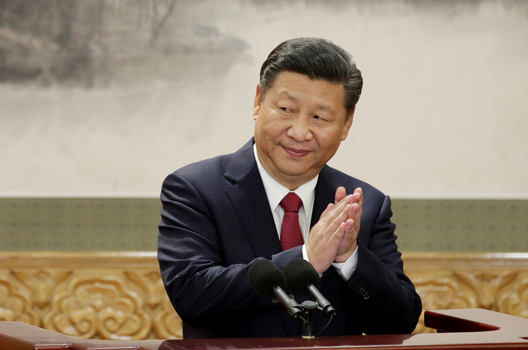

Chinese President Xi Jinping will arrive in Rome on March 21 accompanied by a 500-strong delegation. A number of economic agreements, including a widely discussed memorandum of understanding (MoU) on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), are expected to be concluded on the visit.

This MoU is not a trade agreement—only the European Union (EU) can sign trade agreements—but rather part of a political initiative that was launched in 2012 when eleven EU member states and five Balkan countries signed an MoU with China on investment, transport, finance, science, education, and culture.

In 2018, Portugal and Greece also signed the MoU, which simply certified what has already happened i.e. a heavy inflow of Chinese investment in the two countries. These investments occurred during the financial crisis that hit Portugal and Greece—a time when there was a desperate need for investment to boost confidence.

Why is Italy different? For two reasons. First, Italy’s economy is larger than that of all the other EU countries combined that signed the MoU with China. The potential impact on trade and investment to and from China is, therefore, much more significant.

Second, Italy is the first G7 country to sign an MoU of this kind with China. This raises the question whether the members of the G7—this club of Western economies that have so far acted jointly on geopolitical matters—are still on the same side.

Italy’s decision to embrace the BRI comes with risks and opportunities.

First the risks:

1) With its high public debt and low growth Italy is vulnerable. China tends to close deals with countries in such situations because the potential gains outweigh what it offers. There is a risk that Italy will agree to conditions that, over the long term, could harm its economy.

2) China’s strategy is to invest mainly through loans and not equity. In the energy and transport sectors, the vast majority of Chinese investment in the BRI countries has not implied direct investment. Usually, state-owned construction companies develop the initiative through loans provided by state-owned banks such as the China Development Bank. Multilateral financial institutions provide just 1 percent of the total investment in these initiatives. Procedures are blurred and there is a high risk that projects do not generate sufficient revenue to repay the debt. At present, $66 billion in Chinese loans within the BRI are non-performing loans.

There are many cautionary examples that highlight the risks of Chinese investment. In Sri Lanka, the harbor of Hambantota is a greenfield project financed by China. However, the Sri Lankan government did not meet the terms of the loan and was forced to give China a ninety-nine-year concession on the harbor and the adjoining land. Pakistan, meanwhile, sought a loan from the International Monetary Fund because of the large Chinese debt it has accumulated. In Europe, the government of Montenegro is struggling to repay its debt to China incurred through the construction of a motorway between the Port of Bar and Serbia.

3) Europe does not have a common strategy on key geopolitical issues. This has weakened its ability to negotiate as a united economic area. This is particularly relevant at a time when there is a need to put pressure on China to open up its market, apply the recently approved EU regulation of investment screening, or on crucial security issues associated with telecommunication.

However, opportunities also exist.

China is still an underdeveloped market for EU goods: only 5.5 percent of total EU exports go to China. Better networks would help grow the volume of EU exports.

Italy’s participation in the BRI might force the EU to speed up its negotiations with China to build reinforced trade and investment relations based on reciprocity.

For Italy, its participation in the BRI might reinforce its role as the logistic hub of Europe. So far, 70 percent of trade with China comes through maritime routes but only a small portion flows through Italy’s ports.

Given its location on the Mediterranean Sea, Italy has a comparative advantage relative to other EU countries. Europe’s two main ports of entry are in the north: Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Hamburg in Germany. This might explain why some EU countries do not approve of an MoU between Italy and China.

The MoU also holds an opportunity for the transatlantic relationship. The agreement between China and Italy can serve as a wake-up call for US President Donald J. Trump’s administration. Transatlantic trade and investment have been put at risk by Trump’s aggressive “America First” policy. It is then logical for EU countries to seek relationships elsewhere. This is what is happening as about half of the EU’s twenty-eight member states are already part of the BRI.

To preserve the transatlantic alliance it is imperative to speed up negotiations between the United States and the EU in order to quickly agree on a trade and investment partnership.

Instead of criticizing Italy, the EU and the United States should seize this opportunity to reinforce their alliance. The EU should also allow Italy to lead it in negotiations with China on fair and reciprocal trade and investment conditions. If this happens, it will be a win-win outcome.

Andrea Montanino is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program and a chief economist at Confindustria. Follow him on Twitter @MontaninoUSA.

Image: China's President Xi Jinping claps after his speech as he and other new Politburo Standing Committee members meet with the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China October 25, 2017. (REUTERS/Jason Lee)