Rivalry between the United States and China is deepening in the Asia-Pacific and beyond. While China is actively promoting its Belt and Road Initiative, the United States, together with its allies and partners, has put forward a Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. Both the United States and China are asking countries in the region to make a strategic choice between the two competing conceptions, making it difficult for partner countries to live in both worlds.

Countries in the region, especially small countries, fear being squeezed between these two strategies, and rather hope to access both without being forced to choose. As Singapore’s prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, said at the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in November 2018, “it’s very desirable for us not to have to take sides, but the circumstances may come when ASEAN may have to choose one or the other. I am hoping that it’s not coming soon.”

South Korea, like other countries in the region, is trying to avoid both being abandoned by its allies and friends and becoming entrapped by the rivalry between the United States and China. How then can South Korea navigate between two competing strategic options? Should Washington be concerned that Seoul may choose Beijing?

Stuck in the middle?

South Korea has no reason not to participate in Washington’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. South Korea has prospered thanks to the US-created liberal international order that has sustained free trade, free navigation, and free communication. A free and open Indo-Pacific will be vital for South Korean trade as the oceans in this region serve as throughways for more than 30 percent of South Korea’s exports and more than 90 percent of its oil and natural gas imports. Without a secure, stable, and reliable Indo-Pacific, South Korea’s security and economic growth can hardly be sustained.

Then, why is South Korea maintaining strategic ambiguity instead of forthrightly supporting Washington’s strategy?

First, South Korea wants to avoid being trapped in a rivalry between the United States and China. The Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy seeks to contain China and weaken Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

South Korea is not necessarily in favor of the Belt and Road Initiative, but it has reasons to avoid antagonizing Beijing. China is South Korea’s biggest trading partner, with exports to China accounting for 26.7 percent of total South Korean exports—larger than the combined volume of South Korean exports to the United States and Japan.

In addition, Chinese participation in the international sanctions regime against North Korea is crucially important to the effort to convince Kim Jong-un to give up his nuclear weapons. Any hope of unifying the two Koreas will require buy in from Beijing, making it imperative that Seoul not antagonize China. Instead of balancing China, South Korea prefers hedging against China.

Second, South Korea’s hesitation about the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy stems from its number one priority: North Korea. As the ongoing diplomatic effort with Pyongyang presents a meaningful opportunity to denuclearize North Korea, South Korea must ensure its success. As a result, Seoul will not risk embracing a wider regional framework like the Indo-Pacific if it perceives such action as impeding its goal of denuclearization.

New dynamics

Despite South Korea’s dueling priorities, there are reasons to think that South Korean hesitation about working with the United States, Japan, Australia, and India on a Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy could be abating.

Chinese retaliation against South Korean firms after the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-ballistic missile defense system in Seongju has reawakened South Korean awareness about Chinese hostility. China disregarded South Korea’s legitimate reasons to deploy THAAD to defend against North Korean missiles and unilaterally took action against the South Korean firms.

Meanwhile, South Korean firms, which face unprecedented challenges in the Chinese market, are beginning to find new outlets. There is a growing feeling among South Koreans that China is not a reliable partner. This should drive Seoul to work more with democratic friends on the basis of the rule of law, free trade, fair treatment, and transparency.

Suspicious of China and spurred by the need to establish a new market, South Korean firms are increasingly investing in Southeast Asian countries. ASEAN nations and India, with their lower wages, growing market potential, and increasing population have become attractive production bases for big South Korean firms.

By promoting private investment, instead of the state-sponsored or state-led investment of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, South Korea offers a much more attractive model to the region. A few Southeast Asian countries, including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Malaysia, have racked up mountains of debt and a worrying overreliance on Beijing. While many of these countries fear Chinese economic domination, South Korea has long been involved in international development projects for underdeveloped and developing countries through overseas development assistance. South Korea can lean into this reputation and create new partnerships with, not domination over, developing countries in the region.

South Korea in the Indo-Pacific

South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s New Southern Policy targeting ASEAN nations and India clearly overlaps with the conception of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. Though Seoul could still work with the Belt and Road Initiative as well, it has much more to gain from working with the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy as it emphasizes openness, transparency, and inclusiveness.

While Washington is concerned that South Korea has not unambiguously chosen its preferred course, it should not doubt that Seoul will be a strong partner for the Indo-Pacific strategy.

South Korea can launch and push forward multiple projects within the Indo-Pacific strategy. These include:

Infrastructure: South Korea has completed numerous infrastructure building projects in developing countries either independently or in partnership with international firms. South Korean firms have proven international competitiveness in building not only roads, railroads, schools, hospitals, and dams, but also engaging in largescale projects such as energy supply, plant construction for industrial complexes, power plants, airports and ports, among others.

Training and cooperation in law enforcement: South Korea, which itself transitioned from a developing to advanced economy, has significant experience in how to fight corruption, economic malpractice, social ills, and public abrogation.

Maritime security and safety of navigation: The South Korean navy played a pivotal role in protecting commercial ships from pirates in the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia and Yemen. It could use that experience to lead efforts against piracy, smuggling, illegal immigration, and human trafficking in the Indo-Pacific.

Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief: Both sets of aid can be more effective if countries collaborate. South Korea can help maximize gains by engaging with its partners.

Environmental protection: As countries develop steps must be taken to protect the environment. Securing clean water, clean air, and a clean living environment are indispensable part of such an effort; collaboration beyond national borders is critical to its success.

Increasing connectivity: Connections via land, ocean, cyber, and space are increasingly important for upgrading transactions, transportation, and communication. Improving Internet quality, safeguarding cyber and space security for protecting privacy while promoting transparency, maritime connectedness for trade, and communication are all important areas of cooperation.

Nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction: South Korea can play a pivotal role in preventing, blocking, and investigating any North Korean attempts to proliferate weapons of mass destruction.

Cheol Hee Park is a visiting senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and professor at Seoul National University’s Graduate School of International Studies

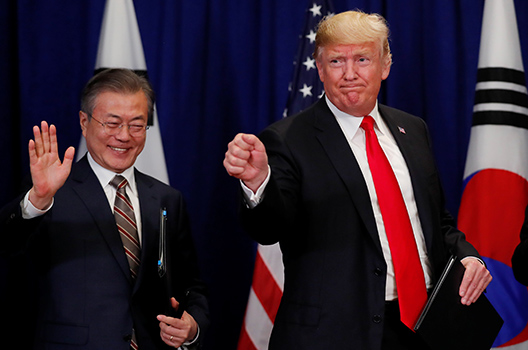

Image: US President Donald Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in gesture after signing the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement on during a ceremony on the sidelines of the 73rd United Nations General Assembly in New York, US, September 24, 2018. (REUTERS/Carlos Barria)