In the summer of 2016, I was in Gaza City working with the health portion of Gaza2020, an ambitious US Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded project that aimed to improve the livelihood of Gazans. With twenty-one stakeholders represented, ranging from government ministries to major hospitals to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), my job was to facilitate an emergency and a non-emergency healthcare framework from 2016-2020.

Even in the best of times, Gaza, which has been under an Israeli-Egyptian siege for almost fourteen years, has a barely adequate health system for its population of 1.9 million, half of whom live under the poverty line and more than 30 percent of whom live in official refugee camps. In the emergency health framework, our objective was to ensure that procedures and supplies are sufficient enough to sustain patients while they wait for permits to leave Gaza for medical treatment and/or until medical aide from international donors arrive.

What was defined as “emergency” was heavily dictated by the horrors of the 2014 war with Israel. Hamas, a group the US State Department designates as a terrorist organization, used hospitals, ambulances, and other medical facilities as shields for its militants and weapon caches. In return, Israel used its air power to specifically target seventeen hospitals, fifty-six primary care facilities, and forty-five ambulances. The damage to the Gazan healthcare system was estimated at $50 million, not to mention the scores of civilians who became collateral damage. The bulk of our planning, therefore, focused on a communication system that could be shared with all sides to make sure that medical facilities were not targeted in the next wave of violence. The number of ventilators, intensive unit beds, and other essential medical equipment were formulated based on potential outbreaks of communicable diseases, such as cholera and measles, in addition to dealing with the increasing number of those diagnosed with diabetes and heart-related diseases.

We did not even consider a pandemic, much less an infectious and lethal one such as COVID-19. Under normal circumstances, Gazan healthcare is poor. Under COVID-19, to say that Gaza is struggling is an understatement.

Economic and security concerns

Gaza currently has nineteen confirmed COVID-19 cases, with hundreds more under quarantine. The numbers are suspected to be much higher—the Ministry of Health ran out of testing kits and is now relying on the WHO and the five testing kits recently donated by Israel. With little access to essential medical aid, Gaza is trying to prepare for the pandemic with eighty-seven ventilators—a large number of which are decrepit or semi-functional—homemade sanitizer, forty intensive unit beds, and two makeshift quarantine facilities in a school and a hotel. That is nowhere near the current demand or the projected numbers, according to the WHO.

Given Gaza’s isolation and the fact that almost two million people are cramped into such a small space—Gaza is one of the most densely populated areas on Earth—physical distancing, especially within refugee camps, is literally impossible. Though there has been a lot of forced ingenuity from Gazans—adapting existing materials to make sanitizers, facial masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE)—it is far from enough.

To exacerbate the situation, the economy, already suffering from the siege, has taken a further dive. Agriculture, the biggest sector, has plummeted, even with the relief checks handed out by Hamas. Bazaars, where produce has been traditionally sold, have closed, and prices of goods such as onions have fallen by half in the past two weeks. Restaurants and services have also closed, adding to the 80 percent of the population that already relied on international aid before the pandemic. 130,000 people have already applied for the 10,000 financial aid slots available for a one-time payment of $100/worker from the Ministry of Labor.

Israel, led by the United States, needs to lift some parts of the siege and allow more medical supplies into Gaza. If humanitarian concerns or the requirements of the Fourth Article of the Geneva Convention are not enough to motivate action, then the potential security consequences should. An inability to provide for one’s families and lack of dignity are directly correlated to security instability. Indeed, the need to raise the economic livelihoods of Gazans in order to ensure the prosperous survival of Israel was highlighted in the White House’s Middle East Peace Plan. With bleak future prospects of no jobs and the continuation of the siege, many of Gaza’s large youth population may see little to lose from defying quarantine measures and rioting, especially as they feel more protected from the virus’ danger due to their age.

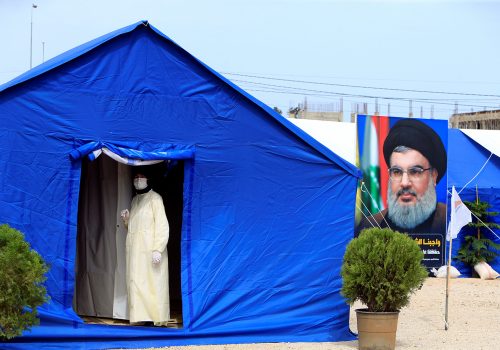

Finally, it is imperative to step in for the simple reason of realpolitik: the United States and Israel cannot afford to make Hamas look like a legitimate partner to other international actors and as competent government in Gaza. The movement has already won international aid from Qatar, who promised another $150 million in relief for Palestinians. Hamas is currently in talks with Turkey for its help after Ankara made a half of million dollar donation to Palestinians in Lebanon. Even China, which has minimal presence in Gaza, has donated a laboratory in partnership with Israel to allow for the processing of up to 3,000 samples a day. The more foreign aid Hamas can muster, the more credibility it gains to maintain its stranglehold over Gaza. That is disastrous for ordinary Gazans and Israel alike.

Eight US Senators, including Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), have called for more immediate aid to the Palestinians in both West Bank and Gaza, and the US Congress recently allocated $5 million for COVID-19 response to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank. That is a step in the right direction, but it is far from enough. Israel’s cooperation is needed to allow essential medical supplies into Gaza. The lowest hanging fruit for the United States is to reinstitute its yearly financial support for UNRWA, which is already on the ground and has the local know-how, and accelerate the allocation of $200 million in Palestinian aid in FY2020 budget for immediate use.

In January, 2020, I received a note from my Gazan counterpart that the emergency framework has been implemented. With COVID-19, I am frightened. I know that the framework cannot cope with the pandemic. It is only with the help of the Israelis and the United States that Gazans have a chance. And if it is not for humanitarian reasons, it is to prevent the next Intifada or the Great March of Return.

Evanna Hu is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading:

Image: Palestinians, wearing masks as a preventive measure against the coronavirus disease, work in a bakery in Gaza City March 22, 2020. REUTERS/Mohammed Salem/File Photo