On May 10, the United States raised tariffs from 10 percent to 25 percent on $200 billion of imports from China, affecting about 5,700 categories of goods and covering almost one-third of capital and consumer goods. The new 25 percent tariff rate won’t apply to goods in transit—those that left China before May 10 and arriving in the United States before June 1. This delays the economic impact of the measure by a few weeks which can be helpful given the US deadline of one month before imposing a 25 percent tariff on the remaining $300 billion of Chinese imports.

In response to the US tariffs, China has raised tariffs to up to 25 percent on $60 billion of imports from the United States. These tariffs will come into effect on June 1. In addition, China can use non-tariff means to further reduce US imports, including by directing state-owned enterprises (SOEs) not to buy US goods and making it harder for US companies to operate in China. For example, US exports of soybeans and grains to China have collapsed since September 2018 as China retaliated against US tariffs. But increasing non-tariff barriers will make the process much more opaque and its impact difficult to estimate and reverse.

China’s Ministry of Commerce said that “it deeply regrets the US decision… [and] will have to take necessary countermeasures… but hopes that the two sides can resolve the issue… (with) the US meeting us half way.”

Protracted Negotiations

Despite this escalation, both the United States and China have agreed to continue talking, even though no new meeting has been scheduled. There seems to be room for compromise on several issues such as protection of Intellectual Property (IP) rights, forced transfer of technology, and Chinese commitments to purchase more US goods. The Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress amended three laws in late April (the trademark law, the law against unfair competition, and the administrative licensing law) to strengthen the protection of IP rights. These laws can be amended again, if necessary. Moreover, China’s royalty payments to global IP holders have increased significantly from $1.4 billion in 1999 to $27.2 billion in 2017, second only to the United States at above $40 billion. Beijing could respond to US pressure by beginning to fully honor all IP rights with increased royalty payments.

Reaching an agreement on two core issues will be more difficult. The first is the subsidies the Chinese government gives to its SOEs, especially in strategic sectors, such as those specified in the “Made in China 2025” development plan. The US Trade Representative (USTR) Office has estimated that such subsidies amount to $500 billion and give Chinese corporations unfair advantages over the United States and other players in both domestic and international markets. Since such subsidies are at the core of the Chinese economic and political system, it is difficult to see China agreeing to any meaningful changes. Probably the most that can be expected are commitments to improve disclosure, along the lines of the World Trade Organization’s requirement that member states notify the organization of any subsidies to SOEs (which Washington has accused China of failing to honor).

Second is the issue of enforcement. There can be a compromise agreement on a symmetrical mechanism whereby both the United States and China can monitor compliance to the agreement, call each other out, and take remedial measures. A unilateral enforcement system whereby only the United States can keep most, if not all, of the current tariffs and can impose additional ones if it judges that China is failing to comply with any agreement—without China being able to retaliate—constitutes a challenge to China’s sovereignty and will be very difficult for its leadership to accept, particularly against the backdrop of rising nationalist sentiment. This year starts a series of commemorations for anniversaries important to China and Chinese President Xi Jinping: the May Fourth Youth Movement in 1919 that kicked off China’s anti-colonialist struggle, the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921, and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

US-China trade negotiations will remain protracted with the likelihood of even more tension. Beyond tariffs, both Congress and the administration are planning measures to tighten export control and restrict foreign investment from China especially in strategic, high-technology sectors. The implementation of these measures will cause more friction with China.

In addition, US sanctions, especially on Iran, Venezuela, and Cuba can also erupt into confrontations with China (such as the case against Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou who is going through extradition proceedings in Canada). In short, expect ongoing tension and friction between the United States and China for the foreseeable future.

Impact of the Trade War

The longer tariffs and trade tensions last, the more damage will be done to the US, Chinese, and global economies.

Until today, US tariffs have had a modest impact on economic growth. US tariff revenue increased to $75 billion in Q1 2019 on an annualized basis. The average range of annual tariff revenue was $30-$40 billion between 2010 and 2018. US President Donald J. Trump has repeatedly said that tariff revenue is a good thing, “having enriched” the United States. He is only half right: the US Treasury has received more revenue but essentially as a result of a tax increase on US businesses and consumers who pay practically all of the tariffs, not the Chinese producers (who suffer because of lower sales due to the declining competitiveness of their products in the US market). The hidden sales tax increase will probably offset what’s left of the stimulative effect of the tax cuts given by the Trump administration in 2017. One concrete example of the cost-benefit comparison: the price of washing machines in the United States has risen by 12 percent since the January 2018 tariff. The higher prices have been estimated to cost US consumers an extra $1.5 billion—or almost twenty times more than the extra tariff revenue on an annual basis.

The new 25 percent tariff of $200 billion of imports from China, if maintained for a full year, has been estimated to reduce real gross domestic product (GDP) growth by one quarter of a percentage point in the United States and about three quarters of a point in China. If Trump were to impose a 25 percent tariff on the remaining $300 billion of imports from China, the negative impact on growth would be twice as severe. While it takes time for the negative effects to materialize, slower growth and falling equity markets would create incentives for both Trump and Xi to strive for a compromise to settle the dispute—in other words, things will have to get worse before they get better.

The Global Impact

The US-China trade war will also impact other countries in a mixed and complicated way. Some will benefit from a diversion of trade and investment flows from either country. For example, Brazil has benefitted from China cutting back on purchasing US soybeans and grain. In the first quarter of this year, Vietnam experienced an 80 percent increase in registered foreign investments and 26 percent rise in exports to the United States (on a year-on-year basis) due to the US tariffs on China. According to UNCTAD, European companies can also expect to export about $70 billion more to both the US and China—replacing suppliers affected by tariffs.

On the other hand, countries and companies exporting capital goods and intermediate inputs to China would suffer due to a decline in demand. For example, South Korea has experienced four straight months of falling exports, in particular semiconductor exports to its biggest market—China. In addition, non-tariff barriers could disadvantage other third-country companies both before and after a trade agreement between the United States and China. In short, when the two largest economies comprising almost 40 percent of the world’s GDP engage in an economic war, the global economy suffers.

The Global Economy Torn in Two

More importantly, the US effort to restrict the flow of advanced products and technology to China, to reduce the use of Chinese 5G technology by boycotting the telecommunications giant Huawei, and generally to reverse and repatriate global supply chains could begin to fragment the global economy into US- and China-driven economic spheres, with potentially huge implications for sustained growth and prosperity for the world.

The international community needs to be much more concerned about the current situation and more active in finding a way to engage both governments. Washington and Beijing still have time to walk back from the brink.

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and a former executive managing director of the Institute of International Finance.

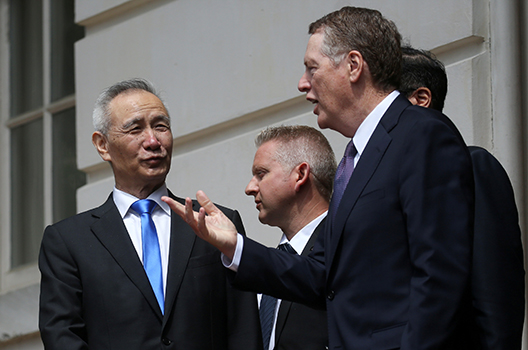

Image: China's Vice Premier Liu He listens to U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer as they exit the office of the U.S. Trade Representative following a second day of last ditch trade talks in Washington, U.S., May 10, 2019. (REUTERS/Leah Millis/File Photo)