and operations reflect a pro-active reading of the world—not just a re-active reading to where we were last year.”

Among other things, the study analyzes how US diplomats can best function in an era of diffuse and networked power.

“Where we see that diffusion is beyond a broader range of states than were traditionally able to get together and determine the outcome of world events,” he said. “Cities and megacities are increasingly taking on issues that used to be exclusive to the nation-state: immigration, trade, environment and sustainability, crime and terrorism issues.”

It’s not just a theoretical debate, said Perriello.

“If we believe in the importance of non-state actors, there has to be something we train our personnel to do,” he explained. “So we’re looking at more flexibility for personnel to spend a tour in the private sector, or in the NGO sector or in the tech community.”

But in many ways, the world hasn’t changed all that much, said Ashok Kumar Mirpuri, Singapore’s Ambassador to the United States.

“If I had to map out the time our foreign minister spends on non-state actors, it would be less than five or ten percent,” said Mirpuri. “In Southeast Asia, we recognize very clearly that the role of the United States is critical. It has guaranteed peace and security in the Asia-Pacific region since the end of the Second World War.”

He added that the twelve-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership now being negotiated is an agreement among countries, not non-state actors.

“When you deal with things like countering violent extremism, you turn back to states,” Mirpuri said. “The US knows how to deal with data. I don’t think any other country has a chief data scientist to help deal with issues like this. In Southeast Asia, we’re many, many miles behind what we could potentially do with this information.”

Paula Dobriansky is a Senior Fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center and a former foreign-policy advisor to five US administrations.

“I have to agree with Singapore’s Ambassador that the nation-state still is very important, but over the last several decades, we’ve seen the rise of non-state actors—not just those in the extremist category but also NGOs, public-private partnerships and businesses based abroad,” she said. “How those businesses conduct themselves can be a reflection of the values attached to a particular country.”

Dobriansky also noted the rise of coalitions—groups of countries formed to confront everything from avian influenza to ISIS. “These coalitions don’t have executive secretariats, but they come together in a flexible way based on a particular cause, and a belief that by coming together, they can deal with a situation more effectively.”

Ambassador Petr Gandalovic, who represents the Czech Republic in Washington, warned that with the rise of Twitter, Facebook and other social media, countries as well as non-state actors can wage online propaganda wars with ease.

“The nation-state is still a cornerstone of diplomatic relations. But at the same time, when this certain nation-state happens to be a democracy with open Internet and free media, it’s subject to all sorts of undermining actions of the other side,” he said. “In a very effective way the other nation can influence your public with messages beyond your control.”

Lukman Faily, Iraq’s Ambassador to the United States, said that’s an urgent issue in his part of the world.

“Do nonstate actors such as ISIS complement the state, or do they want to demolish the state?” he mused. “We have an immediate issue here. Twitter and FB are also used by ISIS specifically to wage war rather than as normal tools of communication. That has an immediate psychological impact. We need to know how agile the US and others are in dealing with such a problem.”

Faily added: “Time is also a crucial factor, and if the throughput of destruction is faster than the throughput of development, then we’ll have a real challenge here.”

Also participating in the debate were Ambassadors Juan Gabriel Valdés of Chile and Rachad Bouhlal of Morocco.

Larry Luxner is an editor at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Thomas Perriello, Special Representative for the Quadriennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) at the State Department, holds up a copy of the 2015 QDDR, titled “Enduring Leadership in a Dynamic World.” Perriello was one of half a dozen panelists at a June 29 diplomatic conference sponsored by the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security. Photo: Larry Luxner