US and Chinese trade negotiators will meet again in Washington on January 30 amid escalating bilateral tensions over issues far broader than traditional trade policy. The meetings will occur in a fittingly freezing city, with plunging temperatures outside accompanying the deep freeze that has gripped the bilateral relationship. US allies in Europe and Japan will quietly cheer from the sidelines as US policy makers prepare to take a tough stance.

With the ninety-day negotiating window to find a solution to the US-China trade tensions quickly running out and with expected February action by the United States regarding foreign automobile tariffs, the stakes are high. The scope of discussions is also broad. It is highly unlikely that all policy disputes between Beijing and Washington can be resolved in the January 30 meeting.

As the Atlantic Council’s David Wemer noted in the New Atlanticist on January 27, the Chinese delegation arrives in Washington amid renewed US efforts to stem intellectual property (IP) theft and corporate espionage by Chinese companies. The shape and scope of the current drama illustrates just how far the trade policy paradigm has shifted away from traditional trade in goods.

It is helpful here to note that a classic “trade war” technically is not underway. At least, not yet. As Martin Feldstein underscored January 29 in a commentary for Project Syndicate, trade wars are traditionally characterized by using trade remedies to enhance target liberalizations. If the policy priority is to reduce the trade deficit in goods and the tool is tariffs, then an offer by the targeted party to adjust purchasing activity in order to address the deficit should resolve the conflict. Instead, Feldstein points out, trade policy is looking increasingly asymmetrical since Chinese offers to adjust buying behavior are not generating concessions from the United States regarding non-trade issues such as IP theft.

It is true that the Trump administration has consistently complained about the bilateral trade deficit with China regarding goods. The rhetoric has encouraged many to believe that the United States is lurching toward a “managed trade” policy rather than a free-trade policy in order to reduce the deficit. Economists fume that a focus on the bilateral trade in goods deficit itself is a misleading indicator of any aggregate bilateral trading relationship. I have argued here and here in the New Atlanticist that the focus on the goods sector generally is inappropriate and short-sighted since it ignores the much larger and more strategically significant services sector alongside non-tariff barriers to trade. This is accompanied by the fact that a trade deficit is not necessarily a bad thing; it reflects the combination of a strong economy and increased purchasing power as well as the principle of competitive advantage. Moreover, the US shift away from manufacturing is more than offset by the recent increase in services exports, where the innovation-rich technology economy delivers a substantial trade surplus.

Chinese policy makers have responded to US rhetoric by offering to increase purchases of US goods, including agricultural goods, at volumes sufficient to eliminate the trade in goods deficit. The offer might have been more credible had Chinese purchases been more consistent. For example, in November 2018, Chinese purchases of US soybeans plummeted to zero.

But the more important point is that US policy makers are giving every indication that concessions on the less important (but politically powerful) agriculture and goods sectors will not be sufficient to mollify negotiators who are more focused on strategically significant 21st century sectors, such as 5G networks and handheld communications devices.

The standoff illustrates well the brewing battle underway globally as trade policy makers attempt to transition the post-war trading framework to address traditionally non-trade areas. Viewed from this perspective, the IP theft drama taking center stage in the bilateral US-China trade talks may best be viewed as a new kind of trade war in which old economy tools are used to achieve concessions on new economy sectors.

The United States is Not Acting Alone

Contrary to popular belief and official sector rhetoric, the United States is not alone in taking a tough stance against China on IP theft. In January alone, a range of key US trading partners signaled solidarity with the United States. The most notable developments include:

- Canada: Law enforcement officials in Canada detained and offered to extradite a senior Huawei executive not long after the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was finalized.

- European Union: The European Commission on January 9 published statistics showing that Europe—not China—is the largest export market for US soybeans. It also promised to increase European purchases of US soybeans for biofuels use. Policy makers on January 29 implemented that promise, roughly twenty-four hours before bilateral US-China trade talks were set to begin in Washington. At the beginning of the year, EU officials filed with the World Trade Organization (WTO) their plans to extend their own steel tariffs. The move brought the EU into harmony with the United States regarding imports of Chinese metals.

