The United States government has apparently struck a blow against the Iranian nuclear enrichment capability by using Stuxnet to disable centrifuges. While this cyber weapon destroyed centrifuges and seized up the enrichment process, the cost in American cyber power ultimately will not have been worth these limited gains.

On the plus side, the United States has struck against some of the world’s most terrible organizations working towards the world’s most horrible weapons. If the Iranians ever did build and use a nuclear weapon, we would have regretted missing any chance to disrupt that process. Given the implications, it is understandable that two US presidents authorized and continued a covert program of cyber force to disrupt Iranian nuclear ambitions.

However, not all good ideas, and even fewer covert ones, should be executed. Though it did not cause any physical damage outside of the intended target of Iranian enrichment plants, Stuxnet somehow sprung loose from its intended target and spread in computers – and headlines – around the world. And this leak (along with those from the White House) led to the many downsides.

Few in the world will ever believe the peaceful motives of the United States in cyberspace again, giving us even less leverage to ensure this new cyber dimension develops in a way encompassing America’s wider economic and security interests.

Cyberspace is “the backbone that underpins a prosperous economy and a strong military and an open and efficient government,” according to President Obama. Because of this importance, not much more than a year ago, the president committed the United States to “work internationally to promote an open, interoperable, secure, and reliable” cyberspace “built on norms of responsible behavior.” He wrote that, “While offline challenges and aggression have made their way to the digital world, we will confront them consistent with the principles we hold dear: free speech and association, privacy, and the free flow of information. The digital world is no longer a lawless frontier … It is a place where the norms of responsible, just and peaceful conduct among states and peoples have begun to take hold. “

Stuxnet was not an act of peaceful conduct.

Saying one thing in public while doing the opposite covertly in the shadows happens of course all of the time between governments. China is, for example, behind large-scale global cyber espionage at the same time as it asserts that such acts are illegal and forbidden.

But the United States is the one that very publicly got caught and the timing could hardly be worse. The future of the Internet is being decided and post-Stuxnet, more nations are likely to side with the Russians and Chinese.

Even before this news, American technologists and diplomats were fighting to keep the International Telecommunications Union from taking a much greater role in the operations and architecture of the Internet. An Internet run by the ITU, an arm of the United Nations, is not in the US interests as it would be run by one-country, one-vote with no voice for civil society or technology companies. Cyberspace would likely become Balkanized, an interconnection of separate national networks with dire consequences for the freedom of speech and commerce. In this future, the architecture of the Internet will have Chinese and Russian characteristics, much friendlier to eavesdropping and blocking information embarrassing to closed or repressive regimes. Our diplomats are also more likely to be outflanked by the apparently more “peaceful” Chinese and Russians as the UN Group of Government Experts convenes this August to try to agree on new international cyber norms.

Indeed, now that this genie is out of the bottle, the United States will be blamed for every piece of sophisticated malware from now on. Other nations and non-state criminals will get free passes – they conduct attacks too, but we’re the ones that got caught.

The most important reasons why Stuxnets are not in US interests revolve around the basic argument that “those with glass industrial control systems should not throw stones.” The United States has incredibly vulnerable cyber systems, including in critical infrastructures like the electrical generation and transmission systems. Not only has the United States legitimized attacks against these systems, they are now likely open to direct reprisal from Iran.

DHS officials have testified to Congress they are “concerned that attackers could use the increasingly public information about [Stuxnet] to develop variants targeted at broader installations of programmable equipment in control systems.” General Alexander of US Cyber Command similarly told lawmakers that “Attacks [such as Stuxnet] that can destroy equipment are on the horizon, and we have to be prepared for them.” The government has been clear about the proper response to Stuxnet and other threats with Alexander writing to Congress that “Recent events have shown that a purely voluntary and market driven system is not sufficient. Some minimum security requirements will be necessary” using regulation to secure critical infrastructure.

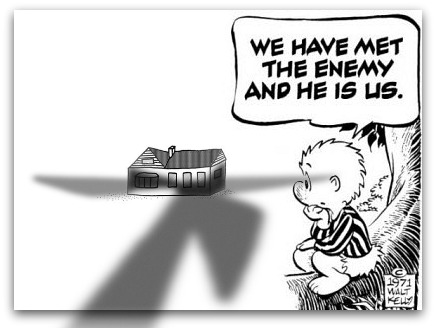

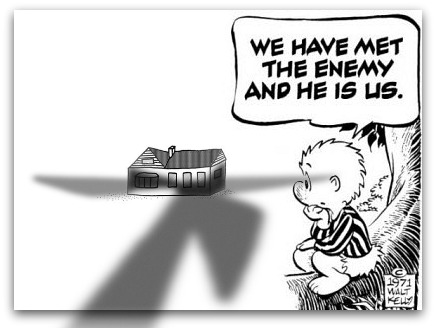

The message to the US private sector therefore seems to be that they need to be regulated because they are not protecting themselves sufficiently against a weapon designed and launched by their own government. The arsonist wants to legislate better fire codes.

Of course, this is too simplistic an argument: crime and espionage are the major risks and there have long been ample disruptive threats besides Stuxnet looming over our critical infrastructures. While true to a point, these facts are increasingly irrelevant. The United States appears to have struck first in cyberspace and the private sector will not want to be stuck with the bill.

If Obama was speaking the truth when he said “America’s economic prosperity in the 21st century will depend on cybersecurity” then it is unlikely Stuxnet is in our long-term interest. It slowed the Iranian nuclear program down, but does not seem to have caused extended disruption; it was, therefore, a tactical rather than a strategic win. Unfortunately, it may have torpedoed American credibility on all future cyber issues and could be remembered as the equivalent of the invasion of Iraq: a mistaken use of force against weapons of mass destruction. Ultimately it may help deliver a strategic loss to the United States. Rather than seen as inventing and nurturing cyberspace, we may seem to digital natives as a crotchety old man, a declining imperial power lashing out as the domain of its own making slips ever more out of its influence.

The United States has now made the “demonstration” attack that some in Washington DC believe is needed to deter our adversaries. As General Cartwright expressed, “You can’t have something that’s a secret be a deterrent. Because if you don’t know it’s there, it doesn’t scare you.”

With Stuxnet, we now have other nations scared of us in cyberspace. Perhaps, like General Cartwright wants, this will be for the best … but like so much else in cyberspace, this answer is still to be discovered.

Jason Healey is the Director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council of the United States. You can follow his comments on cyber cooperation, conflict and competition on Twitter, @Jason_Healey.

Image: pogo-we-have-met-the-enemy.jpg