As they’ve spread across the nation and around the world, protests over George Floyd’s death have focused on police brutality and criminal injustice. But it’s important to not lose sight of the concerns they’ve also raised about the economic injustice and inequity that COVID-19 has magnified and exacerbated.

While the White House cheered the surprising jobs numbers on June 5, many Americans—especially people of color, women, lower-skilled workers, young people, or rural residents—remain out of work and left behind by this nascent recovery. Black, Asian, and Hispanic unemployment were all higher than the national average with Black and Asian levels actually ticking up from last month—to 16.8 and 15.0% respectively—while the rate for Hispanics, 17.6%, was the highest of any racial or ethnic group. At the same time, youth ages twenty to twenty-four remain nearly two times more likely (23.3%) to be unemployed than the general rate; and unemployment among women over the age of twenty is currently 2.3% above that for men.

Black Americans nationwide are also significantly more likely to contract the coronavirus and experience both health and subsequent economic impacts. Overall COVID-19 mortality rate for Black Americans is 2.5 times as high as the rate for Asians, 2.3 times as high as the rate for Whites, and 2.2 times the Latino rate. In a number of states, the imbalance is far more dramatic: in the District of Columbia mortality among Blacks is six times higher than for whites, in Kansas and Wisconsin five times, and in Michigan and Missouri four times.

Importantly however, these individuals were in many ways already excluded from the dynamic growth that characterized the months—and years—preceding this latest crisis, magnifying systemic racial, ethnic, gender, and geographic injustice and inequity. The Economic Policy Institute studied wages and inequality over the past two decades and found constant and—and in some cases worsening—wage gaps by gender and race. The black–white gap was significantly larger in 2019 (14.9%) than it was in 2000 (10.2%).

At the same time, official government data in the most recent Condition of Education Report 2020 show that employment and economic inequality may, at least in part, be attributed to inequities in education. Earnings and employment levels among twenty-five to thirty-four year-olds are correlated with education levels. For example, in 2018 the median earnings of those with a master’s or higher degree ($65,000) were 19 percent higher than the earnings of those with a bachelor’s degree ($54,700), and the median earnings of those with a bachelor’s degree were 57 percent higher than the earnings of high school completers ($34,900). And, as it relates to COVID-19, lower skill workers were more likely to lose their jobs or see their hours cut.

Blacks, Hispanics, and Native people are all less likely than Whites to enroll in college, while Asian Americans are more likely to. High school dropout rates (sixteen to twenty-four year-olds) for Hispanics is nearly double that for Whites (8.0% versus 4.2%), while Blacks are 50 percent more likely to drop out (6.4%), and Native youth have the highest rates of noncompletion (9.5%). Moreover, Black youth age eighteen to twenty-four are nearly twice as likely to be “NEET”—not in education, employment, or training—than their white peers: twenty-one versus eleven percent (Hispanics rate is 15.5%).

Yet, statistics can only tell us so much and frequently mask other important underlying dynamics at play. For example, below these somber figures lies the inequality of education and labor market outcomes stemming from disparity of education quality—where lower income neighborhoods schools tend to be under-resourced, putting poorer students (often of color or in rural communities) at a disadvantage that could affect lifetime earnings.

Other indicators of economic opportunity also reveal inequality. Small business are the beating heart of the US economy, yet it is more difficult for women and racial minorities to obtain and pump blood—financing—into their enterprise bodies. Data from the Federal Reserve Small Business Credit Survey exposes minority and gender lending gaps. Black and Hispanic applicants were 15 percent less likely to be approved for financing than White or Asian applicants. Similarly, creditworthy Black-owned firms face ongoing challenges—relative to similar White-owned firms in terms of profitability, credit risk, and other factors, Black-owned businesses that applied for financing were 20 percent and 17 percent less likely to do so at large and small banks respectively. Other data shows women applicants were also 7 percent less likely than men to be approved. Entrepreneurs in low income communities also face challenges, including financial services with fewer banks for lending. In 2018, lower income zip codes averaged two bank branches while middle income areas averaged 2.7, and high-income zip codes having four branches.

Non-financial, education, or employment markers of opportunity further reinforce the economic disparity in America along racial, ethnic, and gender lines. In February, LinkedIn released its first “Opportunity Index,” based on opinion surveys and platform data to identify and measure priorities, aspirations, and the barriers to achieve these goals. Interestingly, in the United States, ‘the network gap’ plays a key factor in getting ahead. For example, more than 70 percent of professionals get hired at companies where they already have a connection. For lower-income Americans, however, building a strong network is likely to be an uphill climb as the study found those who grew up in a high-income neighborhood (one with a median income over $100,000) are nearly three times more likely to have a strong network that helps them get the job they want.

