This project, a collaboration between the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative and the Latvia-based Centre for East European Policy Studies, aims to advance understanding of Latvia’s defense and security policies, with an emphasis on resilience-building strategies. Latvia’s measures offer lessons for other frontline states, and demonstrate an increasing willingness to prioritize defense in an uncertain geopolitical environment. Read the other articles in this series here and here.

Ukraine’s resistance to Russian aggression has demonstrated an important lesson about national defense: it requires all levels of society, not just the military. It’s also not enough simply to respond in a crisis. It’s necessary to be prepared ahead of one.

Applying these lessons, Latvia has in recent years pursued a comprehensive approach to defense based on an understanding that every element of the government and population plays a part in creating a networked civil and military defense system. This approach grew out of necessity: Latvia is a small country with limited strategic depth. It also neighbors Russia, a large, aggressive military power that has attacked countries in its so-called near abroad.

Latvia’s approach, like those of its fellow Nordic-Baltic countries, is built on a straightforward idea: the country’s civil and military defense systems can achieve a greater deterrence and defense impact if they collaborate and if each part is prepared. To achieve this, Latvia has focused since 2014 on integrating all societal elements into its national defense. In practice, this has meant working to integrate municipalities and managers of public and private-owned critical infrastructure—such as energy, communications, financial services, and medical providers—into preparedness-building efforts.

Although this integration effort still has a ways to go, Latvia’s experience so far offers valuable lessons for other countries seeking better preparedness during a time of increased military and hybrid threats. Some of what Latvia offers by way of example in ensuring essential services during a crisis includes passing the relevant baseline legislation, encouraging public-private cooperation, expanding the coordination role of municipalities, and running training and preparedness exercises.

Boosting continuity of essential services and access to stocks

Latvia has shifted its crisis-management thinking from a focus on infrastructure protection to an emphasis on continuity of essential services and functions. Although this shift creates additional challenges for planners, it is based on the understanding that critical infrastructure cannot operate isolated from other national-defense factors.

In a meaningful step to implement this shift, Latvia introduced amendments to its National Security Law and its National Mobilization Law in 2021. These amendments resulted in the creation of a new, industry-specific critical-infrastructure category, which exempts from mobilization the personnel responsible for maintaining critical infrastructure and financial services. In the event of a major crisis, these workers have a duty to continue doing their regular jobs, which are necessary to ensure the continuous operation of critical services and industries that support the nation.

Working at the local level

Municipalities play an important role in nurturing a society-wide culture of preparedness and resilience. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 deeply resonated with Latvian society and created momentum for action. Latvians demanded that their local governments go beyond declaratory contingency plans to proactively explain preparedness plans to their own constituents.

Today, the necessary legislative basis has been adopted: the National Defense Concept (2023) requires that Latvian municipalities continue essential services in crisis or war and develop a society-wide culture of preparedness and resilience. Municipal preparedness plans related to war are developed in close cooperation with the National Armed Forces, and these plans must be exercised at least yearly in cooperation with the National Armed Forces.

Some municipalities have been more proactive than others. For example, Jelgava, which is the fourth-largest Latvian city in terms of population, created a municipal operation information center back in 2011, ahead of many other local governments in Latvia. In peacetime, this center serves as a municipal hotline for damaged infrastructure, but in a crisis, it serves as the municipal early warning system.

Setting expectations for public-private cooperation

Like in many other countries, owners and managers of critical infrastructure in Latvia are obligated by law to develop plans and standard operating procedures for continuity of their services (even if at a reduced level) during a crisis. Ultimately, companies are expected to be proactive about investing in their capacity and capability-building efforts and finding relevant in-house or external expertise to improve their preparedness. However, expertise and experience regarding continuity of critical infrastructure is highly specific and may be context dependent. Therefore, it may be a possible bottleneck in resilience-building efforts.

