Even as the United States celebrates the beginning of its chairmanship of the Arctic Council, it hesitates to take leadership in the Arctic region. This reluctance highlights a dichotomy between US strategic interests in the Arctic and that of every other Arctic power which, if not addressed, increases the likelihood of regional instability.

Even as the United States celebrates the beginning of its chairmanship of the Arctic Council, it hesitates to take leadership in the Arctic region. This reluctance highlights a dichotomy between US strategic interests in the Arctic and that of every other Arctic power which, if not addressed, increases the likelihood of regional instability.

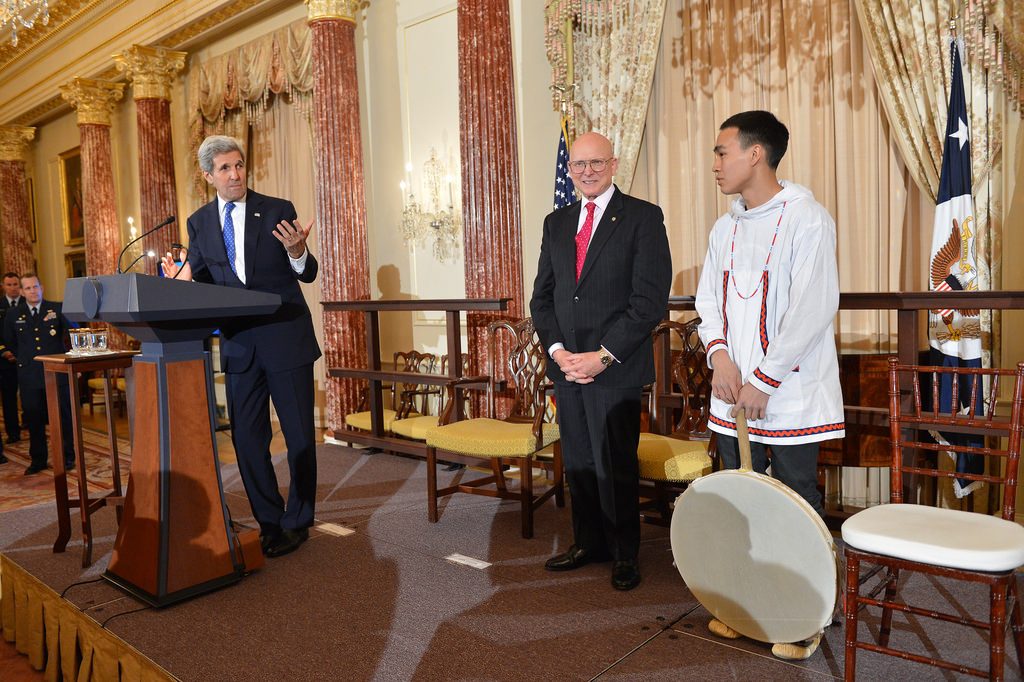

At a May 21 reception to mark the handover, US Secretary of State John Kerry said Washington’s priorities “include Arctic Ocean safety, security, and stewardship.” He reassured the audience that this is “a shared responsibility,” ensuring that the US role would be one among many.

When the United States took over the mantle of the Arctic Council from Canada on April 24, Kerry commented to the press: “Every action that the Council takes requires collaboration, so we’re very grateful to have partners who are all intent on getting things done.” Kerry elaborated on what US chairmanship for the council would look like: “The theme of our chairmanship is ‘One Arctic’ … which embodies our belief that the entire world shares a responsibility to protect, to respect, to nurture, and to promote the region.”

While some observers of the United States in different global arenas might be surprised by its hesitancy to assume more assertive leadership in this region, those familiar with US Arctic policy are not. Robert Huebert, a political science professor at the University of Calgary, echoes the sentiments of many when he describes the United States as a “reluctant power” in the Arctic, unwilling to commit political capital or a significant budget to the region.

Is the Arctic the one region where the United States is truly committed to multilateralism? Recent shifts might indicate otherwise. Last year the United States established the position of Special Representative for the Arctic, which is now filled by retired Coast Guard Adm. Robert Papp. The United States has updated its official Arctic policy twice in recent years, in 2009 and again in 2013. The Obama administration recently authorized Royal Dutch Shell to drill for oil and natural gas off Alaska’s Chukuchi Sea. The Pentagon has also made some efforts to restructure its forces to be able to respond to Arctic security threats.

Some think that’s not enough. Andrew Holland, a Senior Fellow for Energy and Climate at the American Security Project, recently wrote that “the United States has notably combined only tentative policies with very little funding and no high-level political visibility.” No other Arctic nation shares Washington’s laissez-faire attitude towards the region, and while the United States publishes policy papers, other countries and observers are pursuing and developing a legitimate Arctic foreign policy.

The easiest and most accepted way to boost regional engagement is through a process the United States has not yet made available to itself: pursuing additional territorial claims in the Arctic under the UN Treaty on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS). Under UNCLOS, signatories have ten years from the date of ratification to claim an extended continental shelf. Four of the five states bordering the Arctic Ocean—Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Russia—have ratified UNCLOS and have attempted to extend their Arctic claims accordingly. If deemed valid, these claims give exclusive rights to the sea bottom in the claimed territory and any resources in the area.

Norway submitted its claim for additional Arctic territory in 2006, Canada in 2013, and Denmark in 2014. However, no nation has pursued the process with the same zeal as Russia, which last year claimed that a vast portion of the Arctic—including the resource-rich Lomonosov Ridge—is actually an extension of the Siberian continental shelf. Since the United States has not yet ratified UNCLOS, it cannot make any territorial submissions according to international law.

Access to the region could present another problem as the US Coast Guard possesses only three naval icebreaker ships—the same number as Estonia, half as many as Canada, and about forty less than Russia. Even worse, of the three US icebreakers, only one is an operational heavy icebreaker. When informed by Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) at a May 2015 congressional hearing that in terms of everything from icebreakers to Arctic infrastructure the United States “may be forty years behind,” Defense Secretary Ashton Carter replied: “I think it’s fair to say we’re late to the recognition of that.”

How can the United States lead in a region where it is less engaged than any of its partners and rivals? Despite Washington’s claim that it wants its leadership of the Arctic Council to be one of cooperation and consensus, the Obama administration should not deceive itself into thinking that other nations will be willing to follow its lead in the Arctic until it shows the same kind of interest in the region they do.

John-Daniel Kelley is an intern in the Atlantic Council’s Millennium Leadership Program.

Image: Secretary of State John Kerry delivers remarks at the US Chairmanship of the Arctic Council reception with Special Representative for the Arctic Adm Robert Papp at the State Department in Washington May 21. (Photo courtesy of the State Department)