- Japan: Leaks to the Japan Times indicate that policy makers in Tokyo are proceeding slowly regarding a bilateral trade deal with the United States. The shift in momentum leaves the US Trade Representative free to focus on Chinese talks.

These traditional US allies share with Washington a strategic interest in encouraging Beijing to operate within the umbrella of post-war trade structures that prioritize private sector economic activity over official sector market involvement. They are taking a range of actions that effectively increase the bargaining position of the United States with respect to the services sector and a range of non-trade policy priorities. As the Center for Strategic and International Studies recently noted, “China has altered its policy mix in ways that are inimical to market economies and the liberal international order they have built.”

The differences between Chinese policy priorities and US policy priorities indeed run deep. They go to the core of what it means to be a market economy. These differences between Beijing and its trading partners will not be resolved in one single meeting or all at once. The differences will be ironed out slowly, as policy makers in parallel rebalance expectations and priorities about the gains associated with globalization and the ongoing technological revolution. Volatility, uncertainty, and major inflection points are inevitable as policy makers globally negotiate a new institutional equilibrium with a fast-evolving China.

What Comes Next – The Jagged Path to a New Equilibrium

Negotiations among peers is never pretty and the US-China trade relationship is no exception. While the bilateral trade relationship between the United States and China is complex, it is not binary. There are more issues on the table than just IP theft or metals tariffs. In addition, the cross-border reaction function from policy makers outside the “room where it happens” in Washington has a material impact on how trade disputes are resolved. The reaction from Europe and Japan and Canada to today’s meetings will be at least as important as the reaction among policymakers on both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. The next inflection point will therefore be on February 7, when the EU’s Trade Commissioner meets with stakeholders in the Expert Group on EU Trade Agreements. The Commission indicates today that the agenda will expressly include discussion of the transatlantic trade talks.

Economic diplomacy generates jagged progress across multiple issues and in multiple platforms, not a linear progression of wins and losses. The trade meetings this week in Washington will be no exception. The meeting’s outcomes will most likely contribute insight into how the Trade in Services Agreement and WTO reform initiatives will progress even as the two parties talk their way through tariff and theft pressure points. Assigning a win/loss rate on individual issues is at least as misleading an indicator of policy trajectories as a singular focus on the goods deficit.

The good news is that the global trading system has been here before. When policy makers met at Bretton Woods in 1944 to craft the current international and multilateral system, the parties at the table included China and Stalin’s Soviet Union, both which rejected free market principles. If wartime leaders could manage to craft the current architecture that has delivered significant growth globally for decades, it is reasonable to believe that today’s leaders can manage at least to avoid classic, debilitating trade wars.

Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program. She has served as a senior US government official in Brussels as the first US Treasury attaché to the European Union and in Washington as senior counsel to the US House of Representatives’ Financial Services Committee. Follow her on Twitter @BCMstrategy.

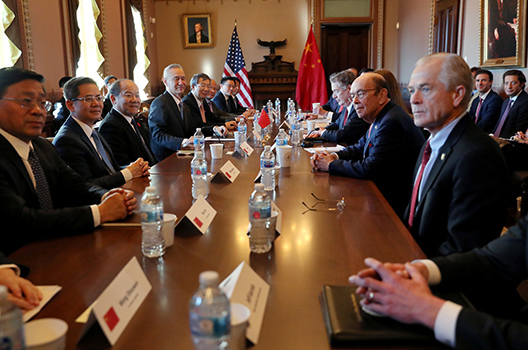

Image: US trade representative Robert Lighthizer, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow and White House trade adviser Peter Navarro participate in a photo-op with China's Vice Premier Liu He, Chinese vice ministers and senior officials in the Diplomatic Room in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on the White House campus in Washington, US, January 30, 2019. (REUTERS/Leah Millis)