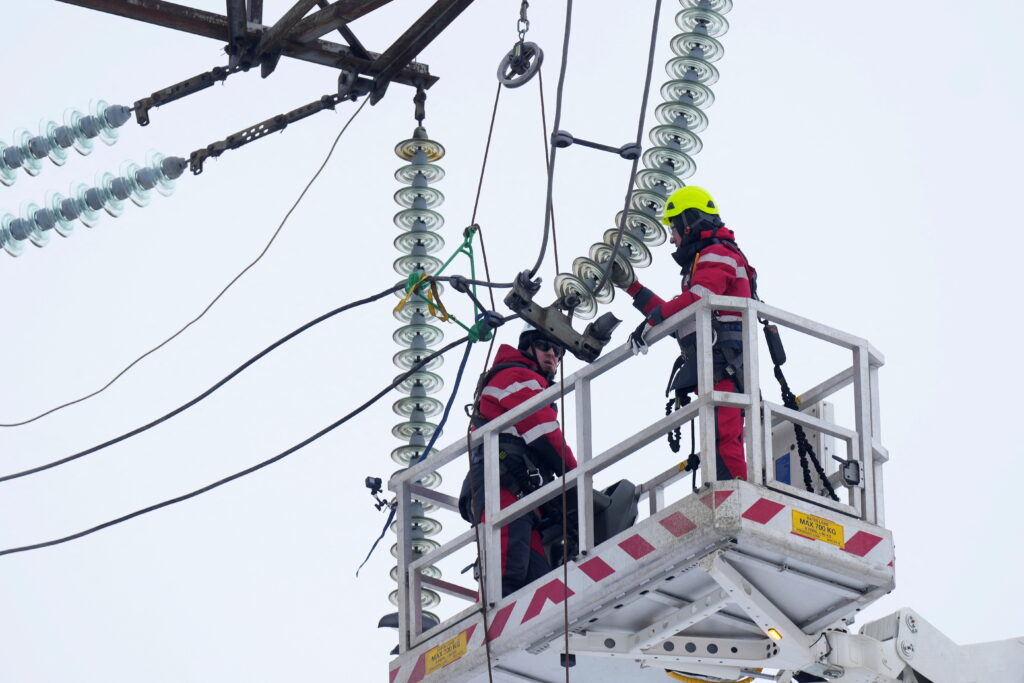

Some companies proactively seek to learn from the experiences of others. In one such case, the Latvian electric power transmission system operator Augstsprieguma tīkls organized open practical exercises for linemen, learning from the conditions in which Ukrainian linemen are operating.

Nevertheless, the Ministry of Defence and the National Armed Forces retain a key role in comprehensive defense planning, likely reflecting both the fundamental need to closely integrate military and civilian planning factors in comprehensive defense systems and the traditionally high level of societal trust in the National Armed Forces. Thus, even private industry’s preparedness plans are drafted in close cooperation with both the ministry of the specific field and the Ministry of Defence. This ensures that the government is aware of the resources in the civilian sector, able to provide expertise and experience, and can monitor how they fit in with the broader national resilience system. Moreover, industrial actors participate in exercises with the ministry of the specific field and the Ministry of Defence at least once every four years.

Public-private cooperation is also at the heart of securing food, water, and healthcare supplies. The Latvian Ministry of Agriculture plans and coordinates deferred procurement of food stocks in cooperation with municipalities, tasking food producers with being prepared to provide food in emergency situations. While the burden of preparedness responsibility is, again, placed on companies, municipalities have to identify industrial farms and food producers and wholesalers with storage capacity for finished products in their civil defense plans.

Ensuring access to cash and communications

The ability to ensure the flow of money in exchange for goods and services is another element of critical services. Societal upheavals, crises, and wars often undermine the ability to continue with peacetime payment systems, as Ukraine’s experience demonstrates. The Bank of Latvia (analogous to the US Federal Reserve) is developing cash and noncash crisis payment solutions for Latvian society that have a high adoption rate for noncash payments. For example, the Bank of Latvia is working with major commercial banks to develop Bank of Latvia–approved offline solutions to ensure individuals can use their bank cards to pay for basic necessities, even if bank communications are down. Similarly, during a crisis or war, banks are required to maintain the continuous operation of a predefined network of ATMs with at least one ATM per municipal center.

