Winston Churchill said “The only thing that ever frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril”. Last Friday in Moscow’s Victory Park I had the honor of an escorted visit to the Hall of Memory and Sorrow in which 2650 ‘teardrops’ commemorate the 26.5 million Russian war dead. It was a truly moving experience. Here in Oslo in support of a NATO meeting I am reminded of the enormity of the Allied effort to defeat Nazi Germany.

This week sees not only the seventy-second anniversary of the sinking of the German fast battleship Bismarck, but also the seventieth anniversary of what the U-boat arm called “Black May” when over forty U-boats were lost to new British tactics and technology. It is seen as the turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic and for that reason marks the commemoration of what was the longest campaign of World War Two.

The sheer scale of the battle speaks for itself. It lasted the entirety of the war from September 1939 to May 1945. Simply to stay in the war Britain had to import one million tons of food and materials each week. Three thousand five hundred merchant ships were lost with some thirty thousand sailors killed. The massive bulk of those lost were British but there were also American, Canadian, Danes, Dutch, French, Norwegian and a host of other allies who suffered casualties. One hundred and seventy-five allied warships were sunk but seven hundred and eighty three U-boats were also sunk. Indeed, ninety per cent of U-boat crews were killed. Only RAF Bomber Command comes close to that casualty rate with some fifty percent of crews killed.

Nor was this simply a sea war with the RAF, Royal Canadian Air Force and US Army Air Force playing a critical role in the eventual victory. There were over one hundred major convoy battles and over one thousand single ship engagements. Attacks came not just from under the waves but also from German air and surface raiders. Moreover, the convoys did not simply sail between North America and Britain. In what Churchill described as the “worst journey in the world” one of the decisive campaigns was the successful re-supplying of the Soviet Union by convoys from Britain to Murmansk in the Soviet high north.

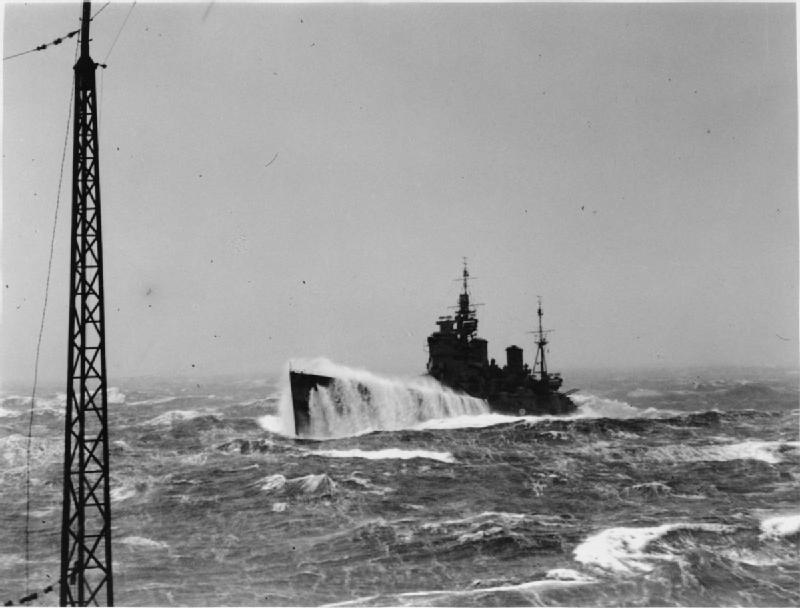

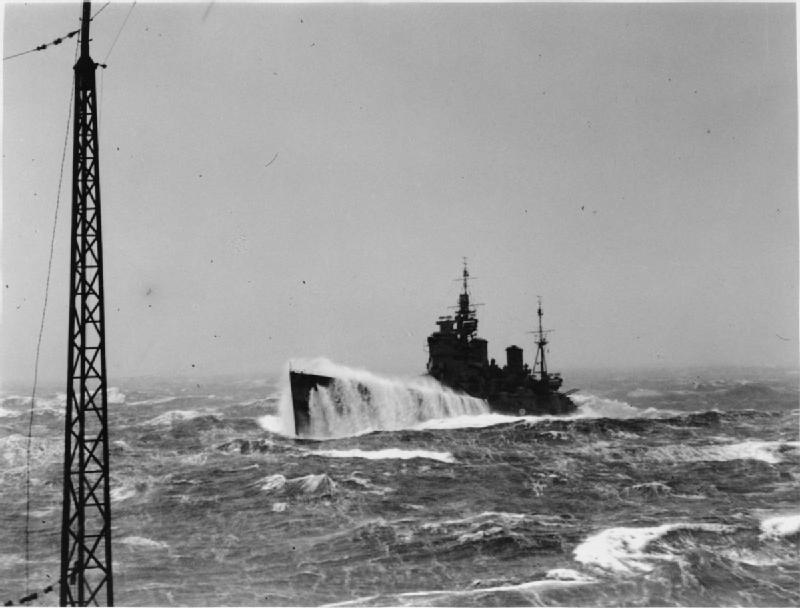

Whilst not immediately obvious to Russians the Battle of the Atlantic was critical not simply to Britain’s survival but that of the Soviet Union. The Murmansk convoys suffered terribly from air, sea and U-boat attacks launched from bases here in occupied Norway. Critically, on 26 December, 1943 the British battleship HMS Duke of York cornered and sank the German battle-cruiser Scharnhorst. The Battle of North Cape was one of the last battleship-to-battleship duels in which air power played no meaningful role. As a sign of things to come it was the first occasion when radar-controlled gunnery was used. In the Arctic twilight HMS Duke of York completely surprised the Scharnhorst with her massive fourteen inch guns straddling and hitting the German ship with her very first salvo.

Ultimately, the battle was an exercise in British sea power which still has lessons for today. Specifically, why Britain must retain a powerful navy able to reach those parts most other navies cannot. Ninety-five per cent of all British trade goes by sea and with sea-lines of communication (SLOC) ever more important to global trade keeping sea-lanes open is a vital British interest.

There is another reason. The Royal Navy remains a ‘strategic brand’ one of those iconic services the history of which makes it far more than any old navy. If the Royal Navy is weak, as it is dangerously close to being today, then not only Britain’s defense but British influence is at risk. This is something all too apparent to me when I visit Washington, Moscow, Beijing or indeed Paris or Berlin. National wealth stands ultimately on national influence. It is something too many British politicians fail to understand. Even more worrying too many of those with responsibility for planning Britain’s future military also fail to understand this basic power truism in what is still a world driven by state power.

On Sunday the last remaining veterans of the Battle of the Atlantic gathered in Liverpool Cathedral for a service of remembrance. The Port of Liverpool had been the hub of the Battle of the Atlantic. Although now few in number they remain stout of heart. The role they played was to critical in the winning of the war. We owe our freedom to the thousands of Britons, Americans, Canadians and those of many other proud lands who surrendered their lives to the chill depths of the Atlantic during that terrible time.

Honor them.

Julian Lindley-French is a member of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Advisory Group. This essay first appeared on his personal blog, Lindley-French’s Blog Blast.

Photo credit: Imperial War Museum

Image: hmsdukeofyork.jpg