Taking social and economic markers into account, it all adds up to a widespread, generational, education, income, and opportunity inequality that is now magnified by the pandemic. On some level, the mechanisms to begin narrowing these gaps—such as increasing funding and resources for poorer school districts to improve infrastructure, technology, or teacher training; expanding accessibly free broadband; increasing grants or debt-free university offerings; or increasing low-interest lending to minority-owned business or mortgage applicants—may seem obvious, but are likely to be more difficult to achieve due to political, financial, social, information, or other obstacles.

The private sector and civil society may offer more innovative, data-driven, and effective solutions. Mentoring can help individuals see what’s possible and expand choices, grow their professional networks, build interpersonal or employment or business skills, add to their technical competencies, or access new markets, clients, or customers. Fintech, online, or algorithmic lending, for example, which may reduce bias (conscious or otherwise) show promise for women or minority entrepreneurs. Similarly, revising job postings, “blind” resume reviews that minimize demographic data of the applicant, and standardizing interviews, are among emerging practices that can reduce bias in the hiring process, and companies are increasingly taking other actions to improve diversity and inclusion and encourage or even incentivize employees to as well.

The United States is at an inflection point that will require a combination of policy, prioritized investing, and evidence-based practices by the public and private sectors to reduce the inequity and economic injustices that characterize communities across America and instead create intergenerational, interracial, and intergender opportunity and a more inclusive, progressive, and prosperous future. What is not clear is if we will seize this moment and do so.

Nicole Goldin is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program and managing principal of NRG Advisory. Follow her on Twitter @NicoleGoldin.

Further reading:

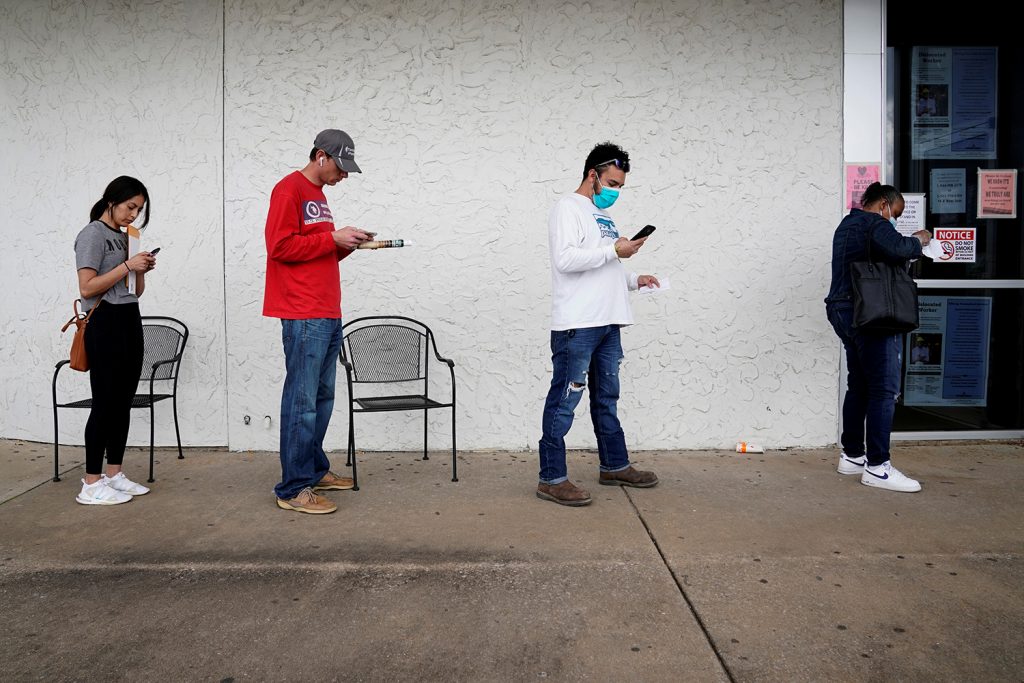

Image: People who lost their jobs wait in line to file for unemployment following an outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), at an Arkansas Workforce Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas, U.S. April 6, 2020. REUTERS/Nick Oxford