Latvia has sought to improve the integrity of its communications systems by ensuring that critical data—including sensitive healthcare, defense, security, and economic data—does not leave the territory of Latvia and that critical information technology systems continue to function without interruption even if the connection to the global internet is disrupted. To do this, the government now requires that national and municipal institutions, companies, and owners and managers of critical information-technology infrastructure prioritize using a single national internet exchange point, GLV-IX—a state-wide and state-operated local internet ecosystem—for their data flows if the outer perimeter of electronic communications is compromised.

Finding solutions to common preparedness-building challenges

Finally, Latvia has sought to address two common challenges among countries working to build preparedness: How can the government improve how it communicates preparedness requirements? And who pays for building resilience? Today, many national governments are increasingly concerned about how to communicate their preparedness and resilience expectations related to military crises and war with municipalities and private industries. Efforts such as disseminating information and issuing legislation need to be augmented by activities that encourage a thoughtful planning process, true understanding of the requirements, and knowledge development.

Indeed, Latvian municipalities have complained about the lack of resources to implement civil preparedness or insisted that preparedness should be handled on the national level. Likewise, even large and well-funded hospitals are struggling to store enough medicine and supplies to meet the three-month requirement of supplies, while smaller hospitals lack enough funding to meet the requirement.

Latvia has sought to address these questions through legislative changes, clarifying responsibilities and tasks, as well as mandating regular exercises. With time, continuous cooperation and the mandatory requirement of yearly exercises may also offer the parties involved a better understanding of the overall defense system, their own role within it, and therefore what to expect from their partners.

Regular exercise schedules may benefit Latvia’s preparedness across sectors by stress-testing the developed plans, developing knowledge, and informing the exercise participants of the potential challenges that their organization may be subjected to in case of a military crisis or war. For example, during the yearly state-wide comprehensive defense exercises Namejs, municipalities are involved in playing out different scenarios alongside the National Armed Forces. On a local level, Pilskalns exercises have been used since 2020 to test municipalities’ planning and practical response capabilities under a wartime scenario, involving national and local institutions, the National Armed Forces, and local companies. Ultimately, however, private enterprises must fund their preparedness planning and implementation activities.

Latvia has adopted a comprehensive national defense approach that integrates all levels of society and emphasizes proactive preparation where different levels of society—national and local governments, the public, and owners of critical infrastructure—are prepared to collaborate. Development of legislation promotes private-public partnerships, which in turn requires and enables municipalities, providers of essential services and owners of essential infrastructure to develop their own contingency plans to ensure uninterrupted operation during crises. Most importantly, regular exercises serve as a tool for stress-testing and self-reporting to ensure the plans are usable, as well as allow participants to gain experience implementing them and attain a better understanding of the entire defense system. However, financing and development of industry-specific expertise about continuity can serve as a potential bottleneck.

Latvia offers these important lessons; it’s the obligation and opportunity of allies and partners to learn from them.

Mārcis Balodis is a researcher and a Member of the Board of the Centre for East European Policy Studies. His primary research focuses on Russia’s foreign and security policy as well as Russia’s use of hybrid warfare.

Marta Kepe is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. She is also a senior defense analyst at RAND, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization.

This article is part of a series in partnership between the Atlantic Council and the Centre for East European Policy Studies.

Further reading

Fri, Feb 2, 2024

Russia Tomorrow: Five scenarios for Russia’s future

Russia Tomorrow By

A new Atlantic Council report explores five paths that Russia future might take in its future. What forces will shape Russia’s future?

Thu, Apr 24, 2025

Dispatch from the Kaliningrad border: Russia is fighting a long battle of attrition with the West

New Atlanticist By Tressa Guenov

Russia has repeatedly shown itself to be a threat to its neighbors and hostile to their ambitions for closer ties with the United States and the rest of Europe.

Thu, Apr 24, 2025

Dispatch from Vilnius: A NATO ally in Russia’s shadow won’t let history repeat itself

New Atlanticist By James Hursch

The United States is urging its allies to strengthen their own defenses. To ensure it is never again dominated by Moscow, Lithuania is doing just that.

Image: Specialists of the Latvian independent power transmission system operator prepare to cut a loop of power line from Russia after decoupling from their power grid, near Vilaka, Latvia February 8, 2025. REUTERS/Ints Kalnins